(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. - Women's increased agricultural labor during harvest season, in addition to domestic house care, often comes at the cost of their health, according to new research from the Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition (TCI).

Programs aimed at improving nutritional outcomes in rural India should account for the tradeoffs that women experience when their agricultural work increases, according to the study, "Seasonal time trade-offs and nutrition outcomes for women in agriculture: Evidence from rural India," which published in the journal Food Policy on March 24.

"To earn more income during peak seasons, landless women have no choice but to spend time in agricultural work, besides engaging in domestic work," said first author Vidya Vemireddy, a TCI alumna and assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. "In contrast, women who have larger farms or higher incomes may choose to reduce the time they spend on agriculture and household activities via hired labor or labor-saving technologies."

To see how time constraints impact women's nutritional outcomes, Vemireddy and TCI director Prabhu Pingali surveyed 960 women from rural Maharashtra, India, about their time use and diets. Their work included an index of standardized local recipes to measure nutrient intake and cooking time.

Pingali is also a professor in the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, with joint appointments in the Division of Nutritional Sciences and the Department of Global Development in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Women in rural India face severe constraints on time. They spend about 32% of their time on agricultural activities such as transplanting, weeding and harvesting, while also responsible for unpaid household labor like cooking, cleaning, fetching water and caring for children, Vemireddy and Pingali say. This workload increases during peak agricultural seasons, when they must spend up to five and a half hours per day sowing and harvesting.

Men, by comparison, face fewer time constraints since they spend very little time doing housework.

During peak agricultural seasons, the increased labor leaves women with less time for other personal activities. Vemireddy and Pingali found that these time trade-offs are associated with a decrease in caloric, protein, iron and zinc intake. More specifically, each 100-rupee increase in a woman's agricultural wages per day - meaning she spent more time working on the farm - is associated with a loss of 112.3 calories, 1.5 g of protein, 0.7 mg of iron and 0.4 mg of zinc.

This decrease is likely due to the women having less time and energy to cook nutritious meals, according to Pingali. "Most of the women we surveyed cooked two meals per day," Pingali said. "When faced with a longer workday on the farm, they might have less time to cook in the morning or be too tired in the evening, choosing instead to make easier, less time-consuming, and less nutritious dishes."

These nutritional deficits are worse for landless women who work on other people's farms, grow only food crops, or grow a mix of food and cash crops. By contrast, women who own large tracts of land and specialize in cash crops like cotton see little decline in nutrition during peak seasons, possibly because they have higher incomes.

The negative relationship between women's nutrition and increased farm work has important implications for development programs and interventions that seek to use agriculture to improve nutrition outcomes, such as encouraging households to grow kitchen gardens, the researchers said.

"Agricultural policies and programs that require greater involvement of women must recognize the consequences of increased time burdens and their adverse effects on nutrition," Vemireddy said. "The programs should be designed in such a way that the benefits of women's participation in agriculture outweigh the losses, such as time for well-being enhancing activities."

Vemireddy and Pingali said labor-saving strategies and technologies can lower the burdens placed on women by agricultural and household labor.

However, they said, managing time burdens alone can only improve nutrition so much. Successfully addressing malnutrition in India will still require a reorientation of the country's food policies to make nutrient-rich foods more accessible and affordable.

INFORMATION:

PHILADELPHIA-- Humans have a uniquely high density of sweat glands embedded in their skin--10 times the density of chimpanzees and macaques. Now, researchers at Penn Medicine have discovered how this distinctive, hyper-cooling trait evolved in the human genome. In a study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, researchers showed that the higher density of sweat glands in humans is due, to a great extent, to accumulated changes in a regulatory region of DNA--called an enhancer region--that drives the expression of a sweat gland-building gene, explaining why humans are the sweatiest ...

PHOENIX, Ariz. -- April 13, 2021 -- Findings of a study by the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), an affiliate of City of Hope, suggest that increasing expression of a gene known as ABCC1 could not only reduce the deposition of a hard plaque in the brain that leads to Alzheimer's disease, but might also prevent or delay this memory-robbing disease from developing.

ABCC1, also known as MRP1, has previously been shown in laboratory models to remove a plaque-forming protein known as amyloid beta (Abeta) from specialized endothelial cells that surround and protect ...

Compared to newborns conceived traditionally, newborns conceived through in vitro fertilization (IVF) are more likely to have certain chemical modifications to their DNA, according to a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health. The changes involve DNA methylation--the binding of compounds known as methyl groups to DNA--which can alter gene activity. Only one of the modifications was seen by the time the children were 9 years old.

The study was conducted by Edwina Yeung, Ph.D., and colleagues in NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human ...

A team of UBC Okanagan researchers has determined that the type of fats a mother consumes while breastfeeding can have long-term implications on her infant's gut health.

Dr. Deanna Gibson, a biochemistry researcher, along with Dr. Sanjoy Ghosh, who studies the biochemical aspects of dietary fats, teamed up with chemistry and molecular biology researcher Dr. Wesley Zandberg. The team, who conducts research in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science, explored the role of feeding dietary fat to gestating rodents to determine the generational effects of fat exposure on their offspring.

"The goal was to investigate how maternal dietary habits can impact an offspring's gut microbial communities and their associated sugar molecule patterns ...

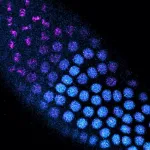

HANOVER, N.H. - April 14, 2021 - Scientists have searched for years to understand how cells measure their size. Cell size is critical. It's what regulates cell division in a growing organism. When the microscopic structures double in size, they divide. One cell turns into two. Two cells turn into four. The process repeats until an organism has enough cells. And then it stops. Or at least it is supposed to.

The complete chain of events that causes cell division to stop at the right time is what has confounded scientists. Beyond being a textbook problem, the question relates to serious medical challenges: ...

LOS ANGELES (April 13, 2021) -- The Lundquist Institute (TLI) Investigator Dong W. Chang, MD, and his colleagues' study on critically ill patients and ICU treatments was published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The study - "Evaluation of Time-Limited Trials Among Critically Ill Patients with Advanced Medical Illnesses and Reduction of Nonbeneficial ICU Treatments" - found that training physicians to communicate with family members of critically ill patients using a structured approach, which promotes shared decision-making, improved the quality of family meetings. This intervention was associated with reductions in invasive ICU treatments that prolonged suffering without benefit for patients and their families.

"Invasive ICU treatments are frequently delivered to patients ...

In April 2019, scientists released the first image of a black hole in galaxy M87 using the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). However, that remarkable achievement was just the beginning of the science story to be told.

Data from 19 observatories released today promise to give unparalleled insight into this black hole and the system it powers, and to improve tests of Einstein's General Theory of Relativity.

"We knew that the first direct image of a black hole would be groundbreaking," says Kazuhiro Hada of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, a co-author of a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters that ...

If global warming continues unchecked, summer monsoon rainfall in India will become stronger and more erratic. This is the central finding of an analysis by a team of German researchers that compared more than 30 state-of-the-art climate models from all around the world. The study predicts more extremely wet years in the future - with potentially grave consequences for more than one billion people's well-being, economy, food systems and agriculture.

"We have found robust evidence for an exponential dependence: For every degree Celsius of warming, monsoon rainfalls will likely increase by about 5%," says lead author Anja Katzenberger from the Potsdam-Institute ...

A team of scientists, led by the University of Bristol, with colleagues from Goethe University, Frankfurt, has found the first evidence for ancient honey hunting, locked inside pottery fragments from prehistoric West Africa, dating back some 3,500 years ago.

Honeybees are an iconic species, being the world's most important pollinator of food crops. Honeybee hive products, including beeswax, honey and pollen, used both for food and medicinal purposes, support livelihoods and provide sources of income for local communities across much of Africa, through both beekeeping ...

A potential treatment for dementia and epilepsy could look to reduce the amounts of a toxic gas in the brain has been revealed in a new study using rat brain cells.

The research published in Scientific Reports today [Wednesday 14 April] shows that treatments to reduce levels of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in the brain may help to ward off damage caused by the gas. By testing rat brain cells, the team of scientists from the University of Reading, University of Leeds and John Hopkins University in the USA found that H2S is involved in blocking a key brain cell gateway ...