(Press-News.org) University of Cincinnati researchers studied the teeth of prehistoric horses and bison in the Arctic to learn more about their diets compared to modern species.

What they found suggests the Arctic 40,000 years ago maintained a broader diversity of plants that, in turn, supported both more -- and more diverse -- big animals.

The Arctic today is spartan compared to the wildlife-rich landscape during the ice ages of the Pleistocene epoch between 12,000 and 2.6 million years ago when wild horses, mammoths, bison and other big animals roamed the steppes and grasslands of what is now northern Canada, northern Europe, Alaska and Siberia. Short-faced bears, ground sloths and even cave lions called the 49th State home.

The Arctic supported greater populations as well, even compared to today's spectacular herds of caribou that can number more than 750,000 animals. The area supported between six and 10 times as many large animals as today's Arctic.

"In the Pleistocene, the diversity of wildlife was so much greater than we see today," UC assistant professor Joshua Miller said. "It looked completely different. A key question is why the the Arctic so depauperate by comparison today?"

The study was published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Researchers studied two of the most common big animals living between 12,000 and 40,000 years ago in what is now Alaska: horses and steppe bison, both of which went extinct due to climate change, human hunting or a combination of both.

UC doctoral student and lead author Abigail Kelly made dental casts of fossil specimens obtained from the University of Alaska Museum and subjected the fossil teeth to dental-wear analysis to evaluate the diet of these extinct animals.

"Because foods have different textures and interact with the enamel surface in different ways, we can look at different diets," Kelly said.

Teeth of plant-eating animals show different signs of wear depending on the type of food they chew. Grass is particularly abrasive because it contains silica that can wear down teeth over time. To the naked eye, grass-eating animals have teeth with blunter wear profiles (called mesowear). When viewed with a microscope, the teeth show parallel scratches. Animals that eat less grass and more leaves from trees, herbs and shrubs have relatively sharper teeth with fewer microscopic scratches.

UC researchers found the wear patterns on the teeth of steppe bison had fewer scratches than modern plains bison that eat mostly grass but more scratches than European bison, which likely feed on more woody plants. Similarly, prehistoric horses had teeth that bore different wear patterns compared to modern horses, suggesting their diet contained fewer abrasive grasses. Prehistoric bison and horses probably ate a more varied diet rich in broadleaf herbaceous plants than today's bison and horses.But the researchers said the microwear patterns could be a reflection of the seasonal foods the animal ate in the months before it died.?

The study suggested the Arctic had a broader mix of vegetation than exists today.

"It seems like the diets of bison and horses were not that different. They were eating similarly textured foods," Miller said. "But their physiology is quite different. Bison are foregut fermenters that digest food differently compared to hindgut fermenters such as horses. So there is potential for species to get different levels of nutrition from the same food."

The study has pressing relevance for conservation of wood bison, which were hunted to extinction in the United States in the 1900s. Populations from Canada were reintroduced to Alaska in 2015. North America's largest land animal, the wood bison, is a descendant of plains bison that migrated northward about 10,000 years ago and briefly coexisted with the steppe bison before replacing them.

Biologist and study co-author Tom Seaton is overseeing the reintroduction of wood bison for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. He said their analysis offers important perspectives on how diverse populations of herbivores coexisted on the Alaska landscape thousands of years ago that could help biologists understand the needs of wood bison today.

Steppe bison survived thousands of years longer than horses, even though both relied on similar foods, according to UC's tooth analysis.

But it's likely the bison and horses evolved to use the landscape's resources in different ways -- a phenomenon called "niche partitioning." Horses and bison also have important differences in the way they digest food.

"This study provides insights for Alaska's wood bison restoration project through perspectives of niche partitioning between large herbivores on Alaska's modern landscape," Seaton said. "My hope is that this study will provide one more piece in the puzzle of bison restoration in the north."

While grazers like horses and bison went extinct in the Arctic, browsers such as moose and caribou that subsist mostly on leaves and woody plants still persist.

"What's interesting is why it's the grazers that go extinct while the browsers make it through," Miller said.

Miller has led numerous research expeditions deep into the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge by rigid inflatable boat to collect caribou antlers to track their historic migrations.

"The impacts of climate on vegetation can create a sudden shift," he said. "The cooler, drier environments of the late Pleistocene allowed megafauna to thrive. But the warm and wet climates of the Holocene led to today's wet tundra vegetation."

For her next project, doctoral student Kelly will take a closer look at bison and horses in the Yukon that lived around the same time.

"We'll be focusing on the story of how bison responded to the environmental changes of the last 50,000 years, as northern climates swung from relatively mild conditions, to extremely cold and dry during the last Glacial period, and finally rapid warming to the boreal forest climate we see today," she said. "Are bison able to change their diets in response to changing vegetation, or are they fixed within one niche?"

INFORMATION:

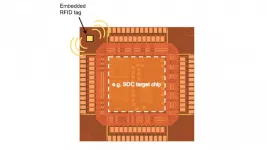

Researchers at North Carolina State University have made what is believed to be the smallest state-of-the-art RFID chip, which should drive down the cost of RFID tags. In addition, the chip's design makes it possible to embed RFID tags into high value chips, such as computer chips, boosting supply chain security for high-end technologies.

"As far as we can tell, it's the world's smallest Gen2-compatible RFID chip," says Paul Franzon, corresponding author of a paper on the work and Cirrus Logic Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at NC State.

Gen2 RFID chips are state of the art and are already in widespread use. One of the things that sets ...

Meat that is certified organic by the U.S. Department of Agriculture is less likely to be contaminated with bacteria that can sicken people, including dangerous, multidrug-resistant organisms, compared to conventionally produced meat, according to a study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The findings highlight the risk for consumers to contract foodborne illness--contaminated animal products and produce sicken tens of millions of people in the U.S. each year--and the prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms that, when they lead to illness, can complicate treatment.

The researchers found that, compared to conventionally processed meats, organic-certified meats were 56 percent less likely to be contaminated with ...

Loss of smell, or anosmia, is one of the earliest and most commonly reported symptoms of COVID-19. But the mechanisms involved had yet to be clarified. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS, Inserm, Université de Paris and the Paris Public Hospital Network (AP-HP) determined the mechanisms involved in the loss of smell in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 at different stages of the disease. They discovered that SARS-CoV-2 infects sensory neurons and causes persistent epithelial and olfactory nervous system inflammation. Furthermore, ...

Many people live with chronic pain, and in some cases, cannabis can provide relief. But the drug also can significantly impact memory and other cognitive functions. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Journal of Medicinal Chemistry have developed a peptide that, in mice, allowed Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main component of Cannabis sativa, to fight pain without the side effects.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 20% of adults in the U.S. experienced chronic pain in 2019. Opioids, the mainstay for ...

Alexandria, Va., USA -- COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in March 2020 and given an incomplete understanding of the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 at that time, the American Dental Association recommended that dental offices refrain from providing non-emergency services. As a result, 198,000 dentists in the United States closed their doors to patients. The study "Sources of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Microorganisms in Dental Aerosols," published in the Journal of Dental Research (JDR), sought to inform infection-control science by identifying the source of bacteria and viruses in aerosol generating dental procedures.

Researchers at The Ohio State University College of Dentistry, Division of Periodontology, Columbus, USA, tracked the origins of microbiota in aerosols generated during treatment ...

Are you empathic, generous and altruistic? In short, do you possess that specific personality trait defined as agreeableness in the language of psychologists? New research from SISSA recently published in the journal NeuroImage sheds light on brain mechanisms underlying this trait.

The study showed that detached and individualistic subjects seem to process information associated with social and non-social contexts in similar ways, as demonstrated by similar activation patterns in the prefrontal cortex, whereas in more agreeable subjects the activation patterns ...

Peri-implantitis, a condition where tissue and bone around dental implants becomes infected, besets roughly one-quarter of dental implant patients, and currently there's no reliable way to assess how patients will respond to treatment of this condition.

To that end, a team led by the University of Michigan School of Dentistry developed a machine learning algorithm, a form of artificial intelligence, to assess an individual patient's risk of regenerative outcomes after surgical treatments of peri-implantitis.

The algorithm is called FARDEEP, which stands for Fast and Robust Deconvolution of Expression ...

When Museums closed their doors in March 2020 for the first COVID-19 lockdown in the UK a majority moved their activities online to keep their audiences interested. Researchers from WMG, University of Warwick have worked with OUMNH, to analyse the success of the exhibitions, and say the way Museums operate will change forever.Caption: Compton Verney's homepage for the Cranach exhibition which opened in March 2020 Credit: Compton Verney

The cultural impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been analysed by researchers from WMG, University of Warwick in collaboration with OUMNH (Oxford University Museum of Natural History) who in the paper, 'Digital Responses ...

An international research team led by the University of Cologne has succeeded for the first time in connecting several atomically precise nanoribbons made of graphene, a modification of carbon, to form complex structures. The scientists have synthesized and spectroscopically characterized nanoribbon heterojunctions. They then were able to integrate the heterojunctions into an electronic component. In this way, they have created a novel sensor that is highly sensitive to atoms and molecules. The results of their research have been published under the title 'Tunneling current modulation in atomically precise graphene nanoribbon heterojunctions' in Nature Communications. The work was carried out in close cooperation between the Institute for ...

BOSTON - (May 12, 2021) - Scientists are rapidly gathering evidence that variants of gut microbiomes, the collections of bacteria and other microbes in our digestive systems, may play harmful roles in diabetes and other diseases. Now Joslin Diabetes Center scientists have found dramatic differences between gut microbiomes from ancient North American peoples and modern microbiomes, offering new evidence on how these microbes may evolve with different diets.

The scientists analyzed microbial DNA found in indigenous human paleofeces (desiccated excrement) from unusually dry caves in Utah and northern Mexico with extremely ...