(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Researchers with the BrainGate collaboration have, for the first time, used an implanted sensor to record the brain signals associated with handwriting, and used those signals to create text on a computer in real time.

In a study published in the journal Nature, a clinical trial participant with cervical spinal cord injury used the system to "type" words on a computer at a rate of 90 characters per minute, more than double the previous record for typing with a brain-computer interface. This was done by the participant merely thinking about the hand motions involved in creating written letters.

The research team is hopeful that such a system could one day help to restore people's ability to communicate following paralysis caused by injury or illness.

The new study is part of the BrainGate clinical trial, directed by Dr. Leigh Hochberg. Hochberg is a critical care neurologist and a professor at Brown University's School of Engineering and Carney Institute for Brain Science. Frank Willett, a research scientist at Stanford University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), led the study, which was supervised by Krishna Shenoy, a Stanford professor and HHMI investigator, and Dr. Jaimie Henderson, a professor of neurosurgery at Stanford.

"An important mission of our BrainGate consortium research is to restore rapid, intuitive communication for people with severe speech or motor impairments," said Hochberg, who also directs the Center for Neurotechnology and Neurorecovery at Massachusetts General Hospital and the VA RR&D Center for Neurorestoration and Neurotechnology at the Dept. of Veterans Affairs Providence Healthcare System. "Frank's demonstration of fast, accurate neural decoding of handwriting marks an exciting new chapter in the development of clinically useful neurotechnologies."

The BrainGate collaboration has been working for several years on systems that enable people to generate text through direct brain control. Previous incarnations have involved trial participants thinking about the motions involved in pointing to and clicking letters on a virtual keyboard. That system enabled one participant to type 40 characters per minute, which was the previous record speed.

For this latest study, the team wanted to find out if asking a participant to think about motions involved in writing letters and words by hand would be faster.

"We want to find new ways of letting people communicate faster," Willett said. "This new system uses both the rich neural activity recorded by intracortical electrodes and the power of language models that, when applied to the neurally decoded letters, can create rapid and accurate text."

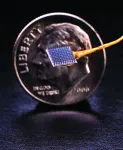

The trial participant, a 65-year-old (at the time of the study) man, was paralyzed from the neck down by a spinal cord injury. As part of the clinical trial, Henderson placed two tiny electrodes about the size of a baby aspirin in a part of his brain associated with the movement of his right arm and hand. Using signals the sensors picked up from individual neurons when the man imagined writing, a machine learning algorithm recognized the patterns his brain produced with each letter. With this system, the man could copy sentences and answer questions at a rate similar to that of someone the same age typing on a smartphone.

The system is so fast because each letter elicits a highly distinctive activity pattern, making it relatively easy for the algorithm to distinguish one from another, Willett says.

The new research is the latest in a series of advances in brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) made by the BrainGate collaboration, which includes researchers from Brown University, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, the Providence VA Medical Center, Stanford University, and Case Western Reserve University.

In 2012, the team published landmark research in which clinical trial participants were able, for the first time, to operate multidimensional robotic prosthetics using a BCI. That work has been followed by a steady stream of refinements to the system, as well as new clinical breakthroughs that have enabled people to directly control tablet apps and even move their own paralyzed limbs. Most recently, the team demonstrated the first human use of a wireless intracortical BCI that can transmit neural data at full bandwidth.

Hochberg said he's grateful to clinical trial participants for making these breakthroughs and future ones possible.

"The people who enroll in the BrainGate trial are amazing," Hochberg said. "It's their pioneering spirit that not only allows us to gain new insights into human brain function, but that leads to the creation of systems that will help other people with paralysis."

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the NIH

BRAIN Initiative (UH2NS095548, U01NS098968), the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R01DC009899, U01DC017844, R01DC014034), Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (A2295R, N2864C), L. and P. Garlick, S. and B. Reeves, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford and the Simons Foundation Collaboration on the Global Brain (543045).

Scientists have for the first time revealed the structure surrounding important receptors in the brain's hippocampus, the seat of memory and learning.

The study, carried out at Oregon Health & Science University, published today in the journal Nature.

The new study focuses on the organization and function of glutamate receptors, a type of neurotransmitter receptor involved in sensing signals between nerve cells in the hippocampus region of the brain. The study reveals the molecular structure of three major complexes of glutamate receptors in the hippocampus.

The findings may be immediately useful in drug development for conditions such as epilepsy, said senior author Eric Gouaux, Ph.D., senior scientist in the OHSU Vollum Institute, ...

Stanford scientists' software turns 'mental handwriting' into on-screen words, sentences

Call it "mindwriting."

The combination of mental effort and state-of-the-art technology have allowed a man with immobilized limbs to communicate by text at speeds rivaling those achieved by his able-bodied peers texting on a smartphone.

Stanford University investigators have coupled artificial-intelligence software with a device, called a brain-computer interface, implanted in the brain of a man with full-body paralysis. The software was able to decode information from the BCI to quickly convert the man's thoughts about handwriting into text on a computer screen.

The man was able to write ...

What The Study Did: Researchers describe overdose deaths in San Francisco before and after the initial COVID-19 shelter-in-place order to try to make clear whether characteristics of fatal overdoses changed during this time in an effort to guide future prevention efforts.

Authors: Luke N. Rodda, Ph.D., of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for the city and county of San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10452)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, ...

What The Study Did: Rates of preterm birth and stillbirth in Ontario, Canada, during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic are evaluated in this study.

Authors: Andrea N. Simpson, M.D., M.Sc., of St Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, in Toronto, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10104)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed this ...

What The Study Did: This survey study estimated the number of children and adolescents in the United States who have received medical care as a result of assault, abuse or exposure to violence.

Authors: David Finkelhor, Ph.D., of the University of New Hampshire in Durham, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9250)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and ...

What The Study Did: Researchers used registry data to examine the number, characteristics and outcomes of patients with sunburns severe enough to warrant admission to specialist burn services in Australia and New Zealand.

Authors: Lincoln M. Tracy, Ph.D., of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1110)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, ...

What The Study Did: Delayed localized injection-site reactions to the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for 16 patients are described in this report.

Authors: Alicia J. Little, M.D., Ph.D., of the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1214)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict ...

HOUSTON - The mitochondrial enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) plays an important and previously unknown role in blocking a form of cell death called ferroptosis, according to a new study published today in Nature by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Preclinical findings suggest that targeting DHODH can restore ferroptosis-driven cell death, pointing to new therapeutic strategies that may be used to induce ferroptosis and inhibit tumor growth.

"By understanding ferroptosis and how cells defend against it, we can develop therapeutic strategies to block those defense mechanisms and trigger cell death," said senior author Boyi Gan, Ph.D., associate professor of Experimental ...

LA JOLLA, CALIF. - May 12, 2021 - Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute have taken a deep dive into a previously overlooked family of proteins and discovered that they are essential to maintaining the energy that cells need to grow and survive. The proteins, known as lipid kinases, produce messengers that help balance cellular metabolism and promote overall health. The findings, published in Developmental Cell, provide further support to pursue lipid kinases as promising therapeutic targets for diseases that demand excess energy, such as cancer.

"Cancer cells are hungry--they grow faster than most cell types and need energy to support their aggressive attempts to metastasize," says Brooke Emerling, Ph.D., assistant professor in the ...

Social anxiety disorder can cause considerable suffering in children and adolescents and, for many with the disorder, access to effective treatment is limited. Researchers at Centre for Psychiatry Research at Karolinska Institutet and Region Stockholm in Sweden have now shown that internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy is an efficacious and cost-effective treatment option. The study is published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

Social anxiety disorder (SAD, previously known as social phobia) has a typical onset during childhood and is characterised by an intense and persistent fear of being scrutinised and negatively evaluated in social or performance situations.

The fear typically leads to avoidance of such anxiety triggering situations or are endured under great ...