New chemical tool that sheds light on how proteins recognise and interact with each other

Seeing the unseen: HKU scientists develop a new chemical tool that sheds light on how proteins recognise and interact with each other

2021-04-27

(Press-News.org) A research group led by Professor Xiang David LI from the Research Division for Chemistry and the Department of Chemistry, The University of Hong Kong, has developed a novel chemical tool for elucidating protein interaction networks in cells. This tool not only facilitates the identification of a protein's interacting partners in the complex cellular context, but also simultaneously allows the 'visualisation' of these protein-protein interactions. The findings were recently published in the prestigious scientific journal Molecular Cell.

In the human body, proteins interact with each other to cooperatively regulate essentially every biological process ranging from gene expression and signal transduction, to immune response. As a result, dysregulated protein interactions often lead to human diseases, such as cancer and Alzheimer's disease. In modern biology, it is important to comprehensively understand protein interaction networks, which has implications in disease diagnosis and can facilitate the development of treatments.

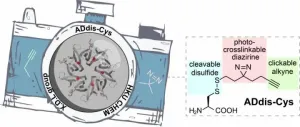

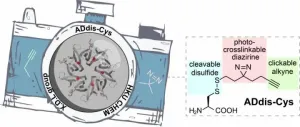

To dissect complex protein networks, two questions need to be answered: the 'who' and 'how' of protein binding. The 'who' refers to the identification of a protein's interacting partners, whereas the 'how' refers to the specific 'binding regions' that mediate these interactions. Answering these questions is challenging, as protein interactions are often too unstable and too transient to detect. To tackle this issue, Professor Li's group has previously developed a series of tools to 'trap' the protein-to-protein interactions with a chemical bond. This is possible because these tools are equipped with a special light-activated 'camera' - diazirine group that capture every binding partner of a protein when exposed to UV light. The interactions can then be examined and interpreted. Unfortunately, the 'resolution' of this 'camera' was relatively low, meaning key information about how proteins interact with each other was lost. To this end, Professor Li's group has now devised a new tool (called ADdis-Cys) that has an upgraded 'camera' to improve the 'resolution'. An alkyne handle installed next to the diazirine makes it possible to 'zoom in' to clearly see the binding regions of the proteins. Coupled with state-of-the-art mass spectrometry , ADdis-Cys is the first tool that can simultaneously identify a protein's interacting partners and pinpoint their binding regions.

In the published paper, Professor Li's lab was able to comprehensively identify many protein interactions -- some known and some newly discovered -- that are important for the regulation of essential cellular processes such as DNA replication, gene transcription and DNA damage repair. Most importantly, Professor Li's lab was able to use ADdis-Cys to reveal the binding regions mediating these protein interactions. This tool could lead to the development of chemical modulators that regulate protein interactions for treating human diseases. As a research tool, ADdis-Cys will find far-reaching applications in many areas of study, particularly in disease diagnosis and therapy.

INFORMATION:

For more information about the paper "A tri-functional amino acid enables mapping of binding sites for posttranslational modification-mediated protein-protein interactions" published in Molecular Cell, please visit: https://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/fulltext/S1097-2765(21)00268-9

For more information about Professor Xiang David Li and his research group, please visit their group's webpage: https://xianglilab.com/

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-27

The researchers in this study reached this conclusion by drawing on network modelling research and mapped the job landscapes in cities across the United States during economic crises.

Knowing and understanding which factors contribute to the health of job markets is interesting as it can help promote faster recovery after a crisis, such as a major economic recession or the current COVID pandemic. Traditional studies perceive the worker as someone linked to a specific job in a sector. However, in the real-world professionals often end up working in other sectors that require similar skills. In this sense, researchers consider job markets as being something similar to ecosystems, where organisms are linked in a complex network of interactions.

In this context, an effective job market depends ...

2021-04-27

During the Bronze Age, Mesopotamia was witness to several climate crises. In the long run, these crises prompted the development of stable forms of State and therefore elicited cooperation between political elites and non-elites. This is the main finding of a study published in the journal PNAS and authored by two scholars from the University of Bologna (Italy) and Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen (Germany).

This study investigated the impact of climate shocks in Mesopotamia between 3100 and 1750 bC. The two scholars looked at these issues through the lenses of economics and adopted a game-theory approach. They applied this approach ...

2021-04-27

A new paper on college science classes taught remotely points to teaching methods that enhance student communication and collaboration, offering a framework for enriching online instruction as the coronavirus pandemic continues to limit in-person courses.

"These varied exercises allow students to engage, team up, get outside, do important lab work, and carry out group investigations and presentations under extraordinarily challenging circumstances--and from all over the world," explains Erin Morrison, a professor in Liberal Studies at New York University and the lead author of the paper, which appears in the Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education. "The active-learning toolbox can be effectively used from ...

2021-04-27

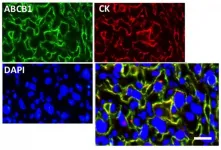

The placenta forms the interface between the maternal and foetal circulatory systems. As well as ensuring essential nutrients, endocrine and immunological signals get through to the foetus to support its development and growth, the placenta must also protect it from the accumulation of potentially toxic compounds. A study from Cécile Demarez, Mariana Astiz and colleagues at the University of Lübeck in Germany now reveals that the activity of a crucial placental gatekeeper in mice is regulated by the circadian clock, changing during the day-night cycle. The study, which has implications for the timing of maternal drug regimens, is published in the journal Development.

The circadian clock translates time-of-day information into physiological signals through rhythmic regulation ...

2021-04-27

The combined effect of rapid ocean warming and the practice of targeting big fish is affecting the viability of wild populations and global fish stock says new research by the University of Melbourne and the University of Tasmania.

Unlike earlier studies that traditionally considered fishing and climate in isolation, the research found that ocean warming and fishing combined to impact on fish recruitment, and that this took four generations to manifest.

"We found a strong decline in recruitment (the process of getting new young fish into a population) in all populations that had been exposed to warming, and this effect was highest where all the largest individuals ...

2021-04-27

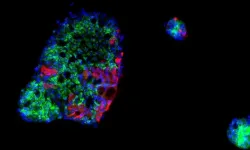

In an effort to determine the potential for COVID-19 to begin in a person's gut, and to better understand how human cells respond to SARS-CoV-2, the scientists used human intestinal cells to create organoids - 3D tissue cultures derived from human cells, which mimic the tissue or organ from which the cells originate. Their conclusions, published in the journal Molecular Systems Biology, indicate the potential for infection to be harboured in a host's intestines and reveal intricacies in the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

"Previous research had shown that SARS-CoV-2 can infect the gut," says Theodore Alexandrov, who leads one of the two EMBL groups involved. "However, it remained unclear how intestinal cells mount their immune response to the infection."

In fact, ...

2021-04-27

The building of new homes continues in flood-prone parts of England and Wales, and losses from flooding remain high. A new study, which looked at a recent decade of house building, concluded that a disproportionate number of homes built in struggling or declining neighbourhoods will end up in high flood-risk areas due to climate change.

The study, by Viktor Rözer and Swenja Surminski from the Grantham Research Institute, used property-level data for new homes and information on the socio-economic development of neighbourhoods to analyse spatial clusters ...

2021-04-27

Ship movements on the world's oceans dropped in the first half of 2020 as Covid-19 restrictions came into force, a new study shows.

Researchers used a satellite vessel-tracking system to compare ship and boat traffic in January to June 2020 with the same period in 2019.

The study, led by the University of Exeter (UK) and involving the Balearic Islands Coastal Observing and Forecasting System and the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies (both in Spain), found decreased movements in the waters off more than 70 per cent of countries.

Global ...

2021-04-27

A study led by scientists at the American Museum of Natural History has resolved a long-standing controversy about an extinct "horned" crocodile that likely lived among humans in Madagascar. Based on ancient DNA, the research shows that the horned crocodile was closely related to "true" crocodiles, including the famous Nile crocodile, but on a separate branch of the crocodile family tree. The study, published today in the journal Communications Biology, contradicts the most recent scientific thinking about the horned crocodile's evolutionary relationships and also suggests that the ancestor of modern crocodiles likely originated in Africa.

"This crocodile was hiding out on the island of Madagascar during the time when people were building ...

2021-04-27

A research group at the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research (BDR) has discovered molecular events that determine whether cancer cells live or die. With this knowledge, they found that reduced consumption of a specific protein building block prevents the growth of cells that become cancerous. These findings were published in the scientific journal eLife and open up the possibility of dietary therapy for cancer.

A tumor is a group of cancer cells that multiplies--or proliferates--uncontrollably. Tumors originate from single cells that become cancerous when genes that cause cells to proliferate are over-activated. However, because these genes, called oncogenes, often also cause cell death, activation of a single oncogene within a cell is not enough for it to become a cancer cell. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New chemical tool that sheds light on how proteins recognise and interact with each other

Seeing the unseen: HKU scientists develop a new chemical tool that sheds light on how proteins recognise and interact with each other