(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

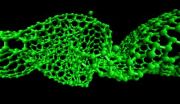

Compression causes nanotubes to buckle and twist and eventually to lose atoms from their lattice-like structure.

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A pipefitter knows how to make an exact cut on a metal rod. But it's far harder to imagine getting a precise cut on a carbon nanotube, with a diameter 1/50,000th the thickness of a human hair.

In a paper published this month in the British journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A, researchers at Brown University and in Korea document for the first time how single-walled carbon nanotubes are cut, a finding that could lead to producing more precise, higher-quality nanotubes. Such manufacturing improvements likely would make the nanotubes more attractive for use in automotive, biomedicine, electronics, energy, optics and many other fields.

"We can now design the cutting rate and the diameters we want to cut," said Kyung-Suk Kim, professor of engineering in the School of Engineering at Brown and the corresponding author on the paper.

The basics of carbon nanotube manufacturing are known. Single-atom thin graphene sheets are immersed in solution (usually water), causing them to look like a plate of tangled spaghetti. The jumbled bundle of nanotubes is then blasted by high-intensity sound waves that create cavities (or partial vacuums) in the solution. The bubbles that arise from these cavities expand and collapse so violently that the heat in each bubble's core can reach more than 5,000 degrees Kelvin, close to the temperature on the surface of the sun. Meanwhile, each bubble compresses at an acceleration 100 billion times greater than gravity. Considering the terrific energy involved, it's hardly surprising that the tubes come out at random lengths. Technicians use sieves to get tubes of the desired length. The technique is inexact partly because no one was sure what caused the tubes to fracture.

Materials scientists initially thought the super-hot temperatures caused the nanotubes to tear. A group of German researchers proposed that it was the sonic boomlets caused by collapsing bubbles that pulled the tubes apart, like a rope tugged so violently at each end that it eventually rips.

Kim, Brown postdoctoral researcher Huck Beng Chew, and engineers at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology decided to investigate further. They crafted complex molecular dynamics simulations using an array of supercomputers to tease out what caused the carbon nanotubes to break. They found that rather than being pulled apart, as the German researchers had thought, the tubes were being compressed mightily from both ends. This caused a buckling in a roughly five-nanometer section along the tubes called the compression-concentration zone. In that zone, the tube is twisted into alternating 90-degree-angle folds, so that it fairly resembles a helix.

That discovery still did not explain fully how the tubes are cut. Through more computerized simulations, the group learned the mighty force exerted by the bubbles' sonic booms caused atoms to be shot off the tube's lattice-like foundation like bullets from a machine gun.

"It's almost as if an orange is being squeezed, and the liquid is shooting out sideways," Kim said. "This kind of fracture by compressive atom ejection has never been observed before in any kind of materials."

The team confirmed the computerized simulations through laboratory tests involving sonication and electron microscopy of single-walled carbon nanotubes.

The group also learned that cutting single-walled carbon nanotubes using sound waves in water creates multiple kinks, or bent areas, along the tubes' length. The kinks are "highly attractive intramolecular junctions for building molecular-scale electronics," the researchers wrote.

INFORMATION:

Huck Beng Chew, a postdoctoral researcher in Brown's School of Engineering, is the first author on the paper. Myoung-Woon Moon and Kwang Ryul Lee, from the Korea Institute of Science and Technology, contributed to the research. The U.S. National Science Foundation and the Korea Institute of Science and Technology funded the work.

How do you cut a nanotube? Lots of compression

2010-12-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

K-State research looks at pathogenic attacks on host plants

2010-12-18

MANHATTAN, KAN. -- Two Kansas State University researchers focusing on rice genetics are providing a better understanding of how pathogens take over a plant's nutrients.

Their research provides insight into ways of reducing crop losses or developing new avenues for medicinal research.

Frank White, professor of plant pathology, and Ginny Antony, postdoctoral fellow in plant pathology, are co-authors, in partnership with researchers at three other institutions, of an article in a recent issue of the journal Nature. The article, "Sugar transporters for intercellular exchange ...

Study reveals major shift in how eczema develops

2010-12-18

Like a fence or barricade intended to stop unwanted intruders, the skin serves as a barrier protecting the body from the hundreds of allergens, irritants, pollutants and microbes people come in contact with every day. In patients with eczema, or atopic dermatitis, the most common inflammatory human skin disease, the skin barrier is leaky, allowing intruders – pollen, mold, pet dander, dust mites and others – to be sensed by the skin and subsequently wreak havoc on the immune system.

While the upper-most layer of the skin – the stratum corneum – has been pinned as the ...

Ancient raindrops reveal a wave of mountains sent south by sinking Farallon plate

2010-12-18

50 million years ago, mountains began popping up in southern British Columbia. Over the next 22 million years, a wave of mountain building swept (geologically speaking) down western North America as far south as Mexico and as far east as Nebraska, according to Stanford geochemists. Their findings help put to rest the idea that the mountains mostly developed from a vast, Tibet-like plateau that rose up across most of the western U.S. roughly simultaneously and then subsequently collapsed and eroded into what we see today.

The data providing the insight into the mountains ...

Computer games and science learning

2010-12-18

Computer games and simulations are worthy of future investment and investigation as a way to improve science learning, says LEARNING SCIENCE: COMPUTER GAMES, SIMULATIONS, AND EDUCATION, a new report from the National Research Council. The study committee found promising evidence that simulations can advance conceptual understanding of science, as well as moderate evidence that they can motivate students for science learning. Research on the effectiveness of games designed for science learning is emerging, but remains inconclusive, the report says.###

The report is available ...

You only live once: our flawed understanding of risk helps drive financial market instability

2010-12-18

Our flawed understanding of how decisions in the present restrict our options in the future means that we may underestimate the risk associated with investment decisions, according to new research by Dr Ole Peters from Imperial College London. The research, published today in the journal Quantitative Finance, suggests how policy makers might reshape financial risk controls to reduce market instability and the risk of market collapse.

Investors know that there are myriad possibilities for how a financial market might develop. Before making an investment, they try to capture ...

Efficient phosphorus use by phytoplankton

2010-12-18

Rapid turnover and remodelling of lipid membranes could help phytoplankton cope with nutrient scarcity in the open ocean.

A team led by Patrick Martin of the National Oceanography Centre has shown that a species of planktonic marine alga can rapidly change the chemical composition of its cell membranes in response to changes in nutrient supply. The findings indicate that the process may be important for nutrient cycling and the population dynamics of phytoplankton in the open ocean.

Tiny free-floating algae called phytoplankton exist in vast numbers in the upper ocean. ...

Effect of college on volunteering greatest among disadvantaged college graduates

2010-12-18

Sociologists have long known that a college education improves the chances that an individual will volunteer as an adult. Less clear is whether everyone who goes to college gets the same boost in civic engagement from the experience.

In an innovative study that compared the volunteering rates of college graduates with those of non–college graduates with similar social backgrounds and high school achievement levels, UCLA sociologist Jennie Brand found something striking: A college education has a much greater impact on volunteering rates among individuals from underprivileged ...

Ion channel responsible for pain identified by UB neuroscientists

2010-12-18

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- University at Buffalo neuroscience researchers conducting basic research on ion channels have demonstrated a process that could have a profound therapeutic impact on pain.

Targeting these ion channels pharmacologically would offer effective pain relief without generating the side effects of typical painkilling drugs, according to their paper, published in a recent issue of The Journal of Neuroscience.

"Pain is the most common symptom of injuries and diseases, and pain remains the primary reason a person visits the doctor," says Arin Bhattacharjee, PhD, ...

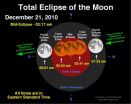

A total lunar eclipse and winter solstice coincide on Dec. 21

2010-12-18

With frigid temperatures already blanketing much of the United States, the arrival of the winter solstice on December 21 may not be an occasion many people feel like celebrating. But a dazzling total lunar eclipse to start the day might just raise a few chilled spirits.

Early in the morning on December 21 a total lunar eclipse will be visible to sky watchers across North America (for observers in western states the eclipse actually begins late in the evening of December 20), Greenland and Iceland. Viewers in Western Europe will be able to see the beginning stages of ...

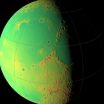

NASA's LRO creating unprecedented topographic map of moon

2010-12-18

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is allowing researchers to create the most precise and complete map to date of the moon's complex, heavily cratered landscape.

"This dataset is being used to make digital elevation and terrain maps that will be a fundamental reference for future scientific and human exploration missions to the moon," said Dr. Gregory Neumann of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "After about one year taking data, we already have nearly 3 billion data points from the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter on board the LRO spacecraft, with near-uniform ...