Gem-quality diamonds are nearly pure lattices of carbon. This elemental purity gives them them their luster; but it also means they carry very little information about their ages and origins. However, some lower-grade specimens harbor imperfections in the form of tiny pockets of liquid--remnants of the more complex fluids from which the crystals evolved. By analyzing these fluids , the scientists in the new study worked out the times when different diamonds formed, and the shifting chemical conditions around them.

"It opens a window--well, let's say, even a door--to some of the really big questions" about the evolution of the deep earth and the continents, said lead author Yaakov Weiss, an adjunct scientist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, where the analyses were done, and senior lecturer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. "This is the first time we can get reliable ages for these fluids." The study was published this week in the journal Nature Communications.

Most diamonds are thought to form some 150 to 200 kilometers under the surface, in relatively cool masses of rock beneath the continents. The process may go back as far as 3.5 billion years, and probably continues today. Occasionally, they are carried upward by powerful, deep-seated volcanic eruptions called kimberlites. (Don't expect to see one erupt today; the youngest known kimberlite deposits are tens of millions of years old.)

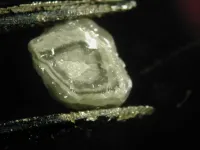

Much of what we know about diamonds comes from lab experiments, and studies of other minerals and rocks that come up with the diamonds, or are sometimes even encased within them. The 10 diamonds the team studied came from mines founded by the De Beers company in and around Kimberley, South Africa. "We like the ones that no one else really wants," said Weiss--fibrous, dirty-looking specimens containing solid or liquid impurities that disqualify them as jewelry, but carry potentially valuable chemical information. Up to now, most researchers have concentrated on solid inclusions, such as tiny bits of garnet, to determine the ages of diamonds. But the ages that solid inclusions indicate can be debatable, because the inclusions may or may not have formed at the same time as the diamond itself. Encapsulated fluids, on the other hand, are the real thing, the stuff from which the diamond itself formed.

What Weiss and his colleagues did was find a way to date the fluids. They did this by measuring traces of radioactive thorium and uranium, and their ratios to helium-4, a rare isotope that results from their decay. The scientists also figured out the maximum rate at which the nimble little helium molecules can leak out of the diamond--without which data, conclusions about ages based on the abundance of the isotope could be thrown far off. (As it turns out, diamonds are very good at containing helium.)

The team identified three distinct periods of diamond formation. These all took place within separate rock masses that eventually coalesced into present-day Africa. The oldest took place between 2.6 billion and 700 million years ago. Fluid inclusions from that time show a distinct composition, extremely rich in carbonate minerals. The period also coincided with the buildup of great mountain ranges on the surface, apparently from the collisions and squishing together of the rocks. These collisions may have had something to do with production of the carbonate-rich fluids below, although exactly how is vague, the researchers say.

The next diamond-formation phase spanned a possible time frame of 550 million to 300 million years ago, as the proto-African continent continued to rearrange itself. At this time, the liquid inclusions show, the fluids were high in silica minerals, indicating a shift in subterranean conditions. The period also coincided with another major mountain-building episode.

The most recent known phase took place between 130 million years and 85 million years ago. Again, the fluid composition switched: Now, it was high in saline compounds containing sodium and potassium. This suggests that the carbon from which these diamonds formed did not come directly from the deep earth, but rather from an ocean floor that was dragged under a continental mass by subduction. This idea, that some diamonds' carbon may be recycled from the surface, was once considered improbable, but recent research by Weiss and others has increased its currency.

One intriguing find: At least one diamond encapsulated fluid from both the oldest and youngest eras. The shows that new layers can be added to old crystals, allowing individual diamonds to evolve over vast periods of time.

It was at the end of this most recent period, when Africa had largely assumed its current shape, that a great bloom of kimberlite eruptions carried all the diamonds the team studied to the surface. The solidified remains of these eruptions were discovered in the 1870s, and became the famous De Beers mines. Exactly what caused them to erupt is still part of the puzzle.

The tiny diamond-encased droplets provide a rare way to link events that took place long ago on the surface with what was going on at the same time far below, say the scientists. "What is fascinating is, you can constrain all these different episodes from the fluids," said Cornelia Class, a geochemist at Lamont-Doherty and coauthor of the paper. "Southern Africa is one of the best-studied places in the world, but we've very rarely been able to see beyond the indirect indications of what happened there in the past."

When asked whether the findings could help geologists find new diamond deposits, Weiss just laughed. "Probably not," he said. But, he said, the method could be applied to other diamond-producing areas of the world, including Australia, Brazil, and northern Canada and Russia, to disentangle the deep histories of those regions, and develop new insights into how continents evolve.

"These are really big questions, and it's going to take people a long time to get at them," he said. "I will go to pension, and still not have finished that walk. But at least this gives us some new ideas about how to find out how things work."

INFORMATION:

The other authors of the study are Yael Kiro of Israel's Weizmann Institute of Science; Gisela Winckler and Steven Goldstein of Lamont-Doherty; and Jeff Harris of Scotland's University of Glasgow.

Scientist contacts:

Yaakov Weiss (Jerusalem): yakov.weiss@mail.huji.ac.il

Cornelia Class: (New York): class@ldeo.columbia.edu

Steven Goldstein (New York): steveg@ldeo.columbia.edu

More information: Kevin Krajick, Senior editor, science news, The Earth Institute kkrajick@ei.columbia.edu 212-854-9729

The Earth Institute, Columbia University mobilizes the sciences, education and public policy to achieve a sustainable earth. http://www.earth.columbia.edu.

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory is Columbia University's home for Earth science research. Its scientists develop fundamental knowledge about the origin, evolution and future of the natural world, from the planet's deepest interior to the outer reaches of its atmosphere, on every continent and in every ocean, providing a rational basis for the difficult choices facing humanity. http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu | @LamontEarth