(Press-News.org) Like superheroes capable of seeing through obstacles, environmental regulators may soon wield the power of all-seeing eyes that can identify violators anywhere at any time, according to a new Stanford University-led study. The paper, published the week of April 19 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), demonstrates how artificial intelligence combined with satellite imagery can provide a low-cost, scalable method for locating and monitoring otherwise hard-to-regulate industries.

(WATCH VIDEO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LHvRgKmJOK8)

"Brick kilns have proliferated across Bangladesh to supply the growing economy with construction materials, which makes it really hard for regulators to keep up with new kilns that are constructed," said co-lead author Nina Brooks, a postdoctoral associate at the University of Minnesota's Institute for Social Research and Data Innovation who did the research while a PhD student at Stanford.

While previous research has shown the potential to use machine learning and satellite observations for environmental regulation, most studies have focused on wealthy countries with dependable data on industrial locations and activities. To explore the feasibility in developing countries, the Stanford-led research focused on Bangladesh, where government regulators struggle to locate highly pollutive informal brick kilns, let alone enforce rules.

A growing threat

Bricks are key to development across South Asia, especially in regions that lack other construction materials, and the kilns that make them employ millions of people. However, their highly inefficient coal burning presents major health and environmental risks. In Bangladesh, brick kilns are responsible for 17 percent of the country's total annual carbon dioxide emissions and - in Dhaka, the country's most populous city - up to half of the small particulate matter considered especially dangerous to human lungs. It's a significant contributor to the country's overall air pollution, which is estimated to reduce Bangladeshis' average life expectancy by almost two years.

"Air pollution kills seven million people every year," said study senior author Stephen Luby, a professor of infectious diseases at Stanford's School of Medicine. "We need to identify the sources of this pollution, and reduce these emissions."

Bangladesh government regulators are attempting to manually map and verify the locations of brick kilns across the country, but the effort is incredibly time and labor intensive. It's also highly inefficient because of the rapid proliferation of kilns. The work is also likely to suffer from inaccuracy and bias, as government data in low-income countries often does, according to the researchers.

Eye in the sky

Since 2016, Brooks, Luby and other Stanford researchers have worked in Bangladesh to pinpoint kiln locations, quantify brick kilns' adverse health effects and provide transparent public information to inform political change. They had developed an approach using infrared to pick out coal-burning kilns from remotely sensed data. While promising, the approach had serious flaws, such as the inability to distinguish between kilns and heat-trapping agricultural land.

Working with Stanford computer scientists and engineers, as well as scientists at the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), the team shifted focus to machine learning.

Building on past applications of deep-learning to environmental monitoring, and on specific efforts to use deep learning to identify brick kilns, they developed a highly accurate algorithm that not only identifies whether images contain kilns but also learns to localize kilns within the image. The method rebuilds kilns that have been fragmented across multiple images - an inherent problem with satellite imagery - and is able to identify when multiple kilns are contained within a single image. They are also able to distinguish between two kiln technologies - one of which is banned - based on shape classification.

Sobering findings

The approach revealed that more than three-fourths of kilns in Bangladesh are illegally constructed within 1 kilometer (six-tenths of a mile) of a school, and almost 10 percent are illegally close to health facilities. It also showed that the government systematically under-reports kilns with respect to regulations and - according to the shape classification findings - over-reports the percentage of kilns using a newer, cleaner technology relative to an older, banned approach. The researchers also found higher numbers of registered kilns in districts adjacent to the banned districts, suggesting kilns are formally registered in the districts where they are legal but constructed across district borders.

The researchers are working to improve the approach's limitations by developing ways to use lower resolution imagery as well as expand their work to other regions where bricks are constructed similarly. Getting it right could make a big difference. In Bangladesh alone, almost everyone lives within 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) of a brick kiln, and more than 18 million - more than twice the population of New York City - live within 1 kilometer (.6 mile), according to the researchers estimates.

"We are hopeful our general approach can enable more effective regulation and policies to achieve better health and environmental outcomes in the future," said co-lead author Jihyeon Lee, a researcher in Stanford's Sustainability and Artificial Intelligence Lab.

INFORMATION:

Luby is also a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Stanford Maternal & Child Health Research Institute. Co-authors of the study also include Fahim Tajwar, an undergraduate student in computer science; Marshall Burke, an associate professor of Earth system science in Stanford's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth), a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research; Stefano Ermon, an assistant professor of computer science in Stanford's School of Engineering and a center fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment; David Lobell, the Gloria and Richard Kushel Director of the Center on Food Security and the Environment, a professor of Earth System Science; the William Wrigley Senior Fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research; and Debashish Biswas, an assistant scientist at the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b).

The research was funded by the Stanford King Center for Global Development, the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and the National Science Foundation.

A new type of collective behaviour in ants has been revealed by an international team of scientists, headed by biologist Professor Iain Couzin, co-director of the Cluster of Excellence "Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behaviour" at the University of Konstanz and director at the co-located Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, and Matthew Lutz, a postdoctoral researcher in Couzin's lab. Their research shows how ants use self-organized architectural structures called "scaffolds" to ensure traffic flow on sloped surfaces. Scaffold formation results from individual sensing and decision-making, ...

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and collaborators at other institutions have discovered that POT1, a gene known to be associated with risk of glioma, the most common type of malignant brain tumor, mediates its effects in a sex-specific manner. Researchers found that female mice with glioma that lacked the gene survived less than males. This led them to investigate human glioma cells, where they found that low POT1 expression correlated with reduced survival in females.

Published in the journal Cancer Research, the study also shows that, compared to males', female tumors had reduced expression of immune signatures and increased expression of cell replication markers, suggesting that the immune response and tumor cell proliferation seemed to be ...

Scientists at VCU Massey Cancer Center have identified a protein that operates in tandem with a specific genetic mutation to spur lung cancer growth and could serve as a therapeutic target to treat the disease.

Mutations in the p53 gene are found in more than half of all cancers, but it remains difficult to effectively target the gene with drugs even decades after its discovery. Though previous research has shown that p53 acts as a tumor suppressor and initiates cancer cell death in its natural state, a new study led by Sumitra Deb, Ph.D., suggests that gain-of-function (GOF) mutations -- a type of mutation where the changed gene has an added function ...

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., April 19, 2021--A new machine-learning program accurately identifies COVID-19-related conspiracy theories on social media and models how they evolved over time--a tool that could someday help public health officials combat misinformation online.

"A lot of machine-learning studies related to misinformation on social media focus on identifying different kinds of conspiracy theories," said Courtney Shelley, a postdoctoral researcher in the Information Systems and Modeling Group at Los Alamos National Laboratory and co-author of the study that was published last week in the Journal of ...

PHILADELPHIA-- A retrospective study led by researchers from Penn Medicine found that with MitraClip for treatment of secondary mitral regurgitation (MR), a heart disease associated with problems in the left ventricle, there was no negative effect of having a slightly smaller mitral valve opening as long as there was good reduction of the mitral regurgitation. The study is published today in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

"This data is very reassuring for physicians who place MitraClips in patients with secondary mitral regurgitation. It demonstrates that the benefits of MR reduction in patients with heart failure were maintained even when mild-to-moderate mitral stenosis, which can be caused by a narrowing of the ...

While cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death globally, new research led by NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Moi University School of Medicine (Kenya) found that addressing and incorporating social determinants of health (such as poverty and social isolation) in the clinical management of blood pressure in Kenya can improve outcomes for patients with diabetes or hypertension.

The study -- recently published online in The Journal of the American College of Cardiology - found that after one year, patients who received a multi-component intervention that combined community microfinance groups with group medical visits (where patients with similar medical conditions met together with a clinician and community health worker) ...

A first-of-its-kind study led by The University of Texas at Austin has found that rock weathering and water storage appear to follow a similar pattern across undulating landscapes where hills rise and fall for miles.

The findings are important because they suggest that these patterns could improve predictions of wildfire and landslide risk and how droughts will affect the landscape, since weathering and water storage influence how water and nutrients flow throughout landscapes.

"There's a lot of momentum to do this work right now," said study co-author Daniella Rempe, an assistant professor at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences Department of Geological Sciences. "This kind of data, across large scales, is what is needed to inform next-generation models of land-surface processes."

The ...

The fact that the human body is made up of cells is a basic, well-understood concept. Yet amazingly, scientists are still trying to determine the various types of cells that make up our organs and contribute to our health.

A relatively recent technique called single-cell sequencing is enabling researchers to recognize and categorize cell types by characteristics such as which genes they express. But this type of research generates enormous amounts of data, with datasets of hundreds of thousands to millions of cells.

A new algorithm developed by Joshua Welch, Ph.D., of the Department of Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, Ph.D. candidate Chao Gao and their team uses online learning, greatly speeding up this process and providing a way for researchers ...

A lot about the human brain and its intricacies continue to remain a mystery. With the advancement of neurobiology, the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases (ND) has been uncovered to a certain extent along with molecular targets around which current therapies revolve. However, while the current treatments offer temporary symptomatic relief and slow down the course of the disease, they do not completely cure the condition and are often accompanied by a myriad of side effects that can impair normal daily functions of the patient.

Light stimulation has been proposed as a promising therapeutic alternative for treating various ND like ...

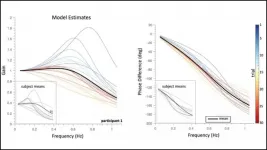

The brain's auditory system tracks the speed and location of moving sounds in the same way the visual system tracks moving objects. The study recently published in eNeuro lays the groundwork for more detailed research on how humans hear in dynamic environments.

People who use hearing aids have trouble discriminating sounds in busy environments. Understanding if and how the auditory system tracks moving sounds is vital to improving hearing aid technology. Prior research utilizing eye movements to gauge whether the brain is following the trajectory of a moving sound indicates it cannot. A new study from García-Uceda Calvo et al. instead used head movements, a more accurate measure of sound tracking.

The team analyzed head movements of hearing ...