(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON--Deep in a Jamaican cave is a treasure trove of bat poop, deposited in sequential layers by generations of bats over 4,300 years.

Analogous to records of the past found in layers of lake mud and Antarctic ice, the guano pile is roughly the height of a tall man (2 meters), largely undisturbed, and holds information about changes in climate and how the bats' food sources shifted over the millennia, according to a new study.

"We study natural archives and reconstruct natural histories, mostly from lake sediments. This is the first time scientists have interpreted past bat diets, to our knowledge," said Jules Blais, a limnologist at the University of Ottawa and an author of the new study in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, AGU's journal for research on the interactions among biological, geological and chemical processes across Earth's ecosystems.

Blais and his colleagues applied the same techniques used for lake sediments to a guano deposit found in Home Away from Home Cave, Jamaica, extracting a vertical "core" extending from the top of the pile to the oldest deposits at the bottom and taking it to the lab for biochemical analysis.

About 5,000 bats from five species currently use the cave as daytime shelter, according to the researchers.

"Like we see worldwide in lake sediments, the guano deposit was recording history in clear layers. It wasn't all mixed up," Blais said. "It's a huge, continuous deposit, with radiocarbon dates going back 4,300 years in the oldest bottom layers."

The new study looked at biochemical markers of diet called sterols, a family of sturdy chemicals made by plant and animal cells that are part of the food bats and other animals eat. Cholesterol, for example, is a well-known sterol made by animals. Plants make their own distinctive sterols. These sterol markers pass though the digestive system into excrement and can be preserved for thousands of years.

"As a piece of work showing what you can do with poo, this study breaks new ground," said Michael Bird, a researcher in environmental change in the tropics at James Cook University in Queensland, Australia, who was not involved in the new study. "They really extended the toolkit that can be used on guano deposits around the world."

Past climates, past diets

Like sediment and ice core records, the guano core extracted from the Jamaican cave recorded the chemical signatures of human activities like nuclear testing and leaded gasoline combustion, which, along with radiocarbon dating, helped the researchers to correlate the history seen in the guano with other events in Earth's climate history.

Bats pollinate plants, suppress insects and spread seeds while foraging for food. Shifts in bat diet or species representation in response to climate can have reverberating effects on ecosystems and agricultural systems.

"We inferred from our results that past climate has had an effect on the bats. Given the current changes in climate, we expect to see changes in how bats interact with the environment," said Lauren Gallant, a researcher at the University of Ottawa and an author of the new study. "That could have consequences for ecosystems."

The new study compared the relative amounts of plant and animal sterols in the guano core moving back in time though the layers of guano to learn about how bat species as a group shifted their exploitation of different food sources in the past.

The research team, which included bat biologists and a local caving expert, also followed living bats in Belize, tracking their food consumption and elimination to gain a baseline for the kinds of sterols that pass through to the poop when bats dine on different food groups.

Plant sterols spiked compared to animal sterols about 1,000 years ago during the Medieval Warm Period (900-1,300 CE), the new study found, a time when cores of lakebed sediments in Central America suggest the climate in the Americas was unusually dry. A similar spike occurred 3,000 years ago, at a time known as the Minoan Warm Period (1350 BCE).

"Drier conditions tend to be bad for insects," Blais said. "We surmised that fruit diets were favored during dry periods."

The study also found changes in the carbon composition of the guano that likely reflect the arrival of sugarcane in Jamaica in the fifteenth century.

"It's remarkable they can find biochemical markers that still contain information 4,000 years later," Bird said. "In the tropics, everything breaks down fast."

The approach demonstrated in the new study could be used to glean ecological information from guano deposits around the world, even those only a few hundred years old, Bird said.

"Quite often there are no lakes around, and the guano provides a good option for information about the past. It also contains biological information that lakes don't." Bird said. "There's a lot more work to do and a lot more caves out there."

INFORMATION:

AGU (http://www.agu.org) supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists:

This research study will be free available for 30 days. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

"A 4,300 year history of dietary changes in a bat colony determined from a tropical guano deposit"

Authors:

Lauren Gallant (University of Ottawa, Canada)

MB Fenton (University of Western Ontario, Canada)

Chris Grooms (Queens University, Canada)

Wieslaw Bogdanowicz (Museum and Institute of Zoology, Poland)

RS Stewart (Jamaican Caves Organization, Ewarton, Jamaica)

Elizabeth Clare (Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom)

John Smol (Queens University, Canada)

Jules Blais, corresponding author (University of Ottawa, Canada) END

BOSTON - Exercise training may slow tumor growth and improve outcomes for females with breast cancer - especially those treated with immunotherapy drugs - by stimulating naturally occurring immune mechanisms, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard Medical School (HMS) have found.

Tumors in mouse models of human breast cancer grew more slowly in mice put through their paces in a structured aerobic exercise program than in sedentary mice, and the tumors in exercised mice exhibited an increased anti-tumor immune response.

"The most exciting finding was that exercise training brought into tumors immune cells capable of killing cancer cells known as cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+ ...

Philadelphia, April 12, 2021 - Electronic cigarette (EC) use, or vaping, has both gained incredible popularity and generated tremendous controversy, but although they may be less harmful than tobacco cigarettes (TCs), they have major potential risks that may be underestimated by health authorities, the public, and medical professionals. Two cardiovascular specialists review the latest scientific studies on the cardiovascular effects of cigarette smoking versus ECs in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology, published by Elsevier. They conclude that young non-smokers should be discouraged from vaping, flavors targeted towards adolescents should be banned, and laws and regulations ...

What exactly happens when the corona virus SARS-CoV-2 infects a cell? In an article published in Nature, a team from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry paints a comprehensive picture of the viral infection process. For the first time, the interaction between the coronavirus and a cell is documented at five distinct proteomics levels during viral infection. This knowledge will help to gain a better understanding of the virus and find potential starting points for therapies.

When a virus enters a cell, viral and cellular protein molecules begin to interact. Both the replication of the virus and the reaction of ...

PHILADELPHIA - Residents in majority-Black neighborhoods experience higher rates of severe pregnancy-related health problems than those living in predominantly-white areas, according to a new study of pregnancies at a Philadelphia-based health system, which was led by researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The findings, published today in Obstetrics and Gynecology, suggest that neighborhood-level public health interventions may be necessary in order to lower the rates of severe maternal morbidity -- such as a heart attack, heart failure, eclampsia, or hysterectomy -- and mortality ...

April 12, 2021 - For critically ill COVID-19 patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), the risk of death remains high - but is much lower than suggested by initial studies, according to a report published today by Annals of Surgery. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The findings support the use of ECMO as "salvage therapy" for COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or respiratory failure who do not improve with conventional mechanical ventilatory support, according to the new research by Ninh T. Nguyen, MD, Chair of the Department of Surgery, University ...

New research by Yale Cancer Center shows patients with early-onset colorectal cancer, age 50 and younger, have a better survival rate than patients diagnosed with the disease later in life. The study was presented virtually today at the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting.

"Although small, we were surprised by our findings," said En Cheng, MD, MSPH, lead author of the study from Yale Cancer Center. "Past studies have shown younger colorectal patients, those under 50, were reported to experience worse survival compared with patients diagnosed at older ages. We hope this result can be inspiring for these ...

In a new study led by Yale Cancer Center, researchers have advanced a tumor-targeting and cell penetrating antibody that can deliver payloads to stimulate an immune response to help treat melanoma. The study was presented today at the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) virtual annual meeting.

"Most approaches rely on direct injection into tumors of ribonucleic acids (RNAs) or other molecules to boost the immune response, but this is not practical in the clinic, especially for patients with advanced cancer," said Peter M. Glazer, MD, PhD, Chair of the Department of Therapeutic Radiology ...

New research from CU Cancer Center member Scott Cramer, PhD, and his colleagues could help in the treatment of men with certain aggressive types of prostate cancer.

Published this week in the journal Molecular Cancer Research, Cramer's study specifically looks at how the loss of two specific prostate tumor-suppressing genes -- MAP3K7 and CHD1 --increases androgen receptor signaling and makes the patient more resistant to the anti-androgen therapy that is typically administered to reduce testosterone levels in prostate cancer patients.

"Doctors don't normally stratify patients based on this subtype and say, 'We're going to have to treat these people differently,' but we think this should be considered before treating ...

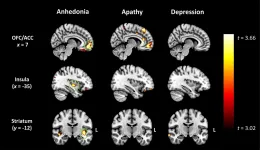

KEY POINTS:

- Loss of pleasure has been revealed as a key feature in early-onset dementia (FTD), in contrast to Alzheimer's disease.

- Scans showed grey matter deterioration in the so-called pleasure system of the brain.

- These regions were distinct from those implicated in depression or apathy - suggesting a possible treatment target.

People with early-onset dementia are often mistaken for having depression and now Australian research has discovered the cause: a profound loss of ability to experience pleasure - for example a delicious meal or beautiful sunset - related to degeneration of 'hedonic hotspots' in the brain where pleasure mechanisms are concentrated.

The University of Sydney-led ...

While the new Coronavirus will, hopefully, be effectively controlled sooner rather than later, its latest namesake is here to stay - a small caddisfly endemic to a national park in Kosovo that is new to science.

Potamophylax coronavirus was collected near a stream in the Bjeshkët e Nemuna National Park in Kosovo by a team of scientists, led by Professor Halil Ibrahimi of the University of Prishtina. After molecular and morphological analyses, it was described as a caddisfly species, new to science in the open-access, peer-reviewed Biodiversity Data Journal.

Ironically, the study of this new insect was impacted by the same pandemic that inspired its scientific name. Although it was collected a few years ago, the new species was only described during the global pandemic, ...