(Press-News.org) The network of nerves connecting our eyes to our brains is sophisticated and researchers have now shown that it evolved much earlier than previously thought, thanks to an unexpected source: the gar fish.

Michigan State University's Ingo Braasch has helped an international research team show that this connection scheme was already present in ancient fish at least 450 million years ago. That makes it about 100 million years older than previously believed.

"It's the first time for me that one of our publications literally changes the textbook that I am teaching with," said Braasch, as assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology in the College of Natural Science.

This work, published in the journal Science on April 8, also means that this type of eye-brain connection predates animals living on land. The existing theory had been that this connection first evolved in terrestrial creatures and, from there, carried on into humans where scientists believe it helps with our depth perception and 3D vision.

And this work, which was led by researchers at France's Inserm public research organization, does more than reshape our understanding of the past. It also has implications for future health research.

Studying animal models is an invaluable way for researchers to learn about health and disease, but drawing connections to human conditions from these models can be challenging.

Zebrafish are a popular model animal, for example, but their eye-brain wiring is very distinct from a human's. In fact, that helps explain why scientists thought the human connection first evolved in four-limbed terrestrial creatures, or tetrapods.

"Modern fish, they don't have this type of eye-brain connection," Braasch said. "That's one of the reasons that people thought it was a new thing in tetrapods."

Braasch is one of the world's leading experts in a different type of fish known as gar. Gar have evolved more slowly than zebrafish, meaning gar are more similar to the last common ancestor shared by fish and humans. These similarities could make gar a powerful animal model for health studies, which is why Braasch and his team are working to better understand gar biology and genetics.

That, in turn, is why Inserm's researchers sought out Braasch for this study.

"Without his help, this project wouldn't have been possible," said Alain Chédotal, director of research at Inserm and a group leader of the Vision Institute in Paris. "We did not have access to spotted gar, a fish that does not exist in Europe and occupies a key position in the tree of life."

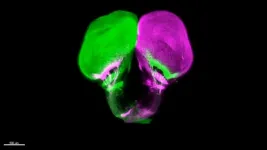

To do the study, Chédotal and his colleague, Filippo Del Bene, used a groundbreaking technique to see the nerves connecting eyes to brains in several different fish species. This included the well-studied zebrafish, but also rarer specimens such as Braasch's gar and Australian lungfish provided by a collaborator at the University of Queensland.

In a zebrafish, each eye has one nerve connecting it to the opposite side of the fish's brain. That is, one nerve connects the left eye to the brain's right hemisphere and another nerve connects its right eye to the left side of its brain.

The other, more "ancient" fish do things differently. They have what's called ipsilateral or bilateral visual projections. Here, each eye has two nerve connections, one going to either side of the brain, which is also what humans have.

Armed with an understanding of genetics and evolution, the team could look back in time to estimate when these bilateral projections first appeared. Looking forward, the team is excited to build on this work to better understand and explore the biology of visual systems.

"What we found in this study was just the tip of the iceberg," Chédotal said. "It was highly motivating to see Ingo's enthusiastic reaction and warm support when we presented him the first results. We can't wait to continue the project with him."

Both Braasch and Chédotal noted how powerful this study was thanks to a robust collaboration that allowed the team to examine so many different animals, which Braasch said is a growing trend in the field.

The study also reminded Braasch of another trend.

"We're finding more and more that many things that we thought evolved relatively late are actually very old," Braasch said, which actually makes him feel a little more connected to nature. "I learn something about myself when looking at these weird fish and understanding how old parts of our own bodies are. I'm excited to tell the story of eye evolution with a new twist this semester in our Comparative Anatomy class."

INFORMATION:

(Note for media: Please include a link to the original paper in online coverage: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe7790)

URBANA, Ill. - When scientists need to understand the effects of new infant formula ingredients on brain development, it's rarely possible for them to carry out initial safety studies with human subjects. After all, few parents are willing to hand over their newborns to test unproven ingredients.

Enter the domestic pig. Its brain and gut development are strikingly similar to human infants - much more so than traditional lab animals, rats and mice. And, like infants, young pigs can be scanned using clinically available equipment, including non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. That means researchers can test nutritional interventions in pigs, look at their effects on the developing brain via MRI, and make educated predictions about how those ...

Modern human-like brains evolved comparatively late in the genus Homo and long after the earliest humans first dispersed from Africa, according to a new study. By analyzing the impressions left behind by the ancient brains that once sat inside now fossilized skulls, the authors discovered that the brains of the earliest Homo retained a primitive, great ape-like organization of the frontal lobe. The findings challenge the long-standing assumption that human-like brain organization is a hallmark of early Homo and suggest that the evolutionary history of the human brain is more complex than previously thought. Our modern brains are larger and structurally different than those of our closest living relatives, ...

Researchers present a new, low-temperature method for injection-molding transparent fused silica glass, similar to how many plastic objects are manufactured. According to the authors, the process offers the possibility of producing complex and high-quality glass components using the same fabrication methods that allowed polymers to become one of the most important materials of the 21st century. The optical, thermal, mechanical and chemical properties of silicate glasses make them an ideal non-carbon based, high-performance material with applications ranging from packaging and architecture to high-throughput fiber optic ...

Using a novel genetic editing system termed intMEMOIR, researchers reveal the cell lineage histories of individual cells within their native tissue context, according to a new study. The new approach provides a powerful new tool for recording cell lineage in diverse cellular systems. During multicellular development, a cell's spatial position and lineage play important roles in cell fate determination. The ability to visualize lineage relationships directly within their native tissues can provide valuable insight into the factors that affect development and disease. This promise has spurred the development of several ...

X-ray emissions from the Crab Pulsar are more intense during giant radio pulses (GRPs), researchers report. The new findings provide constraints on the mechanisms underlying GRPs and may provide insights into other transient radio phenomena observed throughout the Universe. Pulsars, or rapidly spinning neutron stars, emit pulses of electromagnetic radiation from their magnetospheres and are observed from Earth as regular sequences of radio pulses. Most radio pulses from these distant objects are of a consistent intensity. Occasionally, however, sporadic and short-lived ...

The functioning of the enzyme FAP, useful for producing biofuels and for green chemistry, has been decrypted. This result mobilized an international team of scientists, including many French researchers from the CEA, CNRS, Inserm, École Polytechnique, the universities of Grenoble Alpes, Paris-Saclay and Aix Marseille, as well as the European Synchrotron (ESRF) and synchrotron SOLEIL. The study is published in Science on April 09, 2021.

The researchers decrypted the operating mechanisms of FAP (Fatty Acid Photodecarboxylase), which is naturally present in microscopic algae such as Chlorella. The enzyme had been identified in 2017 as able to use light energy to form hydrocarbons from fatty acids ...

Two studies published in the open-access journal PLOS Pathogens provide new evidence supporting an important role for the immune system in shaping the evolution of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. These findings--and the novel technology behind them--improve understanding of how new SARS-CoV-2 strains arise, which could help guide treatment and vaccination efforts.

For the first study, Rachel Eguia of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and colleagues sought to better understand SARS-CoV-2 by investigating a closely related virus that has circulated widely for a far longer period of time: the common-cold virus ...

A group led by scientists from the RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research, using coordinated observations of the Crab pulsar in a number of frequencies, have discovered that the "giant radio pulses" which it emits include an increase in x-ray emissions in addition to the radio and visible light emissions that had been previously observed. This finding, published in Science, implies that these pulses are hundreds of times more energetic than previously believed and could provide insights into the mysterious phenomenon of "fast radio bursts (FRBs)."

Giant radio pulses--a phenomenon where extremely short, millisecond-duration pulses of radio waves are emitted--have ...

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute have found that blocking a specific protein could increase tumour sensitivity to treatment with PARP inhibitors. Their work published in Science , suggests combining treatments could lead to improved therapy for patients with inheritable breast cancers.

Some cancers, including certain breast, ovarian and prostate tumours, are caused by a fault in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, which are important for DNA repair. Treatment for these cancers has greatly improved thanks to the discovery of PARP inhibitors, drugs which capitalise on this weakness in the cancer ...

Scientists at the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute in Sydney have discovered a critical new gene that it is hoped could help human hearts repair damaged heart muscle after a heart attack.

Researchers have identified a genetic switch in zebrafish that turns on cells allowing them to divide and multiply after a heart attack, resulting in the complete regeneration and healing of damaged heart muscle in these fish.

It's already known that zebrafish can heal their own hearts, but how they performed this incredible feat remained unknown, until now. In research recently published in the prestigious journal, Science, the team at the Institute drilled down into a critical ...