Researchers find target to fight antibiotic resistance

Significance of molecule in bacteria was previously unknown

2021-05-11

(Press-News.org) Gram-negative bacteria are the bane of health care workers' existence.

They're one of the most dangerous organisms to become infected with--and one of the hardest to treat. But new research from the University of Georgia suggests a component of bacteria's cell walls may hold the key to crushing the antibiotic-resistant microbes.

The reason Gram-negative bacteria are difficult to kill is their double cell membranes, which create an almost impenetrable shield of protection. This shield blocks antibiotics from entering, preventing medications from doing their job of destroying the bacteria. Meanwhile, toxic molecules, known as lipopolysaccharides, on the surface of the bacteria's outer membrane provoke a potentially deadly immune response.

In the study published by PNAS, researchers at the College of Veterinary Medicine identified the molecule cardiolipin's key role in getting those toxic molecules onto the membrane surface, something that could serve as a new target for future therapeutics.

"If you ask where we're having the most trouble in the world of antibiotic resistance, it is with Gram-negative bacteria," said Stephen Trent, corresponding author of the study and a UGA Foundation Distinguished Professor of Infectious Diseases. "The implication of this finding is that without cardiolipin, bacteria can't make the outer membrane. Without that membrane, they're sensitive to antibiotics and the bacteria is toast."

Blocking transport to the cell membrane could not only make bacteria vulnerable to antibiotics, but the accumulation of their own toxic molecules within the cell also cause the bacteria's death.

Prior to the study, no one really understood cardiolipin's role in bacteria. In animals, however, it plays an integral part in making up the membrane of mitochondria, the organelles from which cells generate energy.

To determine the molecule's role in bacteria, the researchers created mutant forms of E. coli, which has multiple ways of making cardiolipin, to try to determine what purpose the lipid served in the cell. The team manipulated the enzymes responsible for building cardiolipin to see whether their disruption had any effect on the bacterium.

Those experiments showed that altering the cardiolipin production in a bacteria's cell had deadly ramifications for the bacteria. Without cardiolipin, the cell will continue to produce its toxic lipopolysaccharides but is unable to transport them to the cell surface.

"Eventually the cell will pop open. They just bust," Trent said. And without the large molecules on the cell surface, the bacteria's armor that typically would make it invulnerable to most antibiotics becomes penetrable.

"This paper is one of the first to link cardiolipin to maintaining the outer membrane of E. coli," said Martin Douglass, lead author of the paper and a doctoral student in UGA's Department of Infectious Diseases. "Future therapeutics could target aspects of this process and make Gram-negative bacteria vulnerable to antibiotics."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-11

ITHACA, N.Y. - A project based in Tanzania found significant improvements in the diversity of children's diets and food security for households after farmers learned about sustainable crop-growing methods, gender equity, nutrition and climate change from peer mentors.

The farmers experimented with practices introduced to them by Malawian farmers and Tanzanian and American scientists, decided which ones to incorporate within their own farms, and met monthly to share experiences and problem-solve.

The three-year study builds on longer-term research where these environmentally-friendly farming methods, called agroecology, combined with peer-mentoring and farmers collaborating in the process, had successfully improved adult nutrition in Malawi.

"There were a lot of questions about whether ...

2021-05-11

May 11, 2021 - For patients seen at a urology clinic, patient satisfaction scores vary by insurance status - with higher scores for patients on Medicare and commercial insurance, but lower scores for those on Medicaid, reports a study in Urology Practice®, an Official Journal of the American Urological Association (AUA). The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"Our study adds to previous evidence showing patient satisfaction scores are affected by the type of insurance - not just by the quality of care provided," comments senior author Werner de Riese, MD, PhD, Chair of the Department of Urology of Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center ...

2021-05-11

Columbia Engineering/UCLA team is first to demonstrate that phase precession plays a significant role in the human brain, and links not only sequential positions, as seen in animals, but also abstract progression towards specific goals.

New York, NY--May 11, 2021-- For decades the dominant approach to understanding the brain has been to measure how many times individual neurons activate during particular behaviors. In contrast to this "rate code," a more recent hypothesis proposes that neurons signal information by changing the precise timing when they activate. One such timing code, called phase precession, is commonly observed in rodents as they navigate through spaces and is thought to form the ...

2021-05-11

WASHINGTON, May 11, 2021 -- Improved ventilation can lower the risk of transmission of the COVID-19 virus, but large numbers of decades-old public school classrooms lack adequate ventilation systems. A systematic modeling study of simple air cleaners using a box fan reported in Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, shows these inexpensive units can greatly decrease the amount of airborne virus in these spaces, if used appropriately.

A low-cost air cleaner can be easily constructed from a cardboard frame topped by an air filter and a box fan. The air filter is placed between the fan and the cardboard base. The fan is oriented so that air is drawn in from the top and forced through ...

2021-05-11

PITTSBURGH, May 11, 2021 - Patients with clinically diagnosed neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19 are six times more likely to die in the hospital than those without the neurological complications, according to an interim analysis from the Global Consortium Study of Neurologic Dysfunction in COVID-19 (GCS-NeuroCOVID).

A paper published today in JAMA Network Open presents early results of the global effort to gather information about the incidence, severity and outcomes of neurological manifestations of COVID-19 disease.

"Very early on in the pandemic, it became apparent that a good number of people who were sick enough to be hospitalized also develop neurological problems," said lead author Sherry Chou, ...

2021-05-11

What The Study Did: This global observational study included patients with COVID-19 representing 13 countries and four continents, and its findings suggest neurological manifestations are prevalent among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and associated with higher in-hospital death.

Authors: Sherry H-Y. Chou, M.D., M.Sc., of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12131)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, ...

2021-05-11

Furthering efforts to understand why potentially life-saving statins are so under-prescribed among American patients with heart disease, a new study shows that clinicians are more likely to sign a script for them earlier in the day. The new study by researchers in Penn Medicine's Nudge Unit found that patients with the very first appointments of the day were most likely to have statins prescribed, and the odds progressively fell through the morning and remained low throughout the afternoon. The study was published today in JAMA Network Open.

In recent years, researchers ...

2021-05-11

WASHINGTON, May 11, 2021 -- When trauma, illness, or injury causes significant muscle loss, reconstructive procedures for bioengineering functional skeletal muscles can fall short, resulting in permanent impairments.

Finding a synergy in the importance of biochemical signals and topographical cues, researchers from Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University, and Chonnam National University developed an efficient technique for muscle regeneration and functional restoration in injured rats. They describe results from the technique in the journal Applied Physics Reviews, from AIP Publishing.

The group expanded on a method they previously developed using muscle-specific materials derived from ...

2021-05-11

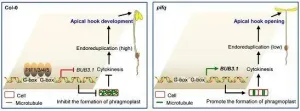

To protect their newly formed fragile organs, dark-grown dicotyledonous plants form an apical hook when penetrating through the soil. The apical hook of pifq (pif1 pif3 pif4 pif5) mutant was fully opened, even in complete darkness, suggesting that PIF proteins are required for maintaining the apical hook in the darkness and are involved in regulation of the apical hook opening. But the underlying mechanism for PIF proteins mediated apical hook development remains elusive.

To better understand how PIF proteins affect apical hook development, scientists from the Institute of Botany of the Chinese Academy of Sciences recently investigated their roles ...

2021-05-11

The Saker Falcon (Falco cherrug) is a bird of prey living in plains and forest-steppes in the West and semi-desert montane plateaus and cliffs in the East. The majority of its Central and Eastern European population is migratory and spends winters in the Mediterranean, the Near East and East Africa. With its global population estimated at 6,100-14,900 breeding pairs, the species is considered endangered according to the IUCN Red List.

In Bulgaria, the Saker Falcon, considered extinct as a breeding species since the early 2000s, was recovered in 2018 with the discovery of the first active nest from its new history in Bulgaria. The nest is built by two birds that were reintroduced back in 2015 as part of the first ever Saker Falcon reintroduction programme. The results of the 5-year programme ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers find target to fight antibiotic resistance

Significance of molecule in bacteria was previously unknown