(Press-News.org) New research from UVA Cancer Center could rescue once-promising immunotherapies for treating solid cancer tumors, such as ovarian, colon and triple-negative breast cancer, that ultimately failed in human clinical trials.

The research from Jogender Tushir-Singh, PhD, explains why the antibody approaches effectively killed cancer tumors in lab tests but proved ineffective in people. He found that the approaches had an unintended effect on the human immune system that potentially disabled the immune response they sought to enhance.

The new findings allowed Tushir-Singh to increase the approaches' effectiveness significantly in lab models, reducing tumor size and improving overall survival. The promising results suggest the renewed potential for the strategies in human patients, he and his team report.

"So far, researchers and protein engineers around the globe, including our research group, were focused on super-charging and super-activating tumor cell-death receptor targeting antibodies in the fight against cancer. Here at UVA, we took a comprehensive approach to harness the power of the immune system to create dual-specificity and potentially clinically effective oncologic therapeutics for solid tumors," said Tushir-Singh, of the UVA School of Medicine's Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics. "Our findings also have significant potential to improve further the clinical efficacy of currently FDA-approved PD-L1 targeting antibodies in solid tumors, particularly the ones approved for deadly triple-negative breast cancer."

Immunotherapy for Solid Tumors

Immunotherapy aims to harness the body's immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. Lab-engineered antibodies remain the core facilitator of immunotherapies and CAR T-cell therapies, which have generated tremendous excitement in the last decade. But these therapies have proved less effective against solid tumors than against melanoma (skin cancer) and leukemia (blood cancers). One major obstacle: It is difficult for immune cells to make their way efficiently into the core of solid tumors.

To overcome that problem, scientists have developed an approach that selectively uses antibodies to target a receptor on the cancer cells' surface called death receptor-5 (DR5). This approach essentially tells the cancer cells to die and enhances the permeation of the body's immune cells into a solid tumor. And it does so without the toxicity associated with chemotherapy.

Previously tested DR5-targeting antibodies have worked very well in lab tests and reduced tumor size in immune-deficient mouse models. But when tested in phase-II human clinical trials, these antibodies consistently failed to improve survival in patients - despite many big-name pharmaceutical companies spending billions of dollars on them.

Tushir-Singh, an antibody engineer, and his collaborators wanted to understand what was happening - why didn't this promising approach work in patients who need it desperately? They found that the anti-DR5 antibody approaches unintentionally triggered biological processes that suppress the body's immune response. This allowed the cancer tumors to evade the immune system and continue to grow.

Tushir-Singh and his team could restore the potency of the DR5-based antibody approach in human cancer cells and immune-sufficient mouse models by co-targeting the negative biological processes with improved, immune-activating therapy. The new combination therapy "markedly" increased the effectiveness of cancer killer immune cells known as T cells, shrinking tumors and improving survival in lab mice, they report in a new scientific paper.

That is an encouraging sign for the combination therapy's potential in patients with solid tumors, such as ovarian cancer and triple-negative breast cancer - the deadliest cancers in women.

"We would like to see these strategies in clinical trials, which we strongly believe have huge potential in solid tumors," Tushir-Singh said. "Our findings are extraordinary: Along with the translational impact, our work also explains, after more than 60 years of research in the field, why most approaches targeting apoptosis [cell death] have not done well in clinical trials and ultimately develop resistance to therapies."

INFORMATION:

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in the scientific journal EMBO Molecular Medicine. The research team consisted of Tanmoy Mondal, Gururaj N. Shivange, Rachisan G.T. Tihagam, Evan Lyerly, Michael Battista, Divpriya Talwar, Roxanna Mosavian, Karol Urbanek, Narmeen S. Rashid, J. Chuck Harrell, Paula D. Bos, Edward B. Stelow, M. Sharon Stack, Sanchita Bhatnagar and Tushir-Singh. UVA is seeking a patent based on the new combination approach.

The work was supported by National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health grant R01CA233752, U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (BCRP) breakthrough level 1 awards BC17097 and BC170197P1, Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program (OCRP) funding award OC180412 and a Cancer Center Support Grant, P30CA044579, to UVA.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at http://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

Seafood is a pillar of global food security--long recognized for its protein content. But research is highlighting a critical new link between the biodiversity of aquatic ecosystems and the micronutrient-rich seafood diets that help combat micronutrient deficiencies, or 'hidden hunger', in vulnerable populations.

"Getting the most nutritional value per gram of seafood is crucial in fighting hidden hunger and meeting United Nations Sustainable Development Goals," says Dr. Joey Bernhardt, an ecologist from the University of British Columbia (UBC) who led the study, published this week in the Proceedings of the National ...

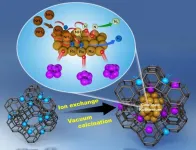

Nagoya University scientists in Japan have demonstrated how DNA-like molecules could have come together as a precursor to the origins of life. The findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, not only suggest how life might have begun, but also have implications for the development of artificial life and biotechnology applications.

"The RNA world is widely thought to be a stage in the origin of life," says Nagoya University biomolecular engineer Keiji Murayama. "Before this stage, the pre-RNA world may have been based on molecules called xeno nucleic acids ...

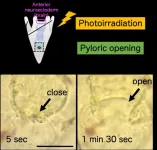

Tsukuba, Japan - Many life forms use light as an important biological signal, including animals with visual and non-visual systems. But now, researchers from Japan have found that neuronal cells may have initially evolved to regulate digestion according to light information.

In a study published this month in BMC Biology, researchers from the University of Tsukuba have revealed that sea urchins use light to regulate the opening and closing of the pylorus, which is an important component of the digestive tract.

Light-dependent systems often rely on the activity of proteins in the Opsin family, and these are found across the animal kingdom, including in organisms with visual and non-visual systems. Understanding ...

LOS ANGELES (April 5, 2021) -- New research from the Smidt Heart Institute shows that more patients--specifically those with medical risk factors or from underserved communities--opted into telehealth appointments for their cardiovascular care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data also suggests these telehealth patients underwent fewer diagnostic tests and received fewer medications than patients who saw their doctors in person.

The findings, published in JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association) Network Open, point to "digital shifts" in cardiovascular care amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

"We were encouraged to learn that access to cardiovascular ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Emily Ury remembers the first time she saw them. She was heading east from Columbia, North Carolina, on the flat, low-lying stretch of U.S. Highway 64 toward the Outer Banks. Sticking out of the marsh on one side of the road were not one but hundreds dead trees and stumps, the relic of a once-healthy forest that had been overrun by the inland creep of seawater.

"I was like, 'Whoa.' No leaves; no branches. The trees were literally just trunks. As far as the eye could see," said Ury, who recently earned a biology Ph.D. at Duke University working with professors Emily Bernhardt and Justin Wright.

In bottomlands throughout the U.S. East ...

Tsukuba, Japan - With a prevalence of about one in 10 people worldwide, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global health problem. It also often goes undetected, leading to a range of negative health outcomes, including death. Catching it at an early stage and adjusting nutrition and lifestyle can improve and extend life, but only if there are economically feasible systems in place to promote and educate on this.

Amid finite health-care resources, any CKD intervention must be both practical and cost-effective. A team of researchers centered at the University of Tsukuba now believe they have found a CKD behavioral intervention that can be delivered at a reasonable cost. They published their findings in the Journal of Renal Nutrition.

Changing eating and lifestyle habits, and ...

For the implementation of the effective hydrogen economy in the forthcoming years, hydrogen produced from sources like coal and petroleum must be transported from its production sites to the end user often over long distances and to achieve successful hydrogen trade between countries. Drs. Hyuntae Sohn and Changwon Yoon and their team at the Center for Hydrogen-fuel Cell Research of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) have announced a novel nanometal catalyst, constituting 60% less *ruthenium (Ru), an expensive precious metal used to extract hydrogen via ammonia decomposition.

*Ruthenium is a metal with the atomic number 44, and is a hard, expensive, silvery-white member of the platinum group of elements.

Ammonia has recently emerged as a liquid storage and transport ...

Epidemiological studies have found that transportation noise increases the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, with high-quality evidence for ischaemic heart disease. According to the WHO, ?1.6 million healthy life-years are lost annually from traffic-related noise in Western Europe. Traffic noise at night causes fragmentation and shortening of sleep, elevation of stress hormone levels, and increased oxidative stress in the vasculature and the brain. These factors can promote vascular dysfunction, inflammation and hypertension, thereby elevating the risk of cardiovascular ...

Humans have altered the ocean soundscape by drowning out natural noises relied upon by many marine animals, from shrimp to sharks.

Sound travels fast and far in water, and sea creatures use sound to communicate, navigate, hunt, hide and mate. Since the industrial revolution, humans have introduced their own underwater cacophony from shipping vessels, seismic surveys searching for oil and gas, sonar mapping of the ocean floor, coastal construction and wind farms. Global warming could further alter the ocean soundscape as the melting Arctic opens up more ...

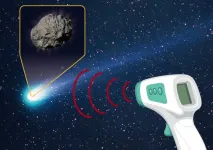

The world's first ground-based observations of the bare nucleus of a comet nearing the end of its active life revealed that the nucleus has a diameter of 800 meters and is covered with large grains of phyllosilicate; on Earth large grains of phyllosilicate are commonly available as talcum powder. This discovery provides clues to piece together the history of how this comet evolved into its current burnt-out state.

Comet nuclei are difficult to observe because when they enter the inner Solar System, where they are easy to observe from Earth, they heat up and release gas and dust which ...