(Press-News.org) RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. -- With Army funding, scientists invented a way to make compostable plastics break down within a few weeks with just heat and water. This advance will potentially solve waste management challenges at forward operating bases and offer additional technological advances for American Soldiers.

The new process, developed by researchers at University of California, Berkeley and the University of Massachusetts Amherst, involves embedding polyester-eating enzymes in the plastic as it's made.

When exposed to heat and water, an enzyme shrugs off its polymer shroud and starts chomping the plastic polymer into its building blocks -- in the case of biodegradable plastics, which are made primarily of the polyester known as polylactic acid, or PLA, it reduces it to lactic acid that can feed the soil microbes in compost. The polymer wrapping also degrades.

The process, published in Nature, eliminates microplastics, a byproduct of many chemical degradation processes and a pollutant in its own right. Up to 98% of the plastic made using this technique degrades into small molecules.

"These results provide a foundation for the rational design of polymeric materials that could degrade over relatively short timescales, which could provide significant advantages for Army logistics related to waste management," said Dr. Stephanie McElhinny, program manager, Army Research Office, an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, known as DEVCOM, Army Research Laboratory. "More broadly, these results provide insight into strategies for the incorporation of active biomolecules into solid-state materials, which could have implications for a variety of future Army capabilities including sensing, decontamination, and self-healing materials."

The new process to break down compostable plastics involves embedding polyester-eating enzymes in the plastic as it's made. When exposed to heat and water, the enzyme shrugs off its polymer shroud and starts chomping the plastic polymer into its building blocks -- in the case of PLA, reducing it to lactic acid, which can feed the soil microbes in compost.

Plastics are designed not to break down during normal use, but that also means they don't break down after they're discarded. Compostable plastics can take years to break down, often lasting as long as traditional plastics.

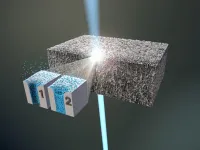

The research teams embedded nanoscale polymer-eating enzymes directly in a plastic or other material in a way that sequesters and protected them until the right conditions to unleash them. In 2018, they showed how this works in practice. The team embedded in a fiber mat an enzyme that degrades toxic organophosphate chemicals, like those in insecticides and chemical warfare agents. When the mat was immersed in the chemical, the embedded enzyme broke down the organophosphate.

The researchers said protecting the enzyme from falling apart, which proteins typically do outside of their normal environment, such as a living cell, resulted in the key innovation.

For the Nature paper, the researchers showcased a similar technique by enshrouding the enzyme in molecules they designed called random heteropolymers or RHPs, and embedding billions of these nanoparticles throughout plastic resin beads that are the starting point for all plastic manufacturing. The process is similar to embedding pigments in plastic to color them.

"This work, combined with the 2018 discovery, reveals these RHPs as highly effective enzyme stabilizers, enabling the retention of enzyme structure and activity in non-biological environments," said Dr. Dawanne Poree, program manager, ARO. "This research really opens the door to a new class of biotic-abiotic hybrid materials with functions only currently found in living systems."

Much of the planet is swimming in discarded plastic, which is harming animal and possibly human health. Can it be cleaned up?

The results showed that the RHP-shrouded enzymes did not change the character of the plastic, which could be melted and extruded into fibers like normal polyester plastic at temperatures around 170 degrees Celsius (338 degrees Fahrenheit).

To trigger degradation, it was necessary only to add water and a little heat. At room temperature, 80% of the modified PLA fibers degraded entirely within about one week. Degradation was faster at higher temperatures. Under industrial composting conditions, the modified PLA degraded within six days at 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit).

Another polyester plastic, PCL (polycaprolactone), degraded in two days under industrial composting conditions at 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit). For PLA, the team embedded an enzyme called proteinase K that chews PLA up into molecules of lactic acid; for PCL, they used lipase. Both are inexpensive and readily available enzymes.

"If you have the enzyme only on the surface of the plastic, it would just etch down very slowly," said Ting Xu, UC Berkeley professor of materials science and engineering and of chemistry. "You want it distributed nanoscopically everywhere so that, essentially, each of them just needs to eat away their polymer neighbors, and then the whole material disintegrates."

Xu suspects that higher temperatures make the enshrouded enzyme move around more, allowing it to more quickly find the end of a polymer chain and chew it up and then move on to the next chain. The RHP-wrapped enzymes also tend to bind near the ends of polymer chains, keeping the enzymes near their targets.

The modified polyesters do not degrade at lower temperatures or during brief periods of dampness. For instance, a polyester shirt made with this process would withstand sweat and washing at moderate temperatures.

Soaking the biodegradable plastic in water for three months at room temperature did not cause it to degrade, but soaking for that time period in lukewarm water did.

Xu is developing RHP-wrapped enzymes that can degrade other types of polyester plastic, but she also is modifying the RHPs so that the degradation can be programmed to stop at a specified point and not completely destroy the material. This might be useful if the plastic were to be re-melted and turned into new plastic.

"Imagine, using biodegradable glue to assemble computer circuits or even entire phones or electronics, then, when you're done with them, dissolving the glue so that the devices fall apart and all the pieces can be reused," Xu said.

This technology could be very useful for generating new materials in forward operating environments, Poree said.

"Think of having a damaged equipment or vehicle parts that can be degraded and then re-made in the field, or even repurposed for a totally different use," Poree said. "It also has potential impacts for expeditionary manufacturing."

INFORMATION:

In addition to the Army, the U.S. Department of Energy with assistance from the UC Berkeley's Bakar Fellowship program also funded the research.

Visit the laboratory's Media Center to discover more Army science and technology stories

DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory is an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command. As the Army's corporate research laboratory, ARL is operationalizing science to achieve transformational overmatch. Through collaboration across the command's core technical competencies, DEVCOM leads in the discovery, development and delivery of the technology-based capabilities required to make Soldiers more successful at winning the nation's wars and come home safely. DEVCOM is a major subordinate command of the Army Futures Command.

Women at high risk of breast cancer face cost-associated barriers to care even when they have health insurance, a new study has found.

The findings suggest the need for more transparency in pricing of health care and policies to eliminate financial obstacles to catching cancer early.

The study led by researchers at The Ohio State University included in-depth interviews with 50 women - 30 white, 20 Black - deemed at high risk of breast cancer based on family history and other factors. It appears in the Journal of Genetic Counseling.

The researchers considered it a given that women without any insurance would face serious barriers to preventive care including genetic counseling and testing, prophylactic mastectomy and ...

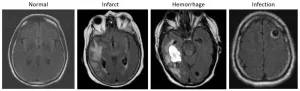

OAK BROOK, Ill. - An artificial intelligence-driven system that automatically combs through brain MRIs for abnormalities could speed care to those who need it most, according to a study published in Radiology: Artificial Intelligence.

MRI produces detailed images of the brain that help radiologists diagnose various diseases and damage from events like a stroke or head injury. Its increasing use has led to an image overload that presents an urgent need for improved radiologic workflow. Automatic identification of abnormal findings in medical images offers a potential solution, enabling improved patient care and accelerated patient discharge.

"There are an increasing number of MRIs that are performed, ...

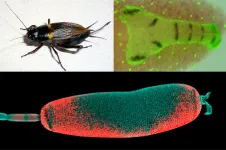

Certain signalling proteins, which are responsible for the development of innate immune function in almost all animals are also required for the formation of the dorsal-ventral (back-belly) axis in insect embryos. A new study by researchers from the University of Cologne's Institute of Zoology suggests that the relevance of these signalling proteins for insect axis formation has increased independently several times during evolution. For example, the research team found similar evolutionary patterns in the Mediterranean field cricket as in the fruit fly Drosophila, although the two insects are only very distantly related and previous observations suggested different evolutionary ...

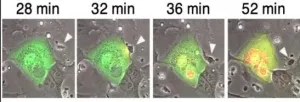

Metaplasia is defined as the replacement of a fully differentiated cell type by another. There are several classical examples of metaplasia, one of the most frequent is called Barrett's oesophagus. Barrett's oesophagus is characterized by the replacement of the keratinocytes by columnar cells in the lower oesophagus upon chronic acid reflux. This metaplasia is considered a precancerous lesion that increases by around 50 times the risk of this oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Nonetheless, the mechanisms involved in the development of metaplasia in the oesophagus are still partially unknown.

In a new study published in Cell Stem Cell, researchers led by Mr. Benjamin Beck, ...

Drawing on epidemiological field studies and the FrenchCOVID hospital cohort coordinated by Inserm, teams from the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS and the Vaccine Research Institute (VRI, Inserm/University Paris-Est Créteil) studied the antibodies induced in individuals with asymptomatic or symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. The scientists demonstrated that infection induces polyfunctional antibodies. Beyond neutralization, these antibodies can activate NK (natural killer) cells or the complement system, leading to the destruction of infected cells. Antibody levels are slightly lower in asymptomatic ...

Creativity--the "secret weapon" of Homo sapiens--constituted a major advantage over Neanderthals and played an important role in the survival of the human species. This is the finding of an international team of scientists, led by the University of Granada (UGR), which has identified for the first time a series of 267 genes linked to creativity that differentiate Homo sapiens from Neanderthals.

This important scientific finding, published today in the prestigious journal Molecular Psychiatry (Nature), suggests that it was these genetic differences linked to creativity that enabled Homo sapiens to eventually replace Neanderthals. It was creativity that gave Homo sapiens the ...

Children with weakened immune systems have not shown a higher risk of developing severe COVID-19 infection despite commonly displaying symptoms, a new study suggests.

During a 16-week period which covered the first wave of the pandemic, researchers from Southampton carried out an observational study of nearly 1500 immunocompromised children - defined as requiring annual influenza vaccinations due to underlying conditions or medication. The children, their parents or guardians completed weekly questionnaires to provide information about any symptoms they had experienced, COVID-19 test results and the impact of the pandemic on their daily life.

The results, published in BMJ Open, showed that symptoms of COVID-19 infection were common in many of the children - with ...

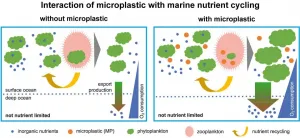

The effects of the steadily increasing amount of plastic in the ocean are complex and not yet fully understood. Scientists at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel have now shown for the first time that the uptake of microplastics by zooplankton can have significant effects on the marine ecosystem even at low concentrations. The study, published in the international journal Nature Communications, further indicates that the resulting changes may be responsible for a loss of oxygen in the ocean beyond that caused by global warming.

Plastic debris in the ocean is a widely known problem for large marine mammals, fish and seabirds. These ...

The results, exceptional first time evidence of how early flocks of domesticated sheep fed and reproduced within the Iberian Peninsula, are currently the first example of the modification of sheep's seasonal reproductive rhythms with the aim of adapting them to human needs.

The project includes technical approaches based on stable isotope analysis and dental microwear of animal remains from more than 7,500 years ago found in the Neolithic Chaves cave site in Huesca, in the central Pyrennean region of Spain. The research was coordinated from the Arqueozoology Laboratory of the UAB Department of Antiquity, with the participation of researchers from the University of Zaragoza, the Museum of Natural History of Paris, and the Catalan Institute of Human Palaeocology and Social Evolution (IPHES) ...

Most battery materials, novel catalysts, and storage materials for hydrogen have one thing in common: they have a structure comprised of tiny pores in the nanometer range. These pores provide space which can be occupied by guest atoms, ions, and molecules. As a consequence, the properties of the guest and the host can change dramatically. Understanding the processes inside the pores is crucial to develop innovative energy technologies.

Observing the filling process

So far, it has only been possible to characterise the pore structure of the substrate materials precisely. The exact structure of the adsorbate inside the pores has remained hidden. To probe this, a team from the HZB together with colleagues ...