Experimental and computational biologists at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) have teamed up to establish an approach to induce thousands of different mutations in up to 1 million microscopic worms and analyze the resulting effects on the worms' physical traits and functions.

"With cell lines, you are missing development processes, many cell-types, as well as interaction between cell types that all affect gene regulation," says Jonathan Froehlich, a Ph.D. candidate in MDC's Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements Lab in the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB) and co-first paper author. "We can now really test these regulatory sequences in the environment where they are important and observe the consequences on the organism."

Worms meet CRISPR-Cas9

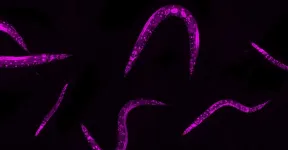

The tiny Caenorhabditis elegans worms are an excellent proxy for investigating gene regulation processes in humans. "We are so similar to them," Froehlich says. "They have specialized tissues, they have muscles, they have nerves, they have skin, they have a gut, a reproductive system. For gene regulation studies, it's important that you have specialized cell types and development."

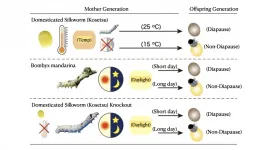

To efficiently induce a variety of mutations in a large C. elegans population, the researchers turned to the gene editing tool, CRISPR-Cas9. They identified up to 10 sections of DNA to be cut by the Cas9 enzyme, which is guided to those spots by RNA. But the researchers didn't send in any other instructions, leaving the organisms to repair the DNA breaks through natural mechanisms. This leads to a variety of mutations in the form of deletions or insertions of genetic code, which are called "indels."

Rolling the dice

Often in the realm of genome editing, scientists want to be very precise to see how one mutation will affect a system. Not so in this experimental set up, which aims to look at a variety of mutations all at once.

"One part is controlled, the part where we design the guide RNAs and tell the Cas9 nuclease where to go, but the outcome of this is semi-random," says Froehlich. "You will have many different types of outcomes and we can see what the effect is on the animal."

Notably, the researchers only needed to manipulate a parent generation of C. elegans. They added the Cas9 system to the parents; when the worms were exposed to heat for two hours the enzyme went to work cutting the DNA in reproductive germline cells. Then the hermaphrodite worms reproduced, resulting in thousands of offspring containing a variety of mutations. No need to modify the genomes of worms one by one.

crispr-DART

To identify the resulting mutations in hundreds of thousands of worms, the team used a wide variety of genomic sequencing techniques, producing a huge volume of data. To efficiently analyze it, they teamed up with MDC's Bioinformatics & Omics Data Science Platform.

Dr. Bora Uyar, a bioinformatics scientist, first looked for existing tools that could help answer necessary questions, such as: was the Cas9 system activated, were the targeted areas of DNA cut, and which sequences are important for genome function? "I tried the tools that existed and none were designed to address these problems with such a wide variety of data types and large number of mutations, and produce the interactive data visualizations we ultimately wanted," Uyar says.

So, he set to work designing a new software package, called crispr-DART - short for Downstream Analysis and Reporting Tool. It is an homage to the parallel editing approach, which is not 100% controlled and so doesn't always lead to mutations in the target areas. "That's why I call it crispr-DART, you are throwing some arrows in the genome and the tool tells you if you are actually successful or not," Uyar says.

The software, which is publicly available, can handle a variety of different sequencing data types - long read, short read, single reads, paired reads, DNA, RNA. The system quickly processes the samples, even as new types of information are added to the mix, helping identify interesting findings, such as the efficiency of the protocol and how mutations compare to controls.

"crispr-DART follows the principles we use in our other pipelines, where reproducibility, usability and informative reporting are very important components," says Dr. Altuna Akalin, who heads MDC's Bioinformatics & Omics Data Science Platform.

Surprise finding

Using the new protocol, the team was able to connect several mutations in regulatory regions to specific physiological effects. They also made an unexpected finding. Two microRNA binding sites in a gene called lin-41 have long been thought to work together to control gene expression. With their parallel editing system, the team induced mutations in one or the other site, and then in both sites together. As long as one site was intact, the worms developed normally. But if both sites were mutated, gene expression continued unregulated, the worms did not develop normally and died.

"This demonstrates nicely how this system can be used to study gene regulation during development," says Professor Nikolaus Rajewsky, Scientific Director of MDC's Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB), who oversaw the project. "We look forward to applying this parallel genomic editing approach to more questions."

INFORMATION:

Scientific contacts

Jonathan Fröhlich

Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements Lab

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

Jonathan.fröhlich@mdc-berlin.de

Bora Uyar

Bioinformatics and Omics Data Science Platform

Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

bora.uyar@mdc-berlin.de

Professor Nikolaus Rajewsky

Head of Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements Lab

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

Nikolaus.rajewsky@mdc-berlin.de

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) was founded in Berlin in 1992. It is named for the German-American physicist Max Delbrück, who was awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. The MDC's mission is to study molecular mechanisms in order to understand the origins of disease and thus be able to diagnose, prevent and fight it better and more effectively. In these efforts the MDC cooperates with the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) as well as with national partners such as the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and numerous international research institutions. More than 1,600 staff and guests from nearly 60 countries work at the MDC, just under 1,300 of them in scientific research. The MDC is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (90 percent) and the State of Berlin (10 percent), and is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers.