(Press-News.org) In the early 19th century in North America, parasitic infections were quite common in urban areas due in part to population growth and urbanization. Prior research has found that poor sanitation, unsanitary privy (outhouse) conditions, and increased contact with domestic animals, contributed to the prevalence of parasitic disease in urban areas. A new study examining fecal samples from a privy on Dartmouth's campus illustrates how rural wealthy elites in New England also had intestinal parasitic infections. The findings are published in the Journal of Archeological Science: Reports.

"Our study is one of the first to demonstrate evidence of parasitic infection in an affluent rural household in the Northeast," says co-author Theresa Gildner, who was formerly the Robert A. 1925 and Catherine L. McKennan postdoctoral fellow in anthropology at Dartmouth and is currently an assistant professor of biological anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis. "Until now, there has not been a lot of evidence that parasitic disease was anywhere else other than urban areas in the early 19th century."

In June 2019, a team of Dartmouth researchers led by Jesse Casana, a professor and chair of the department of anthropology at Dartmouth, excavated a privy in front of Dartmouth's Baker-Berry Library. Earlier, an archaeological survey using ground penetrating radar instruments had identified the location as an area of particular interest. The site was home to where the Choate House once stood. Based on historical records from Rauner Special Collections Library on campus and other sources, the researchers report that the Choate House was constructed in 1786 by Sylvanus Ripley, one of the first four graduates of Dartmouth who would become a professor of divinity and a trustee at Dartmouth. In 1801, Mill Olcott, a Dartmouth graduate who became a wealthy businessman, politician and trustee, purchased the house. For several decades, Olcott and his wife and nine children lived in the house. As the study explains, the Olcotts "would have been among the wealthiest and most educated people in New England" during that time. Nearly one century later, to make space for the library in the 1920s, the Choate House was relocated to another area of Dartmouth's campus.

The Dartmouth dig revealed that the privy and its interior stone walls and contents had been well-preserved. A privy functioned not only as a toilet but also as a garbage, a place to discard food and other unwanted items. In the soil levels of the privy, the researchers found stratified deposits containing numerous artifacts from over the years, including: imported fine ceramics; peanut and coffee remains, which were considered exotic items at the time; and three fecal samples. In addition, 12 Hazard and Caswell bottles marketed to cure digestive ailments were found at the same soil level as the fecal samples, along with eight bottles of Congress & Empire Spring Co. mineral water from Saratoga Springs, N.Y., in a later soil level.

"The state of medical care during this time period was pretty terrible," explains Casana. "A lot of people probably experienced symptoms of parasitic infections but wouldn't know what was causing them. Privies would have been getting a lot of use at this time," he adds. "If people had the means, they would order special medicines to treat an upset stomach, which were really just tinctured alcohol that offered no medicinal benefits."

Gildner, whose research focuses on parasites, was out of town doing other fieldwork during the Dartmouth dig but had asked Casana to let her know if the team finds anything that resembles fecal material. To her surprise, Gildner learned that three fecal samples has been unearthed. "In studying intestinal parasites, I am used to working with fresh material-- not fecal samples that are almost 200 years old and practically dirt," says Gildner, who researched how to work with the centuries-old samples.

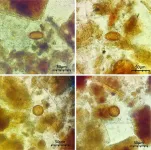

After rehydrating the fecal samples, Gildner ran them through a series of mesh sieves, from large to small, to filter out the bigger particulates and trap the small parasite eggs. The material was washed and centrifuged and slides were then prepared from each of the samples. Using a light microscope, the slides revealed that tapeworm eggs (Taenia spp.) and whipworm eggs (Trichuris trichiura) were present in each of the specimens. While the number of eggs was considered low by research standards, the parasite eggs were consistent across the three samples.

The co-authors explain that their findings are especially striking given that parasites typically prefer "warm, tropical regions" rather than the cold, snowy weather that is characteristic of New Hampshire winters, conditions which are typically thought of as inhospitable to parasite eggs.

Tapeworms are parasites that are transmitted between humans and livestock (e.g., pigs and cows). The animals consume vegetation contaminated with parasite eggs, the eggs hatch and the parasites travel to these animals' muscles. The consumption of raw or undercooked meat then leads to infection in humans. Adult tapeworms living in the intestine of the human host then lay eggs, which are passed into the environment with fecal material, starting the cycle again. Like tapeworm, whipworm eggs are passed in feces. These microscopic eggs then infect new human hosts through fecal-oral transmission (e.g., the ingestion of fecal contaminated food or water), generally due to unwashed hands and an inability to properly clean food items.

While the researchers are unable to determine if the fecal samples came from an Olcott family member, it's quite likely that all members of their household were exposed to tapeworm and whipworm. The findings demonstrate that parasite infection did not just affect urban and lower income areas, demographics which have been highlighted in previous research.

Casana says that, "I think that we take a lot of our health and infrastructure that we have today for granted. Our results show that even wealth could not protect you from these parasitic infections 200 years ago."

"Tapeworm and whipworm are still really common today in various parts of the world and can lead to nutritional deficiencies, digestive problems, and poor growth," says Gildner. "Although these infections are preventable and treatable, there's still more to be done to help prevent these infections. Access to clean water, which is essential to good hand hygiene, and sanitation are two things that many people still do not have today."

INFORMATION:

Gildner and Casana are available for comment about the study.

New research shows that patients who have had contact with the hospital due to serious glandular disease have a greater risk of subsequently developing depression. The study from iPSYCH is the largest yet to show a correlation between glandular fever and depression.

The vast majority of Danes have had glandular fever - also called mononucleosis - before adulthood. And for the vast majority of them, the disease can be cured at home with throat lozenges and a little extra care. But for some, the disease is so serious that they need to visit the hospital.

A new research result now shows that precisely those patients who have been in contact with the hospital in connection with their illness, have a greater risk of suffering a depression later.

"Our study ...

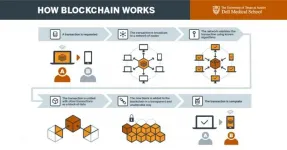

AUSTIN, Texas -- For people experiencing homelessness, missing proof of identity can be a major barrier to receiving critical services, from housing to food assistance to health care. Physical documents such as driver's licenses are highly susceptible to loss, theft or damage. However, researchers from Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin say new technology solutions such as blockchain can be used to keep important health care information secure and portable.

"Health care institutions and social services are so fragmented and siloed they're unable to accurately collect, share or verify basic identity information about a person experiencing homelessness," said Tim Mercer, M.D., MPH, director ...

A study encompassing some 9,000 dogs conducted at the University of Helsinki demonstrated that fearfulness, age, breed, the company of other members of the same species and the owner's previous experience of dogs were associated with aggressive behaviour towards humans. The findings can potentially provide tools for understanding and preventing aggressive behaviour.

Aggressive behaviour in dogs can include growling, barking, snapping and biting. These gestures are part of normal canine communication, and they also occur in non-aggressive situations, such as during play. However, aggressive behaviour ...

An extraordinary discovery in the Gulf of Eilat: Researchers from Tel Aviv University have discovered a species of ascidian, a marine animal commonly found in the Gulf of Eilat, capable of regenerating all of its organs - even if it is dissected into three fragments. The study was led by Prof. Noa Shenkar, Prof. Dorothee Huchon-Pupko, and Tal Gordon of Tel Aviv University's School of Zoology at the George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History. The findings of this surprising discovery were published in the leading journal Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.

"It is an astounding discovery, as this is an animal that belongs to the Phylum Chordata - animals with a dorsal cord - which also includes us humans," explains Prof. Noa ...

Water is a scarce resource in many of the Earth's ecosystems. This scarcity is likely to increase in the course of climate change. This, in turn, might lead to a considerable decline in plant diversity. Using experimental data from all over the world, scientists from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), and the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) have demonstrated for the first time that plant biodiversity in drylands is particularly sensitive to changes in precipitation. In an article published in Nature Communications, the team warns that this can also have consequences for the people living in the ...

The terms "co-creation" and "co-production", which denote the possibility for laypeople to participate in decision-making processes that affect their lives, have been gaining popularity. A new IIASA-led study explored options for empowering citizens as a driver for moving from awareness about the need to transform energy systems to action and participation.

The European Union's climate and energy policies for 2020-2030 require decarbonization of the energy sector. To this end, EU member countries are working on a number of key goals including greater energy efficiency, greater use of renewable energy, and increased energy security across the EU. The successful ...

In recent decades, Spain has undergone rapid social changes in terms of gender equality, despite, as a result of the Franco dictatorship, starting from a more backward position than most European countries. This process is hampered by the economic downturn that began in 2008, underlining the importance of the economic context in the development of gender inequality levels. Little attention has been paid in academia to how this gender revolution is associated with factors related to individual wellbeing.

A study by Jordi Gumà, a researcher at the Department of Political and ...

The human world is, increasingly, an urban one -- and that means elevators. Hong Kong, the hometown of physicist Zhijie Feng (Boston University),* adds new elevators at the rate of roughly 1500 every year...making vertical transport an alluring topic for quantitative research.

"Just in the main building of my undergraduate university, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology," Feng reflects, "there are 37 elevators, all numbered so we can use them to indicate the location of hundreds of classrooms. There is always a line outside each elevator lobby, and if they are shut down, we have to hike for 30 minutes."

Feng and Santa Fe Institute Professor ...

Myotonic dystrophy is a hereditary degenerative neuromuscular disease that occurs mainly in adults, affecting about 50,000 people only in Spain. Symptoms range from difficulty walking and myotonia (great difficulty in relaxing the contracted muscles) to severe neurological problems, leading to progressive disability that unfortunately puts many of those affected in a wheelchair. This disease is very heterogeneous among patients (age of onset, progression, hereditary transmission, affected muscles), which makes the development of generic treatments especially complex.

Currently, drugs against myotonic ...

LAWRENCE -- Like much of society, college athletics were thrown into disarray by the COVID-19 pandemic. While student athletes were suddenly prevented from competing, training or seeing as much of their teammates and coaches, those who perceived they were part of a positive sporting environment also coped better during the early days of the crisis, a new study from the University of Kansas has found.

KU researchers have long studied a caring, task-involved sporting climate, in which young athletes receive support and recognition for their efforts, while mistakes are treated as learning opportunities. But the pandemic provided a unique opportunity to see whether the approach helped collegiate athletes cope with the unique stresses and challenges that came with the disruption ...