New results about the diets of people who lived on the Great Hungarian Plain

A transdisciplinary study of the dietary evolution of the first agricultural and pastoral communities in Central Europe

2021-04-21

(Press-News.org) The lifestyle and eating habits of human groups that have lived for thousands of years can be examined by tooth. An international research group analyzed the prehistoric findings of the Neolithic Age. In addition to providing knowledge about the lifestyles of people who lived in prehistoric times, a novel study of tooth remains paved the way for other methods previously not used. This study applies the complementary approaches of stable isotope and dental microwear analyses to study the diets of past people living in today's Hungary. Their joint results were published in the scientific journal Scientific Reports.

The Great Hungarian Plain is considered one of the most interesting areas for archeology because of its central geographic position in the European continent. The area played a key role in the spread and development of farming across Europe and was the meeting point for eastern and western European cultures. As such, it was a major cultural and technological transitional region throughout prehistory. But despite being a rich archeological region, few studies have analyzed the diets of the past people living in today's Hungary. In this context, researchers from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA) and the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV) in Tarragona (Spain), have carried out interdisciplinary research contributing new data about the evolution of the diets of the first agricultural and pastoral communities in Central Europe. This investigation has just been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The study is focused on Great Hungarian Plain populations that lived from Middle Neolithic (5,500 - 5,000 BC) to Late Bronze Age (1,450 - 800 BC). Important changes in human diets occurred during this timeframe, influenced, most probably, by the socioeconomic, demographical and cultural transformations characterizing this period of some 5,000 years.

Raquel Hernando is a co-author of the paper carrying out her PhD studies with the URV and IPHES-CERCA and is beneficiary of a Marti-Franqueses Research Grant (URV2019PMF-PIPF-59). She says: "The demographic increase during the transition from Neolithic to Copper Age, produced changes in the settlement pattern and an increased focus on animal husbandry with a more reliance on cattle". And she adds "With the arrival of bronze metallurgy from the eastern steppe, significant changes occurred in the intensification of agriculture, with more hierarchical societies and fortified settlements".

All of these events took place at the same time over much of the European continent and

"...had implications on the dietary subsistence patterns of the human populations of that time" points out Beatriz Gamarra, a postdoctoral Beatriu de Pinós AGAUR Fellow and co-author of the paper in collaboration with other academics of research centres and universities from Ireland, Hungary and Portugal.

The team studied the diets of past human populations living in the Great Hungarian Plain from the Middle Neolithic and Late Bronze Age periods, demonstrating that, compared with subsequent periods, people consumed less abrasive and/or more processed foods during Middle Neolithic period. The Middle Neolithic people consumed meat and cereals (like wheat, einkorn and barley), although their diets varied between the sites. The researchers also found that, although other crops were consumed increasingly during the Middle Bronze Age (such as millet), this did not have any effects on the abrasiveness of the food and the way they processed it.

These results have been obtained from the same individuals using two approaches that were found to be complementary: stable isotope and dental microwear analyses. Each method is indicative of different dietary traits and few studies have combined both of them to infer ancestral diets. In this sense, Raquel Hernando states:

"The novelty of our study is that, thanks to the rich Hungarian archaeological human record, we have been able to employ both approaches on the same individuals, something that it has rarely been applied in previous studies, and has been developed in this exhaustive work".

Dental microwear analysis applied on molars provides information about the abrasiveness of the diets and the previous process of the foods consumed. Meanwhile, the stable isotopes study provides information about the origins of the animal proteins present in the ingested foods. Beatriz Gamarra highlights:

"We have demonstrated the complementary of these two techniques, which is not very common on this kind of research, as many of the archaeological context of the samples employed (such as collective burials) do not allow for this kind of combination on the same individuals' skeletal remains."

To carry out this research, a total of 89 individuals sampled from 17 archaeological sites dating to different periods and situated in the north-eastern part of the Great Hungarian Plain were employed. The material is stored in the Herman Ottó Museum in Miskolc, Hungary. Raquel Hernando specifies:

"From each individual, we have employed their teeth (first and second molars) for the microwear study, postcranial remains for the stable isotope analysis, and the petrous bone (inner ear) to perform ancient DNA analyses in order to biologically sex them ", specifies Raquel Hernando.

Dental microwear consists of quantifying a series of marks, such as striations and pits, formed on tooth enamel surfaces during the chewing process due to the presence in the foods of particles harder than tooth enamel. Using information from the microwear patterns, the abrasiveness of the food ingested and/or the previous process the foods might suffered before its consumption, can be inferred. To avoid damaging the original remains, molds of the teeth were made during the research stay of Raquel Hernando at the University College Dublin (UCD, Ireland). These molds were later analysed at the Servei de Recursos Cienífics I Tècnics facilities of the URV (at Seslades Campus, Tarragona).

The stable isotope analyses are based on the principle that the biochemical composition of the food consumed by animals is preserved in their body tissues. The carbon and nitrogen isotopic fractions were calculated from bone collagen and are indicative of the origin of the proteins consumed by the individuals a few years prior to their death. This research was carried out by Beatriz Gamarra at the School of Archaeology of University College Dublin (Ireland) thanks to funding from her previous MSCA (Marie Sk?odowska-Curie Actions) project.

INFORMATION:

The bone samples and teeth have been analyzed in Dublin (University College Dublin), Tarragona (Seslades Campus), the University of Vienna and Harvard. While the anthropological background of the findings was provided by researchers from the Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Sciences at Eötvös Loránd University, the Hungarian Natural History Museum, and the Institute of Archaeology, ELKH-BTK. The anthropological background of the findings was provided by researchers from the Department of Anthropology and the Department of Anthropology of the Hungarian Natural History Museum (Tamás Hajdu, Tamás Szeniczey and Krisztián Kiss) and Kitti Köhler (Institute of Archaeology, ELKH BTK). The scientific work for the project in Hungary was coordinated by Tamás Hajdu, within the framework of an FK-NKFI project at the Department of Anthropology.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-21

Coronavirus researchers led by Professor Rolf Hilgenfeld of the University of Luebeck and PD Dr. Albrecht von Brunn of the Ludwig-Maximilian Universitaet (LMU) in Munich have discovered how SARS viruses enhance the production of viral proteins in infected cells, so that many new copies of the virus can be generated. Notably, coronaviruses other than SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 do not use this mechanism, which may therefore provide a possible explanation for the much higher pathogenicity of the SARS viruses. The findings appear in the EMBO Journal.

Coronaviruses that cause harmless colds in humans were discovered more than 50 years ago. When it emerged in 2002/2003, the SARS coronavirus was the first coronavirus found to cause severe pneumonia ...

2021-04-21

For more sustainability on a global level, EU legislation should be changed to allow the use of gene editing in organic farming. This is what an international research team involving the Universities of Bayreuth and Göttingen demands in a paper published in the journal "Trends in Plant Science".

In May 2020, the EU Commission presented its "Farm-to-Fork" strategy, which is part of the "European Green Deal". The aim is to make European agriculture and its food system more sustainable. In particular, the proportion of organic farming in the EU's total agricultural land is to be increased to 25 percent by 2030. However, if current EU legislation remains in place, this increase will by no means guarantee more sustainability, as the current study by scientists from Bayreuth, Göttingen, ...

2021-04-21

Meaningful legislation addressing health care inequities in the U.S. will require studies examining potential health disparities due to geographic location or economic status.

An interdisciplinary team at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) and the University of South Carolina (UofSC) report in the Journal of Public Health Dentistry that rural children are less likely to receive preventive dental care than urban children. Using samples from 20,842 respondents from a 2017 National Survey of Children's Health, the team determined the existence of an urban-rural disparity in U.S. children's oral health. ...

2021-04-21

After pouring beer into a glass, streams of little bubbles appear and start to rise, forming a foamy head. As the bubbles burst, the released carbon dioxide gas imparts the beverage's desirable tang. But just how many bubbles are in that drink? By examining various factors, researchers reporting in ACS Omega estimate between 200,000 and nearly 2 million of these tiny spheres can form in a gently poured lager.

Worldwide, beer is one of the most popular alcoholic beverages. Lightly flavored lagers, which are especially well-liked, are produced through a cool fermentation process, converting the sugars in malted grains to alcohol and carbon dioxide. During commercial packaging, more carbonation can be added to get a desired level of fizziness. That's ...

2021-04-21

(Boston)--A major obstacle in understanding and treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is its clinical and neurobiological heterogeneity. In order to better treat the condition and address this barrier, the field has become increasingly interested in identifying subtypes of PTSD based on dysfunction in neural networks alongside cognitive impairments that may underlie the development and maintenance of symptoms.

VA and BU researchers have now found a marker of PTSD in brain regions associated with emotional regulation. "This marker was strongest in those with clinically impaired executive function or the ability to engage in complex ...

2021-04-21

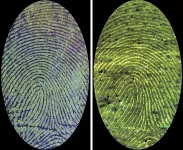

Careful criminals usually clean a scene, wiping away visible blood and fingerprints. However, prints made with trace amounts of blood, invisible to the naked eye, could remain. Dyes can detect these hidden prints, but the dyes don't work well on certain surfaces. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces have developed a fluorescent polymer that binds to blood in a fingerprint -- without damaging any DNA also on the surface -- to create high-contrast images.

Fingerprints are critical pieces of forensic evidence because their whorls, loops and arches are unique to each person, and these patterns don't change as people age. When violent crimes are committed, a culprit's fingerprints inked in ...

2021-04-21

Water touches virtually every aspect of human society, and all life on earth requires it. Yet, fresh, clean water is becoming increasingly scarce -- one in eight people on the planet lack access to clean water. Drivers of freshwater salt pollution such as de-icers on roads and parking lots, water softeners, and wastewater and industrial discharges further threaten freshwater ecosystem health and human water security.

"Inland freshwater salt pollution is rising nationwide and worldwide, and we investigated the potential conflict between managing freshwater salt ...

2021-04-21

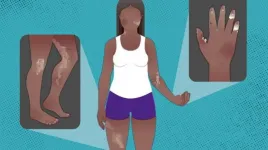

Screening for a sometimes fatal condition among patients with a rare autoimmune disease could soon - thanks to a computer algorithm - become even more accurate.

Researchers at Michigan Medicine found that an internet application improved their ability to spot pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma. The unpredictable condition is marked by tightening of the skin that can damage internal organs.

The algorithm, aptly named DETECT, outperformed standard methods used to identify the form of high blood pressure in the lungs that causes the heart to weaken and fail.

"We've been advocating for a long time that every scleroderma patient should be screened on an annual basis using DETECT, and ...

2021-04-21

BETHESDA, Md. -- The COVID-19 pandemic heavily influenced spending on prescription drugs in the U.S. in 2020, according to the ASHP's (American Society of Health-System Pharmacists) National Trends in Prescription Drug Expenditures and Projections for 2021. Shifts in care related to the pandemic will continue to be a significant driver of drug expenditures in 2021, along with uptake in the use of biosimilars, a large pipeline of new cancer drugs, and increased approvals of specialty medications.

Prescription drug spending in 2020 grew at a moderate rate of 4.9% to $535.3 billion. Increased utilization drove the ...

2021-04-21

Published in the Advanced Functional Materials, University of Minnesota researcher Hongbo Pang led a cross-institutional study on improving the efficacy of nucleotide-based drugs against prostate cancer and bone metastasis.

In this study, Pang and his research team looked at whether liposomes, when integrated with the iRGD peptide, will help concentrate antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) into primary prostate tumors and its bone metastases. Liposomes are used as a drug carrier system, and ASOs are a type of nucleotide drug.

More importantly, they investigated whether this system ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New results about the diets of people who lived on the Great Hungarian Plain

A transdisciplinary study of the dietary evolution of the first agricultural and pastoral communities in Central Europe