(Press-News.org) Much of common pharmaceutical development today is the product of laborious cycles of tweaking and optimization. In each drug, a carefully concocted formula of natural and synthetic enzymes and ingredients works together to catalyze a desired reaction. But in early development, much of the process is spent determining what quantities of each enzyme to use to ensure a reaction occurs at a specific speed.

New collaborative research from Northwestern University could expedite, or even eliminate, the need for scientists to manually adjust bioproduction reaction conditions at all. Using ideas conceived by graduate students across three labs, Northwestern researchers developed technology that allows microbes to produce drugs with feedback control systems, dialing down or amping up protein concentration as needed.

Implications for this research are vast. With the knowledge that microbial feedback control systems could be used more generally to produce other drugs and products, the ability for microbes to be self-regulating means other important classes of therapeutics may be newly accessible to developers.

Currently, because production pathways can be toxic to cells at certain levels, scientists have faced hurdles to engineering such microbes that leverage these pathways. But with the help of tools from the lab of Julius B. Lucks, an associate professor at the McCormick School of Engineering, this barrier may soon be nil.

"We first demonstrated our concept by making the precursor of the anti-cancer drug taxol," said Lucks, a corresponding author on the paper. "This was a great model target to try because there's challenges and complicated chemistry, but we hope the technology we developed is general in a sense, and there's a whole array of products where you'd prefer to have microbial production."

The research was published earlier this month in the journal ACS Synthetic Biology.

Synthetic biology has been a growing field over the past several decades and has entered the public sphere with the popularization of CRSPR genome editing and development of COVID-19 vaccinations with the use of engineered RNA molecules. Now in its fifth year, the Center for Synthetic Biology at Northwestern houses professors and students across majors and schools. Lucks said the center operates unlike others he's been a part of because "it's not top-down"; students are empowered to do awesome stuff.

In fact, the recently published research was formulated at a 2016 conference that two graduate students from different labs affiliated with the Center happened to attend. Cameron Glasscock, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington, was then working toward his Ph.D. in the Lucks lab. He remembers having an idea that he could use switches to enhance the microbial production of important drug compounds. When he met Bradley Biggs, a graduate student from associate engineering professor Keith Tyo's lab, in a seminar at the conference, they spent the rest of the day conspiring in the back of the room. By the end of the day, the two had an idea.

"Cameron and I knew there wasn't a high cost to trying, even if we failed," said Biggs, an author on the paper. "Ultimately, the process was easy since our labs don't really have any barriers to collaboration."

The students worked behind the scenes with undergraduate researchers to gather preliminary data that would ultimately help shape their grant proposal, then presented the data to Lucks. Excited, Lucks immediately contacted Tyo and Danielle Tullman-Ercek, an associate professor of chemical and biological engineering in McCormick, to start collaborating on a new project.

"This was one of my more formative experiences in grad school because we were writing the first draft of pretty much everything," Glasscock said.

Creating a control switch for drug precursors

Interest in fine-tuning gene expression to improve system performance is a long-standing goal for synthetic biologists. Perfecting a mechanism to do so has applications ranging from chemical synthesis to advanced diagnostics and therapeutics, but scientists are limited by the burden and stress that these systems place on host cells.

The paper proposes a new regulatory motif called a switchable feedback promoter (SFP) that uses feedback response to control the timing and overall magnitude of reactions. SFPs are a promising route to achieving dynamic control of pathways because they react to stress and mitigate damage to the host cell.

After the lab's success making the precursor to taxol, a chemotherapy drug that takes 80 years to harvest from grown yew trees, the study goes on to replicate its results by making amorphadiene, a natural product involved in the synthesis of the antimalarial drug artemisinin. The researchers found by introducing microbial production into pathways, they were effectively able to inhibit or improve production of desired chemicals.

"There's a huge interest in taking this ability of microbes to make products sustainable, sustainably," Lucks said. "People can brew beer at large volumes. What if you could brew clothes? Or fuel? And sneakers? And you could do that sustainably and without petrochemicals."

This is where support from the lab of Tyo, also a corresponding author on the study, came in. His interest in sustainability allowed the team to apply long-term goals about the product cycle to the research. He hopes with the technology developed, he'll be able to use it in much more sophisticated contexts to turn waste from feedstock into chemicals.

For now, the researchers are hoping to help other companies and teams use the tech themselves to solve new problems and help advance questions of their own.

"If the Lucks lab was that hammer - with tools and the desire to solve this problem - my lab and Tullman-Ercek's labs were the nail - with our interest in sustainable production of chemicals using cells," Tyo said. "Now, there are more nails popping up that we aren't quite sure how to solve yet."

INFORMATION:

Cisgender sexual minority men and transgender women are aware of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a daily pill for HIV-negative people to prevent HIV infection, but few are currently taking it, according to researchers at Rutgers.

The study, published in the journal AIDS and Behavior, surveyed 202 young sexual minority men and transgender women - two high-priority populations for HIV prevention - to better understand why some were more likely than others to be taking PrEP.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sexual minority men are the community most impacted by HIV, making ...

Skoltech scientists in collaboration with researchers from the University of Arizona and the Los Alamos National Laboratory have developed an approach that allows power grids to return to stability fast after demand response perturbation. Their research at the crossroads of demand response, smart grids, and power grid control was published in the journal Applied Energy.

Power grids are complex systems that manage the generation, transmission and distribution of electrical power to consumers, also called loads. As it is not possible to store electrical energy along the transmission lines, grid operators must ensure, ideally at all times, the balance between production and consumption of electrical energy, i.e. the stability of power grids. While it is essential ...

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) have developed a new mathematical model for predicting how epidemics such as COVID-19 spread. This model not only accounts for individuals' varying biological susceptibility to infection but also their levels of social activity, which naturally change over time. Using their model, the team showed that a temporary state of collective immunity--which they termed "transient collective immunity"--emerged during the early, fast-paced stages of the epidemic. However, subsequent "waves," ...

BOSTON - Legislation currently under consideration in the U.S. Congress would increase regulatory oversight of certain diagnostic tests, and a new study by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and colleagues from several other institutions demonstrates that its potential impact will depend on key details in the bill's final language. This study, published in JCO Oncology Practice, offers the first evidence-based analysis of how new rules proposed for the regulation of laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) could affect health care costs in the United States.

"The idea of having more oversight of LDTs is justified," says Jochen Lennerz, MD, PhD, medical director of the MGH Center for Integrated Diagnostics (CID) and the study's senior author. ...

April 21, 2021 - Consuming a diet high in pro-inflammatory foods - including foods that contain refined carbohydrates and sugar as well as polyunsaturated fats - may be associated with increased odds of developing testosterone deficiency among men, suggests a study in The Journal of Urology®, Official Journal of the American Urological Association (AUA). The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The risk of testosterone deficiency is greatest in men who are obese and consume a refined diet that scores high on the dietary inflammatory index (DII), according to the new research by Qiu Shi, MD, Zhang Chichen, MD, and colleagues of ...

A national strategy to ensure that families have access to food could revolutionize Canada's farms, according to a new study from Simon Fraser University's Food Systems Lab. The study proposes implementing a "right to food" framework that would support the needed funding, infrastructure, and stability that can reduce losses of edible food at the farm, while creating better access to local foods for consumers.

The study, published in the journal Resources, Conservation and Recycling, looked at the reasons for on-farm losses of edible food. Approximately 14 per cent of the world's food is lost before it ever reaches store shelves. In Canada, 35.5 million metric tonnes of food are lost or wasted annually, ...

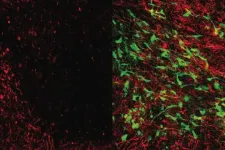

A one-time injection of an experimental stem cell therapy can repair brain damage and improve memory function in mice with conditions that replicate human strokes and dementia, a new UCLA study finds.

Dementia can arise from multiple conditions, and it is characterized by an array of symptoms including problems with memory, attention, communication and physical coordination. The two most common causes of dementia are Alzheimer's disease and white matter strokes -- small strokes that accumulate in the connecting areas of the brain.

"It's a vicious cycle: ...

We've all heard the news stories of how what you eat can affect your microbiome. Changing your diet can shift your unique microbial fingerprint. This shift can cause a dramatic effect on your health. But what about the microbiome of the plants you eat? Scientists are beginning to see how shifts in plant microbiomes also impact plant health. Unlocking the factors in plant microbial assemblage can lead to innovative and sustainable solutions to increase yield and protect our crops.

In a new study published in the Phytobiomes Journal, "Influence of plant host and organ, management strategy, and spore ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- In nature, many molecules possess a property called chirality, which means that they cannot be superimposed on their mirror images (like a left and right hand).

Chirality can influence function, impacting a pharmaceutical or enzyme's effectiveness, for example, or a compound's perceived aroma.

Now, a new study is advancing scientists' understanding of another property tied to chirality: How light interacts with chiral materials under a magnetic field.

Prior research has shown that in such a system, the left- and right-handed forms of a material absorb light differently, in ...

Plenty of people struggle to make sense of a multitude of converging voices in a crowded room. Commonly known as the "cocktail party effect," people with hearing loss find it's especially difficult to understand speech in a noisy environment.

New research suggests that, for some listeners, this may have less to do with actually discerning sounds. Instead, it may be a processing problem in which two ears blend different sounds together - a condition known as binaural pitch fusion.

The research, co-authored by scientists at Oregon Health & Science University and VA Portland Health Care System, was published today in the Journal of the Association for Research ...