(Press-News.org) Forget diamonds--plastic is forever. It takes decades, or even centuries, for plastic to break down, and nearly every piece of plastic ever made still exists in some form today. We've known for a while that big pieces of plastic can harm wildlife--think of seabirds stuck in plastic six-pack rings--but in more recent years, scientists have discovered microscopic bits of plastic in the water, soil, and even the atmosphere. To learn how these microplastics have built up over the past century, researchers examined the guts of freshwater fish preserved in museum collections; they found that fish have been swallowing microplastics since the 1950s and that the concentration of microplastics in their guts has increased over time.

"For the last 10 or 15 years it's kind of been in the public consciousness that there's a problem with plastic in the water. But really, organisms have probably been exposed to plastic litter since plastic was invented, and we don't know what that historical context looks like," says Tim Hoellein, an associate professor of biology at Loyola University Chicago and the corresponding author of a new study in Ecological Applications. "Looking at museum specimens is essentially a way we can go back in time."

Caleb McMahan, an ichthyologist at the Field Museum, cares for some two million fish specimens, most of which are preserved in alcohol and stored in jars in the museum's underground Collections Resource Center. These specimens are more than just dead fish, though--they're a snapshot of life on Earth. "We can never go back to that time period, in that place," says McMahan, a co-author of the paper.

Hoellein and his graduate student Loren Hou were interested in examining the buildup of microplastics in freshwater fish from the Chicagoland region. They reached out to McMahan, who helped identify four common fish species that the museum had chronological records of dating back to 1900: largemouth bass, channel catfish, sand shiners, and round gobies. Specimens from the Illinois Natural History Survey and University of Tennessee also filled in sampling gaps.

"We would take these jars full of fish and find specimens that were sort of average, not the biggest or the smallest, and then we used scalpels and tweezers to dissect out the digestive tracts," says Hou, the paper's lead author. "We tried to get at least five specimens per decade."

To actually find the plastic in the fishes' guts, Hou treated the digestive tracts with hydrogen peroxide. "It bubbles and fizzes and breaks up all the organic matter, but plastic is resistant to the process," she explains.

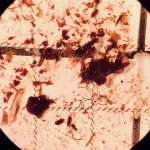

The plastic left behind is too tiny to see with the naked eye, though: "It just looks like a yellow stain, you don't see it until you put it under the microscope," says Hou. Under the magnification, though, it's easier to identify. "We look at the shape of these little pieces. If the edges are frayed, it's often organic material, but if it's really smooth, then it's most likely microplastic." To confirm the identity of these microplastics and determine where they came from, Hou and Hoellein worked with collaborators at the University of Toronto to examine the samples using Raman spectroscopy, a technique that uses light to analyze the chemical signature of a sample.

The researchers found that the amount of microplastics present in the fishes' guts rose dramatically over time as more plastic was manufactured and built up in the ecosystem. There were no plastic particles before mid-century, but when plastic manufacturing was industrialized in the 1950s, the concentrations skyrocketed.

"We found that the load of microplastics in the guts of these fishes have basically gone up with the levels of plastic production," says McMahan. "It's the same pattern of what they're finding in marine sediments, it follows the general trend that plastic is everywhere."

The analysis of the microplastics revealed an insidious form of pollution: fabrics. "Microplastics can come from larger objects being fragmented, but they're often from clothing," says Hou--whenever you wash a pair of leggings or a polyester shirt, tiny little threads break off and get flushed into the water supply.

"It's plastic on your back, and that's just not the way that we've been thinking about it," says Hoellein. "So even just thinking about it is a step forward in addressing our purchases and our responsibility."

It's not clear how ingesting these microplastics affected the fish in this study, but it's probably not great. "When you look at the effects of microplastic ingestion, especially long term effects, for organisms such as fish, it causes digestive tract changes, and it also causes increased stress in these organisms," says Hou.

While the findings are stark--McMahan described one of the paper's graphs showing the sharp rise in microplastics as "alarming"--the researchers hope it will serve as a wake-up call. "The entire purpose of our work is to contribute to solutions," says Hoellein. "We have some evidence that public education and policies can change our relationship to plastic. It's not just bad news, there's an application that I think should give everyone a collective reason for hope."

The researchers say the study also highlights the importance of natural history collections in museums. "Loren and I both love the Field Museum but don't always think about it in terms of its day-to-day scientific operations," says Hoellein. "It's an incredible resource of the natural world, not just as it exists now but as it existed in the past. It's fun for me to think of the museum collection sort of like the voice of those long dead organisms that are still telling us something about the state of the world today."

"You can't do this kind of work without these collections," says McMahan. "We need older specimens, we need the recent ones, and we're going to need what we collect in the next 100 years."

INFORMATION:

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope is giving astronomers a rare look at a Jupiter-sized, still-forming planet that is feeding off material surrounding a young star.

"We just don't know very much about how giant planets grow," said Brendan Bowler of the University of Texas at Austin. "This planetary system gives us the first opportunity to witness material falling onto a planet. Our results open up a new area for this research."

Though over 4,000 exoplanets have been cataloged so far, only about 15 have been directly imaged to date by telescopes. And the planets are so far away and small, they are simply dots in the best photos. The team's fresh technique for using Hubble to directly image this planet paves a new route for further exoplanet ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: Thirty-one new articles were published online ahead of

print for Geology in April. Topics include shocked zircon from the

Chicxulub impact crater; the Holocene Sonoran Desert; the architecture of

the Congo Basin; the southern Death Valley fault; missing water from the

Qiangtang Basin; sulfide inclusions in diamonds; how Himalayan collision

stems from subduction; ghost dune hollows; and the history of the Larsen C Ice Shelf. These Geology articles are online at END ...

The genome of single-celled plankton, known as dinoflagellates, is organized in an incredibly strange and unusual way, according to new research. The findings lay the groundwork for further investigation into these important marine organisms and dramatically expand our picture of what a eukaryotic genome can look like.

Researchers from KAUST, the U.S. and Germany have investigated the genomic organization of the coral-symbiont dinoflagellate Symbiodinium microadriaticum. The S. microadriaticum genome had already been sequenced and assembled into segments known as scaffolds but lacked a chromosome-level assembly.

The team used a technique known as Hi-C to detect ...

DURHAM, N.C. - Mantis shrimp don't need baby food. They start their life as ferocious predators who know how to throw a lethal punch.

A new study appearing April 29 in the Journal of Experimental Biology shows that larvae of the Philippine mantis shrimp (Gonodactylaceus falcatus) already display the ultra-fast movements for which these animals are known, even when they are smaller than a short grain of rice.

Their ultra-fast punching appendages measure less than 1 mm, and develop right when the larva exhausts its yolk reserves, moves away from its nest and out into the big wide sea. It immediately begins preying on organisms smaller than a grain of sand.

Although they accelerate their arms almost 100 times faster than a Formula One car, Philippine mantis shrimp larvae are slower ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Land productivity could be greatly increased by combining sheep grazing and solar energy production on the same land, according to new research by Oregon State University scientists.

This is believed to be the first study to investigate livestock production under agrivoltaic systems, where solar energy production is combined with agricultural production, such as planting agricultural crops or grazing animals.

The researchers compared lamb growth and pasture production in pastures with solar panels and traditional open pastures. They found less overall but higher quality forage in the solar pastures and that lambs raised in each pasture type ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- The Mayo Clinic data scientists who developed highly accurate computer modeling to predict trends for COVID-19 cases nationwide have new research that shows how important a high rate of vaccination is to reducing case numbers and controlling the pandemic.

Vaccination is making a striking difference in Minnesota and keeping the current level of positive cases from becoming an emergency that overwhelms ICUs and leads to more illness and death, according to a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The study, entitled "Quantifying the Importance of COVID-19 Vaccination to Our Future Outlook," outlines how Mayo's COVID-19 predictive modeling can assess future trends based on the pace of vaccination, and how vaccination trends are crucial ...

Venus is an enigma. It's the planet next door and yet reveals little about itself. An opaque blanket of clouds smothers a harsh landscape pelted by acid rain and baked at temperatures that can liquify lead.

Now, new observations from the safety of Earth are lifting the veil on some of Venus' most basic properties. By repeatedly bouncing radar off the planet's surface over the last 15 years, a UCLA-led team has pinned down the precise length of a day on Venus, the tilt of its axis and the size of its core. The findings are published today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"Venus is our sister planet, and yet these fundamental properties have remained unknown," said Jean-Luc Margot, a UCLA professor of Earth, planetary and space sciences who led the research.

Earth ...

Immunotherapies that fight cancer have been a life-saving advancement for many patients, but the approach only works on a few types of malignancies, leaving few treatment options for most cancer patients with solid tumors. Now, in two related papers published April 28, 2021 in Science Translational Medicine, researchers at UCSF have demonstrated how to engineer smart immune cells that are effective against solid tumors, opening the door to treating a variety of cancers that have long been untouchable with immunotherapies.

By "programming" basic computational abilities into immune cells that are designed to attack cancer, the researchers have overcome a number of major hurdles that have kept these strategies ...

The decision to donate to a charity is often driven by emotion rather than by calculated assessments based on how to make the biggest impact. In a review article published on April 29 in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences, researchers look at what they call "the psychology of (in)effective altruism" and how people can be encouraged to direct their charitable contributions in ways that allow them to get more bang for the buck--and help them to have a larger influence.

"In the past, most behavioral science research that's looked at charitable giving has focused on quantity and how people might be motivated to give more money to charity, or to give at all," says first author Lucius Caviola (@LuciusCaviola), a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Psychology at Harvard University. ...

Scientists in China have developed a small, flexible device that can convert heat emitted from human skin to electrical power. In their research, presented April 29 in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science, the team showed that the device could power an LED light in real time when worn on a wristband. The findings suggest that body temperature could someday power wearable electronics such as fitness trackers.

The device is a thermoelectric generator (TEG) that uses temperature gradients to generate power. In this design, researchers use the difference between the warmer body temperature and the relatively cooler ambient environment to generate power.

"This is a field with great potential," says corresponding author Qian Zhang of Harbin ...