(Press-News.org) What goes in must come out, a truism that now may be applied to global river networks.

Human-caused nitrogen loading to river networks is a potentially important source of nitrous oxide emission to the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change and stratospheric ozone destruction.

It happens via a microbial process called denitrification, which converts nitrogen to nitrous oxide and an inert gas called dinitrogen.

When summed across the globe, scientists report this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), river and stream networks are the source of at least 10 percent of human-caused nitrous oxide emissions to the atmosphere.

That's three times the amount estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Rates of nitrous oxide production via denitrification in small streams increase with nitrate concentrations.

"Human activities, including fossil fuel combustion and intensive agriculture, have increased the availability of nitrogen in the environment," says Jake Beaulieu of the University of Notre Dame and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Cincinnati, Ohio, and lead author of the PNAS paper.

"Much of this nitrogen is transported into river and stream networks," he says, "where it may be converted to nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, via the activity of microbes."

Beaulieu and co-authors measured nitrous oxide production rates from denitrification in 72 streams draining multiple land-use types across the United States. Their work was part of a broader cross-site study of nitrogen processing in streams.

"This multi-site experiment clearly establishes streams and rivers as important sources of nitrous oxide," says Henry Gholz, program director in NSF's Division of Environmental Biology, which funded the research.

"This is especially the case for those draining nitrogen-enriched urbanized and agricultural watersheds, highlighting the importance of managing nitrogen before it reaches open water," Gholz says. "This new global emission estimate is startling."

Atmospheric nitrous oxide concentration has increased by some 20 percent over the past century, and continues to rise at a rate of about 0.2 to 0.3 percent per year.

Beaulieu and colleagues, say the global warming potential of nitrous oxide is 300-fold greater than carbon dioxide.

Nitrous oxide accounts for some six percent of human-induced climate change, scientists estimate.

They believe that nitrous oxide is the leading human-caused threat to the atmospheric ozone layer, which protects Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.

Researchers had estimated that denitrification in river networks might be a globally important source of human-derived nitrous oxide, but the process had been poorly understood, says Beaulieu, and estimates varied widely.

While more than 99 percent of denitrified nitrogen in streams is converted to the inert gas dinitrogen rather than nitrous oxide, river networks are still leading sources of global nitrous oxide emissions, according to the new results.

"Changes in agricultural and land-use practices that result in less nitrogen being delivered to streams would reduce nitrous oxide emissions from river networks," says Beaulieu.

###

The findings, he and co-authors hope, will lead to more effective mitigation strategies.

Other authors of the paper are: Jennifer Tank of the University of Notre Dame; Stephen Hamilton of Michigan State University; Wilfred Wollheim of the University of New Hampshire; Robert Hall of the University of Wyoming; Patrick Mulholland of Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the University of Tennessee; Bruce Peterson of Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass.; Linda Ashkenas of Oregon State University; Lee Cooper of the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory in Solomons, Md.; Clifford Dahm of the University of New Mexico; Walter Dodds of Kansas State University; Nancy Grimm of Arizona State University; Sherri Johnson of the U.S. Forest Service in Corvallis, Ore.; William McDowell of the University of New Hampshire; Geoffe Poole of Montana State University; HM Valett of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; Clay Arango of Central Washington University; Melody Bernot of Ball State University; Amy Burgin of Wright State University; Chelsea Crenshaw of the University of New Mexico; Ashley Helton of the University of Georgia; Laura Johnson of Indiana University; Jonathan O'Brien of the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand; Jody Potter of the University of New Hampshire; Richard Sheibley of the University of Notre Dame and the U.S. Geological Survey in Tacoma, Washington; Daniel Sobota of Washington State University; and Suzanne Thomas of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass.

END

Increasing acidity in the sea's waters may fundamentally change how nitrogen is cycled in them, say marine scientists who published their findings in this week's issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Nitrogen is one of the most important nutrients in the oceans. All organisms, from tiny microbes to blue whales, use nitrogen to make proteins and other important compounds.

Some microbes can also use different chemical forms of nitrogen as a source of energy.

One of these groups, the ammonia oxidizers, plays a pivotal role in determining ...

VIDEO:

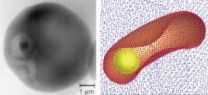

Malaria-infected red blood cells can be 50 times stiffer and have surface changes that disrupt the smooth flow of blood, depriving the brain and other organs of nutrients and oxygen....

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Although the incidence of malaria has declined in all but a few countries worldwide, according to a World Health Organization report earlier this month, malaria remains a global threat. Nearly 800,000 people ...

More effective risk-adjusted chemotherapy and sophisticated patient monitoring helped push cure rates to nearly 88 percent for older adolescents enrolled in a St. Jude Children's Research Hospital acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treatment protocol and closed the survival gap between older and younger patients battling the most common childhood cancer.

A report online in the December 20 edition of the Journal of Clinical Oncology noted that overall survival jumped 30 percent in the most recent treatment era for ALL patients who were age 15 through 18 when their cancer ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, has increased by more than 20 percent over the last century, and nitrogen in waterways is fueling part of that growth, according to a Michigan State University study.

Based on this new study, the role of rivers and streams as a source of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere now appears to be twice as high as estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, according to Stephen Hamilton, a professor at MSU's Kellogg Biological Station. The study appears in the current issue of the Proceedings of the Academy ...

VIDEO:

A new breathing therapy reduces panic and anxiety by reversing hyperventilation. The breakthrough "CART " treatment, developed by SMU psychologist Alicia E. Meuret, worked better than traditional cognitive therapy at altering...

Click here for more information.

A new treatment program teaches people who suffer from panic disorder how to reduce the terrorizing symptoms by normalizing their breathing.

The method has proved better than traditional cognitive ...

Menthol cigarettes may be harder to quit, particularly for some teens and African-Americans, who have the highest menthol cigarette use, according to a study by a team of researchers.

Recent studies have consistently found that racial/ethnic minority smokers of menthol cigarettes have a lower quit rate than comparable smokers of regular cigarettes, particularly among younger smokers.

One possible reason suggested in the report is that the menthol effect is influenced by economic factors -- less affluent smokers are more affected by price increases, forcing them to consume ...

In research published today, scientists have studied human brain samples to isolate a set of proteins that accounts for over 130 brain diseases. The paper also shows an intriguing link between diseases and the evolution of the human brain.

Brain diseases are the leading cause of medical disability in the developed world according to the World Health Organisation and the economic costs in the USA exceeds $300 billion.

The brain is the most complex organ in the body with millions of nerve cells connected by billions of synapses. Within each synapse is a set of proteins, ...

About 580 million years ago, life on Earth began a rapid period of change called the Cambrian Explosion, a period defined by the birth of new life forms over many millions of years that ultimately helped bring about the modern diversity of animals. Fossils help palaeontologists chronicle the evolution of life since then, but drawing a picture of life during the 3 billion years that preceded the Cambrian Period is challenging, because the soft-bodied Precambrian cells rarely left fossil imprints. However, those early life forms did leave behind one abundant microscopic fossil: ...

Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. – The nucleus of a cell, which houses the cell's DNA, is also home to many structures that are not bound by a membrane but nevertheless exist as distinct compartments. A team of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) scientists has discovered that the formation of one of these nuclear subcompartments, called paraspeckles, is triggered by a pair of RNA molecules, which also maintain its structural integrity.

As reported in a study published online ahead of print on December 19 in Nature Cell Biology, the scientists discovered this unique structure-building ...

the growing popularity of barbecue across the U.S. in 2010 has boosted sales and distribution, announces Sadler's Smokehouse, Ltd., North America's leader in premium, pit-smoked meats. Retail and club distribution has increased to more than 7,000 stores, and year-to-date sales of brisket, dinners and other Sadler's products are up 15 percent in this channel.

Traditionally a regional favorite in the south, smoked brisket is gaining popularity throughout the U.S. as consumers from coast to coast are adding it to their weekly menus. To meet the demand, the company has ...