The COVID-19 epidemic reached the United States in early 2020, rapidly spreading across several states by March. To mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, states issued stay-at-home orders, closed schools and businesses, and put in place mask mandates. In major cities like New York City and Chicago, the first wave ended in June. In the winter, a second wave broke out in both cities; indeed subsequent waves of COVID-19 have emerged throughout the world. Epidemics frequently show this common pattern of an initial wave that ends, only to be followed unexpectedly by subsequent waves, but it has been challenging to develop a detailed and quantitative understanding of this generic phenomenon.

Mathematical models of epidemics were first developed almost 100 years ago, but necessarily cannot perfectly capture reality. One of their flaws is failing to account for the structure of person-to-person contact networks, which serve as channels for the spread of infectious diseases.

"Classical epidemiological models tend to ignore the fact that a population is heterogenous, or different, on multiple levels, including physiologically and socially," said lead author Alexei Tkachenko, a physicist in the Theory and Computation Group at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN), a DOE Office of Science User Facility at Brookhaven Lab. "We don't all have the same susceptibility to infection because of factors such as age, preexisting health conditions, and genetics. Similarly, we don't have the same level of activity in our social lives. We differ in the number of close contacts we have and in how often we interact with them throughout different seasons. Population heterogeneity--these individual differences in biological and social susceptibility--is particularly important because it lowers the herd immunity threshold."

Herd immunity is the percentage of the population who must achieve immunity in order for an epidemic to end. "Herd immunity is a controversial topic," said Sergei Maslov, a CFN user and professor and Bliss Faculty Scholar at UIUC, with faculty appointments in the Departments of Physics, Bioengineering, and at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology. "Since early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been suggestions of reaching herd immunity quickly, thereby ending local transmission of the virus. However, our study shows that apparent collective immunity reached in this way will not last."

According to Nigel Goldenfeld, Swanlund Professor of Physics at UIUC, and leader of the Biocomplexity Group at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, the concept of herd immunity doesn't apply in practice to COVID-19."People's social activity waxes and wanes, especially due to lockdowns or other mitigations. So, a wave of the epidemic can seem to die away due to mitigation measures when the susceptible or more social groups collectively have been infected--something we termed transient collective immunity. But once these measures are relaxed and people's social networks are renewed, another wave can start, as we've seen with states and countries opening up too soon, thinking the worst was behind them."

Ahmed Elbanna, a Donald Biggar Willett Faculty Fellow and professor of civil and environmental engineering at UIUC, noted, transient collective immunity has profound implications for public policy. "Mitigation measures, such as mask wearing and avoiding large gatherings, should continue until the true herd immunity threshold is achieved through vaccination," said Elbanna. "We can't outsmart this virus by forcing our way to herd immunity through widespread infection because the number of infected people and number hospitalized who may die would be too high."

The nuts and bolts of predictive modelling

Over the past year, the Brookhaven-UIUC team has been carrying out various projects related to a broader COVID-19 modeling effort. Previously, they modeled how the epidemic would spread through Illinois and the UIUC campus, and how mitigation efforts would impact that spread. However, they were dissatisfied with the existing mathematical frameworks that assumed heterogeneity remains constant over time. For example, if someone is not socially active today, it would be assumed that they won't be socially active tomorrow or in the weeks and months ahead. This assumption seemed unrealistic, and their work represents a first attempt to remedy this deficiency.

"Basic epidemiological models only have one characteristic time, called the generation interval or incubation period," said Tkachenko. "It refers to the time when you can infect another person after becoming infected yourself. For COVID-19, it's roughly five days. But that's only one timescale. There are other timescales over which people change their social behavior."

In this work, the team incorporated time variations in individual social activity into existing epidemiological models. Such models work by assigning each person a probability of how likely they are to become infected if exposed to the same environment (biological susceptibility) and how likely they are to infect others (social activity). A complicated multidimensional model is needed to describe each group of people with different susceptibilities to disease. They compressed this model into only three equations, developing a single parameter to capture biological and social sources of heterogeneity.

"We call this parameter the immunity factor, which tells you how much the reproduction number drops as susceptible individuals are removed from the population," explained Maslov.

The reproduction number indicates how transmissible an infectious disease is. Specifically, the quantity refers to how many people one infected person will in turn infect. In classical epidemiology, the reproduction number is proportionate to the fraction of susceptible individuals; if the pool of susceptible individuals drops by 10 percent, so will the reproduction number. The immunity factor describes a stronger reduction in the reproduction number as the pool of susceptible individuals is depleted.

To estimate the social contribution to the immunity factor, the team leveraged previous studies in which scientists actively monitored people's social behavior. They also looked at actual epidemic dynamics, determining the immunity factor most consistent with data on COVID-19-related hospitalizations, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, and daily deaths in NYC and Chicago. The team were also able to extend their calculations to all 50 U.S. states, using earlier analyses generated by scientists at Imperial College, London.

At the city and state level, the reproduction number was reduced to a larger extent in locations severely impacted by COVID-19. For example, when the susceptible number dropped by 10 percent during the early, fast-paced epidemic in NYC and Chicago, the reproduction number fell by 40 to 50 percent--corresponding to an estimated immunity factor of four to five.

"That's a fairly large immunity factor, but it's not representative of lasting herd immunity," said Tkachenko. "On a longer timescale, we estimate a much lower immunity factor of about two. The fact that a single wave stops doesn't mean you're safe. It can come back."

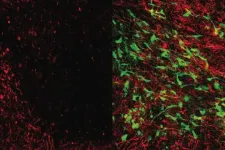

This temporary state of immunity arises because population heterogeneity is not permanent. In other words, people change their social behavior over time. For instance, individuals who self-isolated during the first wave--staying home, not having visitors over, ordering groceries online--subsequently start relaxing their behaviors. Any increase in social activity means additional exposure risk. As shown in the figure, the outcome can be that there is a false impression that the epidemic is over, although there are more waves to come.

After calibrating the model using COVID-19 data from NYC and Chicago, the team forecast future spread in both cities based on the heterogeneity assumptions they had developed, focusing on social contributions.

"Generally, social contributions to heterogeneity have a stronger effect than biological contributions, which depend on the specific biological details of the disease and thus aren't as universal or robust," explained Tkachenko.

In follow-on work, the scientists are studying epidemic dynamics in more detail. For example, they are feeding statistics from "superspreader" events--gatherings where a single infected person causes a large outbreak among attendees--into the model. They are also applying their model to different regions across the country to explain overall epidemic dynamics from the end of lockdown to early March 2021.

"Our model can be seen as a universal patch that can be applied to conventional epidemiological models to easily account for heterogeneity," said Tkachenko. "Predicting future waves will require additional considerations, such as geographic variabilities, seasonal effects, the emergence of new strains, and vaccination levels."

INFORMATION: