In a cell-eat-cell world calcium ions activate 'eat-me' signal in necrotic cells

2021-05-06

(Press-News.org) Just as people keep their houses clean and clutter under control, a crew of cells in the body is in charge of clearing the waste the body generates, including dying cells. The housekeeping cells remove unwanted material by a process called phagocytosis, which literally means 'eating cells.' The housekeepers engulf and ingest the dying cells and break them down to effectively eliminate them.

"Phagocytosis is very important for the body's health," said Dr. Zheng Zhou, whose lab at Baylor College of Medicine has been studying phagocytosis for many years and provided key new insights into this essential process. "When this cell-eat-cell process fails, the dying cells will lose their integrity, break down and release their content into the surrounding tissues. Dumping the cell content would cause direct tissue damage and trigger inflammatory and autoimmune responses. If the dying cells are infected by a virus, releasing the cellular content would spread the infection."

In the current study, Zhou, professor in the Verna and Marrs McLean Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Baylor, and her colleagues focused on necrosis, the type of cell death caused by injury or disease. Necrosis is mostly associated with stroke, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases and heart conditions. The team investigated in more detail the signal necrotic cells display that cues the 'eating' or phagocytic cells to engulf and eliminate the dying cell.

"In previous work, the Zhou lab showed that the signal in necrotic cells is phosphatidylserine, which is a type of lipid," said Yoshitaka Furuta, first author of the current study on which he worked while he was an undergraduate student intern in the Zhou lab. Furuta currently is a student in Baylor's Development, Disease Models and Therapeutics Graduate Program.

The team found that necrotic cells, but not living cells, expose phosphatidylserine on their outer surfaces and when phagocytes detect it, they ingest and destroy the dying cells."

Healthy cells keep phosphatidylserine in their inside, but when they are injured, for instance by lack of oxygen during a stroke when neurons are over excited due to constant entry of calcium ions, or during neurodegeneration, a process begins that ultimately flips phosphatidylserine to the outside of the cell. "We wanted to know what activates the flipping of phosphatidylserine," Furuta said.

Following the process of necrosis in the transparent worm C. elegans

The researchers worked with the model organism C. elegans, a worm that is as long as a credit card is thick. C. elegans is transparent, which allows the researchers to visually identify necrotic neurons, which look swelled when compared to living cells, and follow changes in the dynamics of cellular components using a time-lapse recording approach they developed.

Previous work in C. elegans neurons had shown that certain mutations in ion channel proteins, which regulate the flow of ions like calcium2+ in and out of the cell, induced necrosis that was accompanied by an increase of calcium ion levels inside the cell. To investigate whether changes in calcium ion levels were linked to the triggering of the eat-me signal, the team introduced some of the ion channel mutant genes in neurons of their C. elegans model and monitored both calcium levels and phosphatidylserine over time.

"We discovered in our model of necrosis that a robust and transient increase in calcium ions inside the cell preceded phosphatidylserine exposure in necrotic neurons," said Zhou, a member of Baylor's Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center. "Further experiments showed that necrotic neurons first had a small increase of calcium ions, which prompted the release of more calcium ions from an intracellular structure called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a larger source of calcium. Having larger than normal calcium levels inside the cell triggered phosphatidylserine exposure."

Supporting the role of calcium ions as a trigger of the 'eat-cell' signal, the researchers found that artificially increasing the level of calcium ions inside living cells also resulted in phosphatidylserine exposure and that suppressing calcium release from the ER prevented exposure of the signal.

The team also zoomed in into the process leading to the flipping of phosphatidylserine and found another piece of the puzzle. They discovered that a calcium increase inside the cells activates ANOH-1, an enzyme known to promote phosphatidylserine exposure.

"It was interesting to me that calcium can be good and bad for living cells," Furuta said. "Too much calcium is toxic to cells and induces necrosis, but at the same time calcium is necessary for dying cells to expose phosphatidylserine, the eat-me signal that promotes their clearance."

"Necrosis is a universal phenomenon that is present in many types of diseases and the clearance of necrotic cells is very important for keeping our bodies healthy," Zhou said.

Our findings provide new insight into the process of necrosis that can potentially lead to the development of therapeutic strategies, maybe along the lines of promoting clearance of necrotic cells by modulating phosphatidylserine exposure, which may help reduce the toxic effects of necrosis and improve cellular housekeeping."

INFORMATION:

Find all the details of this study in the journal PLoS Genetics.

Omar Pena-Ramos, Zao Li and Lucia Chiao at Baylor College of Medicine also contributed to this work.

This project was supported by NIH grants R01GM104279 and R01GM067848 and the Tobitate Ryugaku JAPAN Nihondaihyou Program.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-06

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists have developed an integrated, high-throughput system to better understand and possibly manipulate gene expression for treatment of disorders such as sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia. The research appears today in the journal Nature Genetics.

Researchers used the system to identify dozens of DNA regulatory elements that act together to orchestrate the switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin expression. The method can also be used to study other diseases that involve gene regulation.

Regulatory elements, also called genetic switches, are scattered throughout non-coding regions of DNA. ...

2021-05-06

Retinoblastoma starts in the retina, the thin membrane at the back of the eye. Most patients are infants or toddlers when their cancer is found. Without treatment, the cancer spreads. Thanks to chemotherapy, surgery and other treatments, 96% of patients survive.

St. Jude researchers studied how survivors fared years later at home and at school. A previous St. Jude study of 98 retinoblastoma survivors found that their early learning and life skills declined from diagnosis to age 5.

Researchers tested 78 of the same survivors five years later. The results were more upbeat. By age 10, almost all the children functioned within the normal range ...

2021-05-06

Asthma attacks account for almost 50 percent of the cost of asthma care which totals $80 billion each year in the United States. Asthma is more severe in Black and Hispanic/Latinx patients, with double the rates of attacks and hospitalizations as the general population.

When the COVID-19 pandemic swept over the United States, a series of reports suggested that fewer people were coming to emergency departments for all sorts of medical problems, including asthma attacks and even heart attacks. In the case of asthma, it was not clear if the drop was due to people avoiding emergency services or due to better asthma control. A new analysis from investigators at Brigham and Women's Hospital shines new light on this question. In a report of ...

2021-05-06

Vaccination dramatically reduced COVID-19 symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in St. Jude Children's Research Hospital employees compared with their unvaccinated peers, according to a research letter that appears today in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The study is among the first to show an association between COVID-19 vaccination and fewer asymptomatic infections. When the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine was authorized for use in the U.S., the vaccine was reported to be highly effective at preventing laboratory-confirmed COVID-19. Clinical trial data suggested that the two-dose regimen ...

2021-05-06

New research combines cutting-edge engineering with animal behaviour to explain the origins of efficient swimming in Nature's underwater acrobats: Seals and Sea Lions.

Seals and sea lions are fast swimming ocean predators that use their flippers to literally fly through the water. But not all seals are the same: some swim with their front flippers while others propel themselves with their back feet.

In Australia, we have fur seals and sea lions that have wing-like front flippers specialised for swimming, while in the Northern Hemisphere, grey and harbor seals have stubby, clawed paws and swim with their feet. But the reasons ...

2021-05-06

Sea turtles are known for relying on magnetic signatures to find their way across thousands of miles to the very beaches where they hatched. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on May 6 have some of the first solid evidence that sharks also rely on magnetic fields for their long-distance forays across the sea.

"It had been unresolved how sharks managed to successfully navigate during migration to targeted locations," said Save Our Seas Foundation project leader Bryan Keller, also of Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory. "This research supports the theory that they use the earth's magnetic field to help them find their way; it's nature's GPS."

Researchers ...

2021-05-06

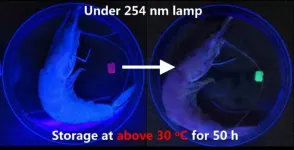

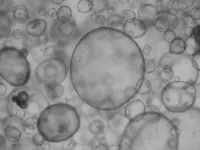

Scientists in China and Germany have designed an artificial color-changing material that mimics chameleon skin, with luminogens (molecules that make crystals glow) organized into different core and shell hydrogel layers instead of one uniform matrix. The findings, published May 6 in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science, demonstrate that a two-luminogen hydrogel chemosensor developed with this design can detect seafood freshness by changing color in response to amine vapors released by microbes as fish spoils. The material may also be used to advance the development of stretchable electronics, dynamic camouflaging robots, and anticounterfeiting technologies.

"This novel core-shell layout does not require a careful choice of luminogen pairs, nor does it require an ...

2021-05-06

Mini-organs or organoids play a big role in the future of medicine. Their countless applications can help develop and implement tailored therapies for each patient. The revolutionary development of organoids started in Utrecht with a group of curious scientists. But when organoid research starting booming, confusion arose. What exactly is an organoid? Are there different types, and if so, what should they be called? A group of experts from around the world now publishes the first consensus on what is - and what is not - an organoid.

Bart Spee, Associate Professor at Utrecht University's faculty of Veterinary Medicine, is ...

2021-05-06

The "Third Pole" of the Earth, the high mountain ranges of Asia, bears the largest number of glaciers outside the polar regions. A Sino-Swiss research team has revealed the dramatic increase in flood risk that could occur across Earth's icy Third Pole in response to ongoing climate change. Focusing on the threat from new lakes forming in front of rapidly retreating glaciers, a team, led by researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, demonstrated that the related flood risk to communities and their infrastructure could almost triple. ...

2021-05-06

New research by Joseph Wu, Edgar Engelman, and colleagues at Stanford University, US has advanced an old concept to develop a new strategy to train the immune system of mice to recognize cancer cells. This work is based on the recent understanding that induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are stem cells generated from skin or blood cells through a method called reprogramming, produce a large set of antigens that have overlap to a specific type of pancreatic cancer and that these similarities can be used for potential clinical benefit.

It is well known that vaccines can be highly effective ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] In a cell-eat-cell world calcium ions activate 'eat-me' signal in necrotic cells