(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- A new approach to gene editing using the CRISPR/Cas9 system bypasses disease-causing mutations in a gene, enabling treatment of genetic diseases linked to a single gene, such as cystic fibrosis, certain types of sickle cell anemia, and other rare diseases. The method, developed and tested in mice and human tissue cultures by researchers at Penn State, involves inserting a new, fully functional copy of the gene that displaces the mutated gene.

A proof-of-concept for the approach is described in a paper appearing online April 20 in the journal Molecular Therapy.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has allowed promising new gene therapies that can target and correct disease-causing mutations in a gene. In this process, Cas9--a bacterial protein--cuts DNA at a specific location, where the genetic sequence can then be edited, trimmed, or a new sequence inserted before the DNA is repaired. However, there are two main limitations to current repair strategies. First, the common repair strategy, called "homology-directed repair," requires using specific proteins within the cell that are only present during cell division, which means the gene repair process cannot be used in most adult tissues where cell division occurs rarely.

"The second challenge stems from the fact that even when a disease is caused by a single gene, it can result from a variety of different mutations within that gene," said Douglas Cavener, professor of biology at Penn State and senior author of the paper. "With homology-directed repair, we'd need to design and test the strategy for each and every one of those mutations, which can be expensive and time-intensive. In this study, we designed an approach called Co-opting Regulation Bypass Repair (CRBR), which can be used in both dividing and non-dividing cells and tissues and for a spectrum of mutations within a gene. This approach is especially promising for rare genetic diseases caused by a single gene, where limited time and resources typically preclude design and testing for the many possible disease-causing mutations."

CRBR takes advantage of the CRISPR/Cas9 system and a cellular repair pathway called "non-homologous end joining" to insert a genetic sequence between a mutated gene's promoter region--the genetic sequence that controls when and where the gene is functional--and the mutated portion of the gene. The newly inserted sequence contains a condensed version of the normal gene that is used in place of the mutated version. A terminator sequence at the end of the inserted sequence prevents the remaining downstream mutated gene from being used. Because CRBR does not rely on the proteins required by homology-directed repair, it can be used in all types of adult tissues.

"Our approach co-opts the native promoter for a gene," said Jingjie Hu, a graduate student at Penn State and first author of the paper. "This means that the newly inserted gene will be expressed at the same times and at appropriate levels within the cell as the gene it is replacing. This is an advantage to other types of gene therapies, which rely on an external promoter to drive high levels of expression of the gene that could lead to negative effects if too much is produced or if essential regulation response is missing under certain physiological conditions."

The research team conducted a series of proof-of-concept experiments to demonstrate the utility of this method. They first focused on the PERK gene, mutations in which can lead to a rare disease called Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. The syndrome results when copies of the gene inherited from both parents have mutations--it is a "recessive" disease--and can cause neonatal diabetes, skeletal problems, growth delay, and other symptoms.

The researchers inserted the PERK gene in healthy mice using CRBR and bred them with mice that had a mutation in the gene. The resulting mice, which contained one CRBR-edited PERK gene and one mutated PERK gene, did not have the typical abnormalities associated with the syndrome, indicating that the CRBR-edited gene can rescue PERK gene function in a mouse model of the Wolcott-Rallison syndrome.

Next, the researchers tested the CRBR method in human tissues in the laboratory, in this case focusing on the insulin gene. They inserted a green fluorescent protein marker gene sequence between the insulin gene promoter and the insulin coding sequence in human cadaver cells. This experiment resulted in the expression of the fluorescent protein in insulin secreting cells, but not other cell types, which suggests the new sequence was strictly regulated under the control of insulin promoter.

"Our results demonstrated that CRBR gene repair can restore PERK gene function in mice and revealed the potential utility of CRBR for gene repair in human tissue," said Hu.

The researchers note that gene editing with CRISPR/Cas9 can be error prone. For example, homology-directed repair-based strategies could potentially produce damaging mutations in the coding sequence if repair does not happen properly. With CRBR, the researchers target the insertion within a region of the gene that does not code for protein, which should be more tolerant of these errors.

"Gene therapies such as CRBR that utilize CRISPR/Cas9 continue to face the challenge of delivery repair machinery into the cells of interest," said Cavener. "One promising development is to isolate cells or tissues from the afflicted patient, repair a mutant gene in the laboratory, and then transplant the repaired cells or tissues back into the patient. We hope that, as researchers continue to improve delivery methods, CRBR can be utilized to treat Wolcott-Rallison syndrome as well other human genetic diseases."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Cavener and Hu, the research team at Penn State includes research assistant Rebecca Bourne; Associate Research Professor of Biology Barbara McGrath; undergraduate student Alice Lin; and Assistant Research Professor of Biology Zifei Pei.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of health and the Penn State Eberly College of Science Verne M. Willaman Dean's chair.

The number of solar panels within shortest distance from a house is the most important factor in determining the likelihood of that house having a solar panel, when compared with a host of socio-economic and demographic variables. This is shown in a new study by scientists using satellite and census data of the city of Fresno in the US, and employing machine learning. Although it is known that peer effects are relevant for sustainable energy choices, very high-resolution data combined with artificial intelligence techniques were necessary to single out the paramount importance of proximity. The finding is relevant for policies that aim at a broad deployment of solar panels in order to replace unsustainable ...

The lifestyle and eating habits of human groups that have lived for thousands of years can be examined by tooth. An international research group analyzed the prehistoric findings of the Neolithic Age. In addition to providing knowledge about the lifestyles of people who lived in prehistoric times, a novel study of tooth remains paved the way for other methods previously not used. This study applies the complementary approaches of stable isotope and dental microwear analyses to study the diets of past people living in today's Hungary. Their joint results were published in the scientific journal Scientific Reports.

The Great Hungarian Plain is considered one of the most interesting areas for archeology because ...

Coronavirus researchers led by Professor Rolf Hilgenfeld of the University of Luebeck and PD Dr. Albrecht von Brunn of the Ludwig-Maximilian Universitaet (LMU) in Munich have discovered how SARS viruses enhance the production of viral proteins in infected cells, so that many new copies of the virus can be generated. Notably, coronaviruses other than SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 do not use this mechanism, which may therefore provide a possible explanation for the much higher pathogenicity of the SARS viruses. The findings appear in the EMBO Journal.

Coronaviruses that cause harmless colds in humans were discovered more than 50 years ago. When it emerged in 2002/2003, the SARS coronavirus was the first coronavirus found to cause severe pneumonia ...

For more sustainability on a global level, EU legislation should be changed to allow the use of gene editing in organic farming. This is what an international research team involving the Universities of Bayreuth and Göttingen demands in a paper published in the journal "Trends in Plant Science".

In May 2020, the EU Commission presented its "Farm-to-Fork" strategy, which is part of the "European Green Deal". The aim is to make European agriculture and its food system more sustainable. In particular, the proportion of organic farming in the EU's total agricultural land is to be increased to 25 percent by 2030. However, if current EU legislation remains in place, this increase will by no means guarantee more sustainability, as the current study by scientists from Bayreuth, Göttingen, ...

Meaningful legislation addressing health care inequities in the U.S. will require studies examining potential health disparities due to geographic location or economic status.

An interdisciplinary team at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) and the University of South Carolina (UofSC) report in the Journal of Public Health Dentistry that rural children are less likely to receive preventive dental care than urban children. Using samples from 20,842 respondents from a 2017 National Survey of Children's Health, the team determined the existence of an urban-rural disparity in U.S. children's oral health. ...

After pouring beer into a glass, streams of little bubbles appear and start to rise, forming a foamy head. As the bubbles burst, the released carbon dioxide gas imparts the beverage's desirable tang. But just how many bubbles are in that drink? By examining various factors, researchers reporting in ACS Omega estimate between 200,000 and nearly 2 million of these tiny spheres can form in a gently poured lager.

Worldwide, beer is one of the most popular alcoholic beverages. Lightly flavored lagers, which are especially well-liked, are produced through a cool fermentation process, converting the sugars in malted grains to alcohol and carbon dioxide. During commercial packaging, more carbonation can be added to get a desired level of fizziness. That's ...

(Boston)--A major obstacle in understanding and treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is its clinical and neurobiological heterogeneity. In order to better treat the condition and address this barrier, the field has become increasingly interested in identifying subtypes of PTSD based on dysfunction in neural networks alongside cognitive impairments that may underlie the development and maintenance of symptoms.

VA and BU researchers have now found a marker of PTSD in brain regions associated with emotional regulation. "This marker was strongest in those with clinically impaired executive function or the ability to engage in complex ...

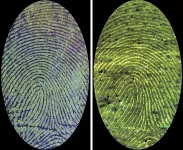

Careful criminals usually clean a scene, wiping away visible blood and fingerprints. However, prints made with trace amounts of blood, invisible to the naked eye, could remain. Dyes can detect these hidden prints, but the dyes don't work well on certain surfaces. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces have developed a fluorescent polymer that binds to blood in a fingerprint -- without damaging any DNA also on the surface -- to create high-contrast images.

Fingerprints are critical pieces of forensic evidence because their whorls, loops and arches are unique to each person, and these patterns don't change as people age. When violent crimes are committed, a culprit's fingerprints inked in ...

Water touches virtually every aspect of human society, and all life on earth requires it. Yet, fresh, clean water is becoming increasingly scarce -- one in eight people on the planet lack access to clean water. Drivers of freshwater salt pollution such as de-icers on roads and parking lots, water softeners, and wastewater and industrial discharges further threaten freshwater ecosystem health and human water security.

"Inland freshwater salt pollution is rising nationwide and worldwide, and we investigated the potential conflict between managing freshwater salt ...

Screening for a sometimes fatal condition among patients with a rare autoimmune disease could soon - thanks to a computer algorithm - become even more accurate.

Researchers at Michigan Medicine found that an internet application improved their ability to spot pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma. The unpredictable condition is marked by tightening of the skin that can damage internal organs.

The algorithm, aptly named DETECT, outperformed standard methods used to identify the form of high blood pressure in the lungs that causes the heart to weaken and fail.

"We've been advocating for a long time that every scleroderma patient should be screened on an annual basis using DETECT, and ...