Better treatment for aggressive prostate cancer

The CU Cancer Center's Scott Cramer, PhD, is studying how the deletion of tumor-suppressing genes makes patients resistant to traditional treatments.

2021-04-12

(Press-News.org) New research from CU Cancer Center member Scott Cramer, PhD, and his colleagues could help in the treatment of men with certain aggressive types of prostate cancer.

Published this week in the journal Molecular Cancer Research, Cramer's study specifically looks at how the loss of two specific prostate tumor-suppressing genes -- MAP3K7 and CHD1 --increases androgen receptor signaling and makes the patient more resistant to the anti-androgen therapy that is typically administered to reduce testosterone levels in prostate cancer patients.

"Doctors don't normally stratify patients based on this subtype and say, 'We're going to have to treat these people differently,' but we think this should be considered before treating them with anti-androgen therapy because they appear to be already inherently resistant to the therapy," says Cramer, professor in the Department of Pharmacology. "They're less likely to respond to the treatment."

Cramer was the corresponding author on the paper. Lauren Jillson, a graduate student in the Cancer Biology Graduate Program at CU Anschutz, was the lead author on the study. Other CU Cancer Center members included M. Scott Lucia, MD, and James Costello, PhD. The 11 other authors were a mix of CU School of Medicine Department of Pharmacology and Department of Pathology researchers, as well as Stanford University and University of California researchers.

Elsewhere in the paper, Cramer and his co-researchers show that the loss of the expression of the MAP3K7 gene, in particular, is associated with poor outcomes, making it even more vital to treat patients who show the loss of the gene. Cramer notes that the majority of men diagnosed with prostate cancer have slow-growing tumors that are at low risk for metastasis, but about 20% of patients will eventually develop aggressive metastatic disease. Knowing that the lack of MAP3K7 and CHD1 is a signal of a more aggressive disease, and that treatments such as surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy all have side effects that can be significant, Cramer hopes eventually doctors can use the deletion as a marker for men who would benefit most from aggressive treatment strategies and spare those who are less likely to succumb to their disease.

"Those patients should be treated more aggressively than other patients because they're more likely to die from the disease," he says. "And we know that 50% of patients with loss of MAP3K7 and CHD1 are likely to recur after their primary treatment with recurrent disease."

An earlier study by Cramer showed that of prostate cancer patients with combination MAP3K7 and CHD1 deletions, about half will have recurrent prostate cancer, which ultimately leads to death. About 10-15% of all prostate cancers harbor combined MAP3K7-CHD1 deletions. He and his team are now investigating alternative treatment methods for patients resistant to anti-androgen therapy due to the deletions.

"Our ultimate goal is better treatment," he says. "There is a lot more work that needs to be done to reproduce our findings, validate them, and then extend them into preclinical models. If those all look good, then patients could potentially be stratified based on their expression of these proteins, and then hopefully we'll have better ways to treat them."

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-12

KEY POINTS:

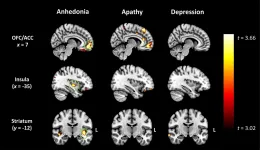

- Loss of pleasure has been revealed as a key feature in early-onset dementia (FTD), in contrast to Alzheimer's disease.

- Scans showed grey matter deterioration in the so-called pleasure system of the brain.

- These regions were distinct from those implicated in depression or apathy - suggesting a possible treatment target.

People with early-onset dementia are often mistaken for having depression and now Australian research has discovered the cause: a profound loss of ability to experience pleasure - for example a delicious meal or beautiful sunset - related to degeneration of 'hedonic hotspots' in the brain where pleasure mechanisms are concentrated.

The University of Sydney-led ...

2021-04-12

While the new Coronavirus will, hopefully, be effectively controlled sooner rather than later, its latest namesake is here to stay - a small caddisfly endemic to a national park in Kosovo that is new to science.

Potamophylax coronavirus was collected near a stream in the Bjeshkët e Nemuna National Park in Kosovo by a team of scientists, led by Professor Halil Ibrahimi of the University of Prishtina. After molecular and morphological analyses, it was described as a caddisfly species, new to science in the open-access, peer-reviewed Biodiversity Data Journal.

Ironically, the study of this new insect was impacted by the same pandemic that inspired its scientific name. Although it was collected a few years ago, the new species was only described during the global pandemic, ...

2021-04-12

New research shows that people who experience big dips in blood sugar levels, several hours after eating, end up feeling hungrier and consuming hundreds more calories during the day than others.

A study published today in Nature Metabolism, from PREDICT, the largest ongoing nutritional research program in the world that looks at responses to food in real life settings, the research team from King's College London and health science company ZOE (including scientists from Harvard Medical School, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Nottingham, Leeds University, and Lund University ...

2021-04-12

Between 2018 and 2020, 1,4 million EU citizens signed the petition 'End the Cage Age', with the aim of ending cage housing for farm animals in Europe. In response to this citizens initiative, the European Parliament requested a study by Utrecht University researchers on the possibilities to end cage housing. On 13 April, the scientists will present their report 'End the Cage Age - Looking for Alternatives' to the European Parliament.

In the report, behavioural biologists, animal scientists, veterinarians and ethicists from Utrecht University's Faculty of Veterinary Medicine analysed the available scientific literature on alternatives to cage housing. "Our focus was on laying hens and pigs" says Bas Rodenburg, Professor of Animal Welfare at Utrecht University. "Because these ...

2021-04-12

Many women "risk" allowing natural grey hair to show in order to feel authentic, a new study shows.

Researchers from the University of Exeter surveyed women who chose not to dye their grey hair, and found a "conflict" between looking natural and being seen as competent.

Participants in the study - mostly from English-speaking countries - belonged to online groups whose members allow their natural grey hair to show, and the researchers noted "solidarity and sisterhood" among these women.

"We are all constrained by society's norms and expectations when it comes to appearance, but expectations are more rigorous for women - especially older women," said lead author Vanessa Cecil, of the University of Exeter.

"The 'old woman' is an undesirable character in Western societies, being seen ...

2021-04-12

Why is sugar not transparent? Because light that penetrates a piece of sugar is scattered, altered and deflected in a highly complicated way. However, as a research team from TU Wien (Vienna) and Utrecht University (Netherlands) has now been able to show, there is a class of very special light waves for which this does not apply: for any specific disordered medium--such as the sugar cube you may just have put in your coffee--tailor-made light beams can be constructed that are practically not changed by this medium, but only attenuated. The light beam penetrates the medium, and a light pattern arrives on the other ...

2021-04-12

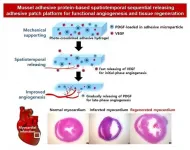

Blood vessels deliver nutrients and oxygen to each organ in our body. They are difficult to completely restore to their original conditions once damaged by myocardial infarction or severe ischemic diseases. This is because various angiogenic growth factors must be applied sequentially in order to restore the vascular structure. Recently, a research team at POSTECH has bioengineered a novel adhesive patch platform that can efficiently deliver blood vessel-forming growth factors spatiotemporally using mussel adhesive protein (MAP), a bio-adhesive material that is made from mussels harmless to humans.

A POSTECH research team led by Professor Hyung Joon ...

2021-04-12

Squirrels and other tree-dwelling rodents evolved to have bigger brains than their burrowing cousins, a study suggests.

This greater brain power has given them key abilities needed to thrive in woodland habitats, including better vision and motor skills, and improved head and eye movements, researchers say.

Scientists have shed light on how the brains of rodents - a diverse group that accounts for more than 40 per cent of all mammals - have changed since they evolved around 50 million years ago.

Few studies looking into factors affecting brain size in mammals have taken account ...

2021-04-12

New Orleans, LA - A study led by Hui-Yi Lin, Ph.D., Professor of Biostatistics, and a team of researchers at LSU Health New Orleans Schools of Public Health and Medicine has found that adequate levels of five antioxidants may reduce infection with the strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV) associated with cervical cancer development. Findings are published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Although previous studies have suggested that the onset of HPV-related cancer development may be activated by oxidative stress, the association had not been clearly understood. This study evaluated associations between 15 antioxidants and vaginal HPV infection status -- no, low-risk, and oncogenic/high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) -- in 11,070 women aged 18-59 who participated ...

2021-04-12

In 2018, Pompeu Fabra University launched its Planetary Wellbeing initiative, a long-term institutional strategy spurred by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and based on the Planetary Health project promoted by the Rockefeller Foundation and The Lancet.

Fifteen academics and public officials, led by the three directors of the initiative, Josep Maria Antó, scientific director of ISGlobal; Josep Lluís Martí, UPF vice-rector for innovation projects, and Jaume Casals, UPF rector, are the authors of an academic article published in the journal ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Better treatment for aggressive prostate cancer

The CU Cancer Center's Scott Cramer, PhD, is studying how the deletion of tumor-suppressing genes makes patients resistant to traditional treatments.