In soil, high microbial fluctuation leads to more carbon emissions

Modeling shows fluctuating soil microbial populations impact how much carbon is released from soil

2021-05-10

(Press-News.org) As humans, the weather where we live influences our energy consumption. In climates where weather shifts from hot summers to very cold winters, humans consume more energy since the body has to work harder to maintain temperature.

In much the same way, weather influences microbes such as bacteria and fungi in the soil. Seasonal fluctuations in soil temperature and moisture impact microbial activities that in turn impact soil carbon emissions and nutrient cycles.

Microbes consume carbon as the source of energy. As microbes increase in quantity and activities, they consume more carbon which results in more carbon emissions and vice versa.

In a modeling study published in Global Change Biology on May 10, San Diego State University ecologists found that this microbial seasonality has a significant impact on global carbon emissions and acts as a fundamental mechanism that regulates terrestrial-climate interactions and below ground soil biogeochemistry.

"When microbial colonies in the soil are in a productive phase, increasing in numbers and size, they will need more carbon to fuel their growth," said Xiaofeng Xu, global change ecologist and lead author. "When we manipulated the quantities and activities of soil microbes in simulations and observed the reciprocal changes in soil carbon, we found that when seasonal variation was removed, microbial respiratory rates went down."

By keeping the microbial population at a constant average level, carbon emissions can be reduced.

Stewards of the land could look at reducing fluctuation in soil microbial population by reducing tillage and other management practices in order to reduce soil carbon emissions, the researchers said. It can also help agricultural scientists and growers to sustain soil fertility

Using a microbial modeling framework -- CLM-Microbe (Community Land Model) -- developed in the Ecological Modeling and Integration Lab at SDSU where he studies how climate change impacts the terrestrial carbon cycle -- Xu and colleagues deployed the model on an SDSU supercomputer to reach this conclusion.

"We know soil microbes drive carbon flux -- the amount of carbon exchanged between land, ocean and atmosphere -- by producing enzymes that impact carbon flux," Xu said. "Soil carbon completes its cycle with the help of these microbes which have a hand in ultimate control of the carbon."

Different soil microbial groups play distinct roles in the carbon cycle.

"The model's ability to simulate bacterial and fungal dynamics improves our understanding of the soil microbial community's impact on the carbon cycle," said Liyuan He, first author and doctoral student at SDSU.

The finding advances soil microbial ecology and shows the ecological significance of microbial seasonality and our understanding of soil carbon storage under changing climate conditions.

The authors modeled and validated carbon fluxes observed at an individual plot scale in nine natural biomes including tropical/subtropical forest, temperate coniferous forest, temperate broadleaf forest, boreal forest, shrubland, grassland, desert, tundra, and wetland.

"This study demonstrates the need to incorporate microbial seasonality in earth system models so we can better predict climate-carbon interactions," said Chun-Ta Lai, co-author and an ecosystem ecologist at SDSU.

Next, the researchers will explore microbial seasonality and its impact on global carbon balance, given the dynamics of land use change around the world.

INFORMATION:

The SDSU researchers also collaborated with senior staff scientist Melanie Mayes at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, and meteorologist Shohei Murayama with the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Japan.

Funding sources for the study included the U.S Department of Energy Biological and Environmental Research Program and the CSU Program for Education & Research in Biotechnology.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-10

DALLAS, May 10, 2021-- Hospitalized COVID-19 patients with impaired first-phase ejection fraction were nearly 5 times more likely to die compared to patients with healthier measures of this early, often undetected sign of heart failure, according to new research published today in Hypertension, an American Heart Association journal. First-phase ejection fraction is a measure of the left ventricular ejection fraction until the time of maximal ventricular contraction.

Cardiovascular risk factors and/or disease have been recognized as COVID-19 risk factors that have a high negative impact on patient outcomes, since early in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Researchers ...

2021-05-10

DALLAS, May 10, 2021 — Managing weight, blood pressure and cholesterol in children may help protect brain function in later life, according to new research published today in the American Heart Association’s flagship journal Circulation. This is the first study to highlight that cardiovascular risk factors accumulated from childhood through mid-life may influence poor cognitive performance at midlife.

Previous research has indicated that nearly 1 in 5 people older than 60 have at least mild loss of brain function. Cognitive deficits are known to be linked with cardiovascular risk factors, ...

2021-05-10

DALLAS, May 10, 2021 — In a small study, researchers found college athletes who contracted COVID-19 rarely had cardiac complications. Most had mild COVID symptoms that did not require treatment, and in a small percentage of those with abnormal cardiac testing, there was no evidence of heart damage on special imaging tests. All athletes returned to sports without any health concerns, according to new research published today in the American Heart Association’s flagship journal Circulation.

In spring 2020, concerns about heart damage, especially inflammation, among athletes with COVID-19 led to recommendations for cardiac screening based on symptom severity before resuming training and competition. The preferred diagnostic test for heart inflammation is an MRI of the heart, ...

2021-05-10

Low levels of serotonin in the brain are seen as a possible cause of depression and many antidepressants act by blocking a protein that transports serotonin away from the nerve cells. A brain imaging study at Karolinska Institutet now shows that the average level of the serotonin transporter increased in a group of 17 individuals who recovered from depression after cognitive behavioural therapy. The results are published in the journal Translational Psychiatry.

"Our results suggest that changes to the serotonin system are part of the biology of depression and that this change is related to the episode rather than a static feature - a state rather than a trait," says the study's last author Johan Lundberg, researcher at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, ...

2021-05-10

What has fluid physics to do with the spreading of the Corona virus? Whirlpools and pandemics seem to be rather different things, certainly in terms of comfort. Yet, newest findings about epidemic spreading come from Physics professor Björn Hof and his research group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (IST Austria), who specialize in fluids and turbulent flows. When early last year Björn Hof had to cancel his scheduled visit to Wuhan, his wife's hometown, his focus abruptly shifted to epidemic spreading.

"My group normally investigates turbulent flows in pipes and channels", he explains, "Over the last 10 years we have shown that the onset of turbulence is described ...

2021-05-10

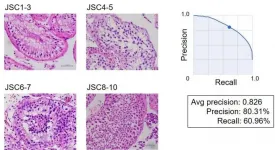

Infertility affects females and males equally. In male infertility, azoospermia (a medical condition with no sperm in semen) is a major problem that prevents a couple from having a child. For the treatment of patients with azoospermia, testicular sperm extraction (TESE) is required to obtain mature sperms. When examined, histological specimens are typically given a score, called the Johnsen score, on a scale of 1 to 10, based on the histopathological features of the testis.

"The Johnsen score has been widely used in urology since it was first reported 50 ...

2021-05-10

Researchers at Linköping University, Sweden, have made several discoveries on the functioning mechanisms of the inner hair cells of the ear, which convert sounds into nerve signals that are processed in the brain. The results, presented in the scientific journal Nature Communications, challenge the current picture of the anatomical organisation and workings of the hearing organ, which has prevailed for decades. A deeper understanding of how the hair cells are stimulated by sound is important for such matters as the optimisation of hearing aids and cochlear implants for people with hearing loss.

In ...

2021-05-10

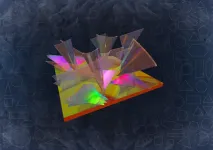

In 1884, Edwin Abbott wrote the novel Flatland: A Romance in Many Dimensions as a satire of Victorian hierarchy. He imagined a world that existed only in two dimensions, where the beings are 2D geometric figures. The physics of such a world is somewhat akin to that of modern 2D materials, such as graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides, which include tungsten disulfide (WS2), tungsten diselenide (WSe2), molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) and molybdenum diselenide (MoSe2).

Modern 2D materials consist of single-atom layers, where electrons can move ...

2021-05-10

UK landowners and conservationists welcome wider-spread use of Gene Conservation Units (GCUs) to help protect some of the rarest plants and insects, research at the University of York has shown.

In particular the Great Yellow Bumblebee and the Mountain Ringlet Butterfly, which are at risk of further population decline, would benefit from Gene Conservation Units, currently only employed for forest trees and agricultural species or their relatives.

Genetic diversity in these species is essential if they are to adapt to new, and often challenging, environmental conditions. Gene Conservation Units are areas of land managed to allow the recovery of species, and maintain evolutionary processes to enable them to adapt to environmental change.

For tree species, ...

2021-05-10

FRANKFURT. When the SARS-CoV-2 virus mutates, this initially only means that there is a change in its genetic blueprint. The mutation may lead, for example, to an amino acid being exchanged at a particular site in a viral protein. In order to quickly assess the effect of this change, a three-dimensional image of the viral protein is extremely helpful. This is because it shows whether the switch in amino acid has consequences for the function of the protein - or for the interaction with a potential drug or antibody.

Researchers at Goethe University Frankfurt and TU Darmstadt began networking internationally from the very start of the pandemic. Their goal: to describe the three-dimensional structures ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] In soil, high microbial fluctuation leads to more carbon emissions

Modeling shows fluctuating soil microbial populations impact how much carbon is released from soil