Zero to hero: Overlooked material could help reduce our carbon footprint

Scientists report hitherto unobserved high-performance CO2 adsorption in zeolites at room temperature, opening doors to applications in air purification

2021-05-06

(Press-News.org) It is now well known that carbon dioxide is the biggest contributor to climate change and originates primarily from burning of fossil fuels. While there are ongoing efforts around the world to end our dependence on fossil fuels as energy sources, the promise of green energy still lies in the future. Can something be done in the meantime to reduce the concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere?

It would, in fact, be great if the CO2 in the atmosphere could simply be adsorbed! Turns out, this is exactly what direct air capture (DAC), or the capture of CO2 under ambient conditions, aims to do. However, no such material with the ability to adsorb CO2 efficiently under DAC conditions has so far been developed. "It is well known that CO2 is acidic in nature. Therefore, materials with basic nature are generally utilized as adsorbents for CO2. However, that often leads to corrosion of the system and is also not suitable for recycling the adsorbed CO2," explains Professor Yasushige Kuroda from Okayama University, Japan, who conducts research on surface chemistry.

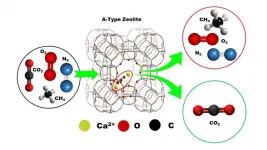

Against this backdrop, in a recent study published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A, scientists from Okayama University and Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) led by Prof. Kuroda explored the adsorption properties of a material that has so far remained an "underdog": zeolites (minerals containing mainly aluminum and silicon oxides). "Zeolite materials have received little attention as adsorbents owing to their low CO2 adsorption capacity at room temperature and in the lower pressure adsorption region, as well as their poor selectivity over nitrogen," says Prof. Kuroda.

In their study, Prof. Kuroda and his team designed an ion-exchanging method of zeolite with alkaline-earth ions and achieved a remarkably high CO2 adsorption under ambient conditions. The team specifically chose an A-type zeolite (silicon/aluminum ratio of 1) because of its appropriate pore size for adsorbing CO2, while the alkaline-earth ion exchange imparted a large electric field strength that, supposedly, acted as a driving force for the adsorption. Scientists chose a doubly charged calcium ion (Ca2+) as the exchange ion since it allowed for the greatest amount of adsorption. In fact, the adsorbed volume noted was the largest amount of CO2 to have ever been adsorbed by any zeolite system, surpassing that for other materials under similar conditions!

To investigate the underlying adsorption mechanism, the scientists carried out far-infrared (far-IR) measurements and backed them up with density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The far-IR spectra, which detected the vibrational modes due to Ca2+-zeolite vibration, showed a distinct shift towards longer wavelengths following CO2 adsorption, a feature scientists could not recognize in other samples, e.g. Na-ion exchanged A-type zeolite. They further verified their observation with a model that showed good agreement with DFT calculations.

Moreover, the scientists were able to completely desorb the adsorbed CO2 and recover the original sample and its specific adsorption properties. In addition, the sample showed a superior selective adsorption of CO2 from other gases after the scientists examined the separation of CO2 using a model gas that emulated ambient air in its composition.

The findings thus bring zeolites to the forefront as an efficient adsorbent of CO2 under ambient conditions, a feat previously thought unachievable with these systems. "Our work can open doors to potentially novel applications of zeolites, such as in the cleaning of air inside semi-closed spaces including space shuttles, submarines, and concert halls, and as an adsorbent material in the anesthetic process," speculates Prof. Kuroda excitedly.

One thing is for sure, though: chemists will never look at zeolite in the same way again.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-06

In Alzheimer's disease, neurons in the brain die. Largely responsible for the death of neurons are certain protein deposits in the brains of affected individuals: So-called beta-amyloid proteins, which form clumps (plaques) between neurons, and tau proteins, which stick together the inside of neurons. The causes of these deposits are as yet unclear. In addition, a rapidly progressive atrophy, i.e. a shrinking of the brain volume, can be observed in affected persons. Alzheimer's symptoms such as memory loss, disorientation, agitation and challenging behavior are the consequences.

Scientists at the DZNE led by Prof. Michael Wagner, head of a research group at the DZNE and senior ...

2021-05-06

Determining safe yet effective drug dosages for children is an ongoing challenge for pharmaceutical companies and medical doctors alike. A new drug is usually first tested on adults, and results from these trials are used to select doses for pediatric trials. The underlying assumption is typically that children are like adults, just smaller, which often holds true, but may also overlook differences that arise from the fact that children's organs are still developing.

Compounding the problem, pediatric trials don't always shed light on other differences that can affect recommendations for drug doses. There are many factors that limit children's participation in drug trials - for instance, some diseases simply ...

2021-05-06

AURORA, Colo. (May 6, 2021) - Scientists examining the remains of 36 bubonic plague victims from a 16th century mass grave in Germany have found the first evidence that evolutionary adaptive processes, driven by the disease, may have conferred immunity on later generations of people from the region.

"We found that innate immune markers increased in frequency in modern people from the town compared to plague victims," said the study's joint-senior author Paul Norman, PhD, associate professor in the Division of Personalized Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. "This suggests these markers might have evolved to resist the plague."

The study, done in conjunction with the Max Planck Institute in Germany, was published online Thursday in the journal Molecular ...

2021-05-06

Ultrasound is an indispensable tool for the life sciences and various industrial applications due to its non-destructive, high contrast, and high resolution qualities. A persistent challenge over the years has been how to increase the resolution of an acoustic endoscope without drastically increasing the footprint of the probe, or risking the robustness of the ultrasonic transducer. In recent years, a host of all-optical ultrasonic imaging techniques have emerged - which generally utilise pulsed lasers and optical cavities to excite and detect ultrasound waves - without sacrificing device footprint, sensitivity, or the integrity of the transducer. Thus far these powerful techniques have achieved imaging resolutions on microscopic-mesoscopic length ...

2021-05-06

Researchers at the University of Eastern Finland have discovered previously unknown non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) involved in regulating the gene expression of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF), the master regulators of angiogenesis. The study, conducted by the research groups of Associate Professor Minna Kaikkonen-Määttä and Academy Professor Seppo Ylä-Herttuala, provides a better understanding of the complex interplay of ncRNAs with gene regulation, which might open up novel therapeutic approaches in the future. The results were published in the Molecular and Cellular Biology Journal.

Over the past years, the development of next generation ...

2021-05-06

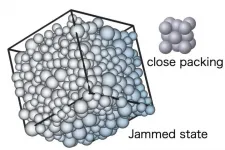

Researchers at Chinese Academy of Science and Osaka University show that, unlike the crystalline close packing of spheres, random close packing or jamming of spheres in a container can take place in a broad range of densities and anisotropies. Furthermore, they show that such diverse jammed states are all just marginally stable and exhibit common universal critical properties.

Osaka, Japan - Scientists at the theoretical institutes, Chinese Academy of Science and Cybermedia Center at Osaka University performed extensive computer simulations to generate and examine random packing of spheres. They show that the "jamming" ...

2021-05-06

A KAIST research team has developed a new technology that enables to process a large-scale graph algorithm without storing the graph in the main memory or on disks. Named as T-GPS (Trillion-scale Graph Processing Simulation) by the developer Professor Min-Soo Kim from the School of Computing at KAIST, it can process a graph with one trillion edges using a single computer.

Graphs are widely used to represent and analyze real-world objects in many domains such as social networks, business intelligence, biology, and neuroscience. As the number of graph applications increases rapidly, developing and testing new graph algorithms is becoming more important than ever before. Nowadays, many industrial ...

2021-05-06

Trust, safety and security are the most important factors affecting passengers' attitudes towards self-driving cars. Younger people felt their personal security to be significantly better than older people.

The findings are from a Finnish study into passengers' attitudes towards, and experiences of, self-driving cars. The study is also the first in the world to examine passengers' experiences of self-driving cars in winter conditions.

The findings were published in Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. The study was carried out in collaboration between the University of Eastern Finland and Tampere University.

Self-driving cars face huge expectations in Europe and the United States, which is why passengers' ...

2021-05-06

A new study has shown that most patients discharged from hospital after experiencing severe COVID-19 infection appear to return to full health, although up to a third do still have evidence of effects upon the lungs one year on.

COVID-19 has infected millions of people worldwide. People are most commonly hospitalised for COVID-19 infection when it affects the lungs - termed COVID-19 pneumonia. Whilst significant progress has been made in understanding and treating acute COVID-19 pneumonia, very little is understood about how long it takes for patients to fully recover and whether changes within the lungs persist.

In this new study, published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, researchers from the University of Southampton worked with collaborators ...

2021-05-06

Children born in December are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with a learning disorder as those born in January. ADHD was found not to affect the association between month of birth and the likelihood of a learning disability diagnosis.

The new, register based study included children born in Finland between 1996 and 2002. Of nearly 400,000 children, 3,000 were diagnosed with a specific learning disorder, for example, in reading, writing or math by the age of ten.

"We were familiar with the effects of the relative age to the general school performance, but there were no previous studies on the association between clinically diagnosed specific learning disorders and relative age, which is why we wanted to study it," says Doctoral Candidate, MD Bianca ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Zero to hero: Overlooked material could help reduce our carbon footprint

Scientists report hitherto unobserved high-performance CO2 adsorption in zeolites at room temperature, opening doors to applications in air purification