(Press-News.org) Language is one of the most notable abilities humans have. It allows us to express complex meanings and transmit knowledge from generation to generation. An important question in human biology is how this ability ended up being developed, and researchers from the universities of Barcelona, Cologne and Tokyo have treated this issue in a recent article.

Published in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences, the article counts on the participation of the experts from the Institute of Complex Systems of the UB (UBICS) Thomas O'Rourke and Pedro Tiago Martins, led by Cedric Boeckx, ICREA research professor at the Faculty of Philology and Communication. According to the new study, the evolution of the language would be related to another notable feature of the Homo Sapiens: tolerance and human cooperation.

The study is based on evidence from diverse fields such as archaeology, evolutionary genomics, neurobiology, animal behaviour and clinical researcher on neuropsychiatric disorders. With these, it shows that the reduction of reactive aggressiveness, resulting from the evolution and process of self-domestication of our species, could have led to an increase in the complexity of speech. According to the authors, this development would be caused by the lowest impact on brain networks of stress hormones, neurotransmitters that activate in aggressive situations, and which would be crucial when learning to speak. To show this interaction, researchers analysed the genomic, neurobiological and singing-type differences between the domesticated Bengalese finch and its closest wild relative.

Looking for keys of the human language evolution in bird singing

A central aspect of the approach of the authors regarding the evolution of the language is that the aspects that make it special can be elucidated by comparing them to other animals' communication systems. "For instance, see how kids learn to talk and how birds learn to sing: unlike most animal communication systems, young birds' singing and the language of kids are only properly developed in presence of adult tutors. Without the vocal support from adults, the great range of sounds available for humans and singing birds does not develop properly", note researchers.

Moreover, although speaking and bird singing evolved independently, authors suggest both communication systems are associated with similar patterns in the brain connectivity and are negatively affected by stress: "Birds that are regularly under stress during their development sing a more stereotypical song as adults, while children with chronic stress problems are more susceptible to developing repetitive tics, including vocalizations in the case of Tourette syndrome".

In this context, Kazuo Okanoya, one of the authors of the article, has been studying the Bengalese finch (Lonchura striata domestica) for years. This domesticated singing bird sings a more varied and complex song than its wild ancestor. The study shows that the same happens with other domesticated species: the Bengalese finch has a weakened response to stress and is less aggressive than its wild relative. In fact, according to the authors, there is more and more "evidence of multiple domesticated species to have altered vocal repertoires compared to their wild counterparts".

The impact of domestication in stress and aggressiveness

For the researchers, these differences between domestic and wild animals are "the central pieces in the puzzle of the evolution of human language", since our species shares with other domestic animals particular physical changes related to their closest wild species. Modern humans have a plain face, a round skull and a reduced size of teeth compared to our extinct archaic relatives, Neanderthals. Domestic animals have comparable changes in facial and cranial bone structures, often accompanied by the development of other traits such as skin depigmentation, floppy ears and curly tails. Last, modern humans have marked reductions in the response measures to stress and reactive aggression compared to other living apes. These similarities do not stop with physical since, according to researchers, the genomes of modern humans and multiple domesticated species show changes focused on the same genes.

In particular, a disproportionate number of these genes would negatively regulate the activity of the glutamate neurotransmitter system, which drives the brain's response to stressful experiences. Authors note that "glutamate, the brain's main excitatory neurotransmitter, dopamine, in learning birdsong, aggressive behaviour, and the repetitive vocal tics of Tourette syndrome".

Alterations in stress hormone balance in the striated body

In the study, authors show how the activity of glutamate tends to promote the release of dopamine in the striated body, an evolutionary old brain structure important for learning which is based on rewards and motor activities. "In adult songbirds, the increase in dopamine release in this striatal area is correlated to the learning of a more restricted song, which replaces experimental vocalizations typical of young birds". "Regarding human beings and other mammals -authors add-, dopamine release in the dorsal striatum promotes restrictive and repetitive motor activities, such as vocalizations, while other more experimental and exploratory behaviours are supported by the dopaminergic activity of the ventral striatum". According to the study, many of the involved genes in the glutamatergic activation that changed in the recent human evolution, codify the signalling of receptors that reduce the excitation of the dorsal striatum. That is, these reduce the dopamine release in this area. Meanwhile, these receptors tend not to reduce, and even promote, the dopamine release in ventral striatal regions.

The authors say these alterations in the balance of stress hormones in the striated body were an important advance in the evolution of vocal speech in the lineage of modern humans. "These results suggest the glutamate system and its interactions with dopamine are involved in the process in which humans acquired their varied and flexible ability to speak. Therefore, the natural selection against reactive aggressiveness that took place in our species would have altered the interaction of these neurotransmitters promoting the communicative skills of our species. These findings shed light on new ways for comparative biological research on the human ability of speech" conclude researchers.

INFORMATION:

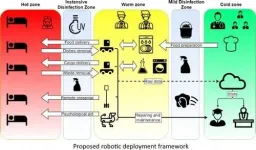

In December 2019, a new viral infection was detected in Wuhan, China. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, and on March 11, the COVID-19 pandemic. In light of the danger that the infection poses to human personnel, the idea to utilize automation in hospitals is one of the natural solutions in healthcare.

Among the paper's five co-authors, four are working in robotics and one is an expert in medicine. The paper presents a new concept of an infectious hospital that may become a worldwide standard in the future. The idea of this appeared while the authors ...

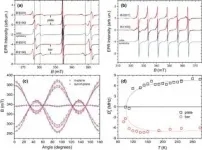

While studying strontium titanate with electron paramagnetic resonance, a team from KFU's Center for Quantum Technology has found that the shape of a specimen of strontium titanate influences its internal symmetry. The research was co-conducted by the Ioffe Institute of Physics and Technology (Russia) and the Institute of Physics of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

At room temperature, SrTiO3 is a crystal with high cubic symmetry, that is, the lattice of strontium titanate, like bricks, is composed of unit cells, each of which is a regular cube. However, the researchers showed the picture is a bit more nuanced. In ...

The research is conducted by Kazan University's Open Lab Gene and Cell Technologies (Center for Precision and Regenerative Medicine, Institute of Fundamental Medicine and Biology) and Republic Clinical Hospital of Kazan. Lead Research Associate Yana Mukhamedshina serves as project head.

Spinal cord injury mechanisms include primary and secondary injury factors. Primary injury is mechanical damage to the nervous tissue and vasculature with immediate cell death and hemorrhage. Secondary damage leads to significant destructive changes in the nervous tissue due to the development of excitotoxicity, death ...

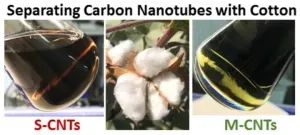

The project was kickstarted in 2017 when a delegation of YTC America (subsidiary of Yazaki Corporation) visited Kazan Federal University. During the talks, YTC suggested that KFU participate in developing effective methods of separating single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) into metallic and semiconducting specimens. This was to be done on Tuball tubes produced by OCSiAl, since they are the only ones currently available in industrial quantities.

Carbon nanotubes (CNT) is a family of 1D nanostructures with numerous verified applications, made possible due to their ...

A recent study finds that social inequality persists, regardless of educational achievement - particularly for men.

"Education is not the equalizer that many people think it is," says Anna Manzoni, author of the study and an associate professor of sociology at North Carolina State University.

The study aimed to determine the extent to which a parent's social status gives an advantage to their children. The research used the educational achievements of parents as a proxy for social status, and looked at the earnings of adult children as a proxy for professional success.

To ...

ADELPHI, Md. -- Spoken dialogue is the most natural way for people to interact with complex autonomous agents such as robots. Future Army operational environments will require technology that allows artificial intelligent agents to understand and carry out commands and interact with them as teammates.

Researchers from the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, known as DEVCOM, Army Research Laboratory and the University of Southern California's Institute for Creative Technologies, a Department of Defense-sponsored University Affiliated Research Center, created an approach to flexibly interpret and respond to Soldier intent derived from spoken dialogue with autonomous systems.

This technology is currently the primary ...

The Andes Mountains of South America are the most species-rich biodiversity hotspot for plant and vertebrate species in the world. But the forest that climbs up this mountain range provides another important service to humanity.

Andean forests are helping to protect the planet by acting as a carbon sink, absorbing carbon dioxide and keeping some of this climate-altering gas out of circulation, according to new research published in Nature Communications.

The study -- which draws upon two decades of data from 119 forest-monitoring plots in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Argentina -- was produced by an international team of scientists including researchers supported by the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University in St. Louis. The lead author was Alvaro Duque from the ...

A team of scientists from Russia studied the role of double-stranded fragments of the maturing RNA and showed that the interaction between distant parts of the RNA can regulate gene expression. The research was published in Nature Communications.

At school, we learn that DNA is double-stranded and RNA is single-stranded, but that is not entirely true. Scientists have encountered many cases of RNA forming a double-stranded (a.k.a. secondary) structure that plays an important role in the functioning of RNA molecules. These structures are involved in the regulation of gene expression, where the double-stranded regions typically carry specific functions and, if lost, may cause severe disorders. A double-stranded structure is created by sticky complementary ...

New, detailed study of the Renland Ice Cap offers the possibility of modelling other smaller ice caps and glaciers with significantly greater accuracy than hitherto. The study combined airborne radar data to determine the thickness of the ice cap with on-site measurements of the thickness of the ice cap and satellite data. Researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute - University of Copenhagen gathered the data from the ice cap in 2015, and this work has now come to fruition in the form of more exact predictions of local climate conditions.

The accuracy ...

A new study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins and the University of Pennsylvania uses computer modeling to suggest that eviction bans authorized during the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the infection rate and not only protected those who would have lost their housing but also entire communities from the spread of infections.

With widespread job loss in the U.S. during the pandemic, many state and local governments temporarily halted evictions last spring, and just as these protections were about to expire in September, the Centers for Disease Control ...