(Press-News.org) TORONTO, ON - Geoscientists at the University of Toronto (U of T) and Istanbul Technical University have discovered a new process in plate tectonics which shows that tremendous damage occurs to areas of Earth's crust long before it should be geologically altered by known plate-boundary processes, highlighting the need to amend current understandings of the planet's tectonic cycle.

Plate tectonics, an accepted theory for over 60 years that explains the geologic processes occurring below the surface of Earth, holds that its outer shell is fragmented into continent-sized blocks of solid rock, called "plates," that slide over Earth's mantle, the rocky inner layer above the planet's core. As the plates drift around and collide with each other over million-years-long periods, they produce everything from volcanoes and earthquakes to mountain ranges and deep ocean trenches, at the boundaries where the plates collide.

Now, using supercomputer modelling, the researchers show that the plates on which Earth's oceans sit are being torn apart by massive tectonic forces even as they drift about the globe. The findings are reported in a study published this week in Nature Geoscience.

The thinking up to now focused only on the geological deformation of these drifting plates at their boundaries after they had reached a subduction zone, such as the Marianas Trench in the Pacific Ocean where the massive Pacific plate dives beneath the smaller Philippine plate and is recycled into Earth's mantle.

The new research shows much earlier damage to the drifting plate further away from the boundaries of two colliding plates, focused around zones of microcontinents - continental crustal fragments that have broken off from main continental masses to form distinct islands often several hundred kilometers from their place of origin.

"Our work discovers that a completely different part of the plate is being pulled apart because of the subduction process, and at a remarkably early phase of the tectonic cycle," said Erkan Gün, a PhD candidate in the Department of Earth Sciences in the Faculty of Arts & Science at U of T and lead author of the study.

The researchers term the mechanism a "subduction pulley" where the weight of the subducting portion that dives beneath another tectonic plate, pulls on the drifting ocean plate and tears apart the weak microcontinent sections in an early phase of potentially significant damage.

"The damage occurs long before the microcontinent fragment reaches its fate to be consumed in a subduction zone at the boundaries of the colliding plates," said Russell Pysklywec, professor and chair of the Department of Earth Sciences at U of T, and a coauthor of the study. He says another way to look at it is to think of the drifting ocean plate as an airport baggage conveyor, and the microcontinents are like pieces of luggage travelling on the conveyor.

"The conveyor system itself is actually tearing apart the luggage as it travels around the carousel, before the luggage even reaches its owner."

The researchers arrived at the results following a mysterious observation of major extension of rocks in alpine regions in Italy and Turkey. These observations suggested that the tectonic plates that brought the rocks to their current location were already highly damaged prior to the collisional and mountain-building events that normally cause deformation.

"We devised and conducted computational Earth models to investigate a process to account for the observations," said Gün. "It turned out that the temperature and pressure rock histories that we measured with the virtual Earth models match closely with the enigmatic rock evolution observed in Italy and Turkey."

According to the researchers, the findings refine some of the fundamental aspects of plate tectonics and call for a revised understanding of this fundamental theory in geoscience.

"Normally we assume - and teach - that the ocean plate conveyor is too strong to be damaged as it drifts around the globe, but we prove otherwise," said Pysklywec.

INFORMATION:

The findings build on the legacy of J. Tuzo Wilson, also a U of T scientist, and a renowned figure in geosciences who pioneered the idea of plate tectonics in the 1960s.

The research was made possible with support from SciNet and Compute Canada, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey.

Media Contacts:

Erkan Gün

Department of Earth Sciences

University of Toronto

erkan.gun@mail.utoronto.ca

Russell Pysklywec

Department of Earth Sciences

University of Toronto

russ@es.utoronto.ca

Sean Bettam

Communications + Public Affairs, Faculty of Arts & Science

University of Toronto

s.bettam@utoronto.ca

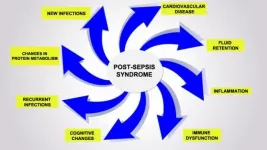

An article published in Frontiers in Immunology suggests that sepsis can cause alterations in the functioning of defense cells that persist even after the patient is discharged from hospital. This cellular reprogramming creates a disorder the authors call post-sepsis syndrome, whose symptoms include frequent reinfections, cardiovascular alterations, cognitive disabilities, declining physical functions, and poor quality of life. The phenomenon explains why so many patients who survive sepsis die sooner after hospital discharge than patients with other diseases or suffer from post-sepsis syndrome, immunosuppression ...

COVID-19 has had a significant impact since the pandemic was declared by WHO in 2020, with over 3 million deaths and counting, Researchers and medical teams have been hard at work at developing strategies to control the spread of the infection, caused by SARS-COV-2 virus and treat affected patients. Of special interest to the global population is the developments of vaccines to boost human immunity against SARS-COV-2, which are based on our understanding of how the viral proteins work during the infection in host cells. Two vaccines, namely the Pfizer/BioINtech and Oxford/AZ vaccine rely on the use of delivering the gene that encodes the viral spike protein either as an mRNA or through an adenovirus vector to promote the production of relevant antibodies. The use of monoclonal ...

In order to make meaningful gains in cardiovascular disease care, primary care medical practices should adopt a set of care improvements specific to their practice size and type, according to a new study from the national primary care quality improvement initiative EvidenceNOW. High blood pressure and smoking are among the biggest risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease. Primary care physicians help patients manage high blood pressure and provide smoking cessation interventions.

Researchers found that there is no one central playbook for all types of practices, but they did identify ...

Although new family medicine graduates intend to provide a broader scope of practice than their senior counterparts, individual family physicians' scope of practice has been decreasing, with fewer family physicians providing basic primary care services, such pediatric and prenatal care. Russell et al conducted a study to explore family medicine graduates' attitudes and perspectives on modifiable and non-modifiable factors that influenced their scope of practice and career choices. The authors conducted five focus group discussions with 32 family physicians and explored their attitudes and perspectives on their desired and actual scope of practice. Using a conceptual framework ...

In the decade since the advent of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, researchers have used the technology to delete or change genes in a growing number of cell types. Now, researchers at Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco (UCSF) have added human monocytes--white blood cells that play key roles in the immune system--to that list.

The team has adapted CRISPR-Cas9 for use in monocytes and shown the potential utility of the technology for understanding how the human immune system fights viruses and microbes. Their results were published online today in the journal Cell Reports.

"These experiments set the stage for many more studies on the interactions between major infectious diseases and human immune cells," says senior author Alex Marson, MD, PhD, director of the Gladstone-UCSF Institute ...

Pregnant women who develop severe COVID-19 infections that require hospitalization for pneumonia and other complications may not be more likely to die from these infections than non-pregnant women. In fact, they may have significantly lower death rates than their non-pregnant counterparts. That is the finding of a new study published today in the Annals of Internal Medicine conducted by researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM).

The study examined medical records from nearly 1,100 pregnant women and more than 9,800 non-pregnant patients aged 15 to 45 who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and pneumonia. Slightly less than 1 percent of the pregnant patients died from COVID-19 compared to 3.5 percent of non-pregnant patients, according to the study findings.

There ...

New York, NY--May 11, 2021--Widely used to monitor and map biological signals, to support and enhance physiological functions, and to treat diseases, implantable medical devices are transforming healthcare and improving the quality of life for millions of people. Researchers are increasingly interested in designing wireless, miniaturized implantable medical devices for in vivo and in situ physiological monitoring. These devices could be used to monitor physiological conditions, such as temperature, blood pressure, glucose, and respiration for both diagnostic and therapeutic ...

2003 was a big year for virologists. The first giant virus was discovered in this year, which shook the virology scene, revising what was thought to be an established understanding of this elusive group and expanding the virus world from simple, small agents to forms that are as complex as some bacteria. Because of their link to disease and the difficulties in defining them--they are biological entities but do not fit comfortably in the existing tree of life--viruses incite the curiosity of many people.

Scientists have long been interested in how viruses evolved, especially when it comes to giant viruses that can produce new viruses with very little help from the host--in contrast to most small viruses, which utilize the host's machinery to replicate. ...

Surgical cesarean births can expose new mothers to a range of health complications, including infection, blood clots and hemorrhage. As part of Healthy People 2020 and other maternal health objectives, the state of California exerted pressure to reduce cesarean deliveries, and statewide organizations established quality initiatives in partnership with those goals. In this study, researchers from Stanford University and the University of Chicago examined unit culture and provider mix differences on hospital and delivery units to identify characteristics of units that successfully reduced their cesarean delivery rates. The mixed-methods study surveyed ...

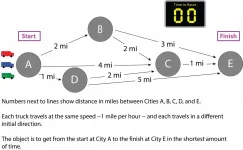

From the branching pattern of leaf veins to the variety of interconnected pathways that spread the coronavirus, nature thrives on networks -- grids that link the different components of complex systems. Networks underlie such real-life problems as determining the most efficient route for a trucking company to deliver life-saving drugs and calculating the smallest number of mutations required to transform one string of DNA into another.

Instead of relying on software to tackle these computationally intensive puzzles, researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology ...