(Press-News.org) In a series of experiments that began with amoebas -- single-celled organisms that extend podlike appendages to move around -- Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists say they have identified a genetic pathway that could be activated to help sweep out mucus from the lungs of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease a widespread lung ailment.

"Physician-scientists and fundamental biologists worked together to understand a problem at the root of a major human illness, and the problem, as often happens, relates to the core biology of cells," says Doug Robinson, Ph.D., professor of cell biology, pharmacology and molecular sciences, medicine (pulmonary division), oncology, and chemical and biomedical engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of death in the U.S., affecting more the 15 million adults, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The disease causes the lungs to fill up with mucus and phlegm, and people with COPD experience chronic cough, wheezing and difficulty breathing. Cigarette smoking is the main cause in as many as three-quarters of COPD cases, and there is no cure or effective treatment available despite decades of research.

In a report on their new work, published Feb. 25 in the Journal of Cell Science, the researchers say they took a new approach to understanding the biology of the disorder by focusing on an organism with a much simpler biological structure than human cells to identify genes that might protect against the damaging chemicals in cigarette smoke.

Robinson and his collaborator, Ramana Sidhaye, M.D., also a professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonology at Johns Hopkins, with their former lab member Corrine Kliment, M.D., Ph.D., counted on the knowledge that as species evolved, genetic pathways were frequently retained across the animal kingdom.

Enter the soil-dwelling amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, which has long been studied to understand cell movement and communication. The scientists pumped lab-grade cigarette smoke through a tube and bubbled it into the liquid nutrients bathing the amoeba. Then, the scientists used engineered amoeba to identify genes that could provide protection against the smoke.

Looking at the genes that provided protection, creating "survivor" cells, one family of genes stood out among the rest: adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT). Proteins made by this group of genes are found in the membrane, or surface, of a cell's energy powerhouse structure, known as mitochondria. Typically, mitochondria help make the fuel that cells use to survive. When an ANT gene is highly active, cells get better at making fuel, protecting them from the smoke.

Kliment, Robinson and the team suspected they also help amoeba overcome the damaging effects of cigarette smoke.

To better understand how ANT genes behave in humans, the scientists studied tissue samples of cells lining the lungs taken from 28 people with COPD who were treated at the University of Pittsburgh and compared the lung cells' genetic activity with cells from 20 people with normal lung function.

The scientists found that COPD patients had about 20% less genetic expression of the ANT2 gene than those with normal lung function. They also found that mice exposed to smoke lose ANT2 gene expression.

Next, Robinson, Kliment and their research team sought to discover how ANT2 might provide protection from cigarette smoke chemicals and, in the process, discovered something completely unexpected.

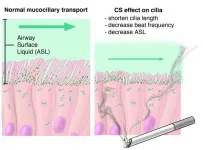

Cells lining the lungs use fingerlike projections called cilia to sweep mucus and other particles out of the lungs. In mammals, including people, the scientists found that the ANT2 gene produces proteins that localize in and around the cilia that work to release tiny amounts of the cell's fuel into a watery substance next to the cell. The fuel enhances the ability of the cilia to "beat" rhythmically and regularly to sweep away the mucus.

"In COPD patients, mucus becomes too thick to sweep out of the lungs," says Robinson.

The Johns Hopkins Medicine team found that, compared with human lung cells with normal ANT2 function, cilia in human lung cells lacking ANT2 beat 35% less effectively when exposed to smoke. In addition, the watery liquid next to the cell was about half the height of normal cells, suggesting the liquid was denser, which can also contribute to lower beat rates.

When the scientists genetically engineered the lung cells to have an overactive ANT2 gene and exposed them to smoke, the cells' cilia beat with the same intensity as normal cells not exposed to smoke. The watery layer next to these cells was about 2.5 times taller than that of cells lacking ANT2.

"Cells are good at repurposing cellular processes across species, and in our experiments, we found that mammals have repurposed the ANT gene to help deliver cellular cues to build the appropriate hydration layer in airways," says Robinson. "Who would have thought that a mitochondrial protein could also live at the cell surface and be responsible for helping airway cilia beat and move?"

Robinson says that further research may yield discoveries to develop gene therapy or drugs to add ANT2 function back into lung-lining cells as a potential treatment for COPD.

INFORMATION:

Robinson is now working to start a biotechnology company to further develop the technology. Kliment is continuing the work in her new laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh, where she is now an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine.

Other scientists who contributed to the research include Jennifer Nguyen, YaWen Lu, Steven Claypool, and Pablo Iglesias from Johns Hopkins, and Mary Jane Kaltreider, Josiah Radder, Frank Sciurba, Yingze Zhang, and Alyssa Gregory from the University of Pittsburgh.

Funding for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health's National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (F32HL129660, K08HL141595, R01HL124099, R01HL108882); National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM66817); a Biochemistry, Cellular, and Molecular Biology Program Training Grant (T32GM007445); the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; Parker B Francis Pulmonary Fellowship; the Johns Hopkins Bauernschmidt Fellowship Foundation; the Thomas Wilson Foundation; the American Heart Association; the Airway Cell and Tissue Core; the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

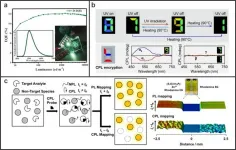

Circularly polarized light exhibits promising applications in future displays and photonic technologies. Traditionally, circularly polarized light is converted from unpolarized light by the linear polarizer and the quarter-wave plate. During this indirectly physical process, at least 50% of energy will be lost. Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) from chiral luminophores provides an ideal approach to directly generate circularly polarized light, in which the energy loss induced by polarized filter can be reduced. Among various chiral luminophores, organic micro-/nano-structures have attracted increasing attention owing to the high quantum efficiency ...

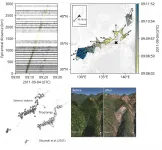

Tsukuba, Japan - Tropical cyclones like typhoons may invoke imagery of violent winds and storm surges flooding coastal areas, but with the heavy rainfall these storms may bring, another major hazard they can cause is landslides--sometimes a whole series of landslides across an affected area over a short time. Detecting these landslides is often difficult during the hazardous weather conditions that trigger them. New methods to rapidly detect and respond to these events can help mitigate their harm, as well as better understand the physical processes themselves.

In a new study published in Geophysical Journal International, a research team led ...

Hokkaido University researchers have clarified different causes of past glacial river floods in the far north of Greenland, and what it means for the region's residents as the climate changes.

The river flowing from the Qaanaaq Glacier in northwest Greenland flooded in 2015 and 2016, washing out the only road connecting the small village of Qaanaaq and its 600 residents to the local airport. What caused the floods was unclear at the time. Now, by combining physical field measurements and meteorological data into a numerical model, researchers at Japan's Hokkaido ...

The semiconductor industry and pretty much all of electronics today are dominated by silicon. In transistors, computer chips, and solar cells, silicon has been a standard component for decades. But all this may change soon, with gallium nitride (GaN) emerging as a powerful, even superior, alternative. While not very heard of, GaN semiconductors have been in the electronics market since 1990s and are often employed in power electronic devices due to their relatively larger bandgap than silicon--an aspect that makes it a better candidate for high-voltage and high-temperature applications. Moreover, current travels quicker through GaN, which ensures fewer switching losses during switching applications.

Not everything about GaN is perfect, however. While impurities are usually desirable ...

People who have recovered from COVID-19, especially those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, may be at risk of developing blood clots due to a lingering and overactive immune response, according to a study led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU) scientists.

The team of researchers, led by NTU Assistant Professor Christine Cheung, investigated the possible link between COVID-19 and an increased risk of blood clot formation, shedding new light on "long-haul COVID" - the name given to the medium- and long-term health consequences of COVID-19.

The findings may help to explain why some people who have recovered from COVID-19 exhibit symptoms of blood clotting complications after their initial recovery. In some cases, they are at increased risk of heart attack, ...

Evolutionary anthropologists from the University of Vienna and colleagues now present evidence for a different explanation, published in PNAS. A larger bony pelvic canal is disadvantageous for the pelvic floor's ability to support the fetus and the inner organs and predisposes to incontinence.

The human pelvis is simultaneously subject to obstetric selection, favoring a more spacious birth canal, and an opposing selective force that favors a smaller pelvic canal. Previous work of scientists from the University of Vienna has already led to a relatively good understanding of this evolutionary "trade-off" and how it results in the high rates of obstructed labor in modern humans. ...

They are diligently stoking thousands of bonfires on the ground close to their crops, but the French winemakers are fighting a losing battle. An above-average warm spell at the end of March has been followed by days of extreme frost, destroying the vines with losses amounting to 90 percent above average. The image of the struggle may well be the most depressingly beautiful illustration of the complexities and unpredictability of global climate warming. It is also an agricultural disaster from Bordeaux to Champagne.

It is the loss of the Arctic sea-ice due to climate warming that has, somewhat paradoxically, been implicated with severe cold and snowy mid-latitude winters.

"Climate change doesn't always manifest in the most ...

Altering a mosquito's gut genes to make them spread antimalarial genes to the next generation of their species shows promise as an approach to curb malaria, suggests a preliminary study published today in eLife.

The study is the latest in a series of steps toward using CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology to make changes in mosquito genes that could reduce their ability to spread malaria. If further studies support this approach, it could provide a new way to reduce illnesses and deaths caused by malaria.

Growing mosquito resistance to pesticides, as well as malaria parasite resistance ...

Many consumers are willing to pay for improved environmental quality and thus non-market values of impacts of food production on e.g. water quality, C sequestration, biodiversity, pollution, erosion or GHG emissions may even be comparable to the market value of agricultural production. Diverfarming project elucidated how consumers value agroecosystem services enabled by diversification and provided consumer perspectives for developing future agricultural and food policies to better support cropping diversification.

The researchers quantified consumers' willingness to pay for the benefits of increased farm and regional scale diversity of cultivation practices and crop rotations. Three valuation scenarios were presented to a ...

Spain boasts the largest cultivated area of almond trees in the world, with more than 700,000 ha (MAPA, 2018), but ranks third in terms of production. How can this be? Actually it's easy to explain: most of the country's cultivated area of almond trees is comprised of traditional rainfed orchards and located in marginal areas featuring a low density of trees per hectare.

Over the last decade, however, the nut's surging prices havegiven rise to intensive almond tree plantations characterised bya high density of trees per hectare and the employment offertilisation and irrigation, yielding endless rows of white when the trees are in bloom. Knowing what the future of these plantations will be like in a ...