(Press-News.org) A new discovery led by Princeton University could upend our understanding of how electrons behave under extreme conditions in quantum materials. The finding provides experimental evidence that this familiar building block of matter behaves as if it is made of two particles: one particle that gives the electron its negative charge and another that supplies its magnet-like property, known as spin.

"We think this is the first hard evidence of spin-charge separation," said Nai Phuan Ong, Princeton's Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics and senior author on the paper published this week in the journal Nature Physics.

The experimental results fulfill a prediction made decades ago to explain one of the most mind-bending states of matter, the quantum spin liquid. In all materials, the spin of an electron can point either up or down. In the familiar magnet, all of the spins uniformly point in one direction throughout the sample when the temperature drops below a critical temperature.

However, in spin liquid materials, the spins are unable to establish a uniform pattern even when cooled very close to absolute zero. Instead, the spins are constantly changing in a tightly coordinated, entangled choreography. The result is one of the most entangled quantum states ever conceived, a state of great interest to researchers in the growing field of quantum computing.

To describe this behavior mathematically, Nobel prize-winning Princeton physicist Philip Anderson (1923-2020), who first predicted the existence of spin liquids in 1973, proposed an explanation: in the quantum regime an electron may be regarded as composed of two particles, one bearing the electron's negative charge and the other containing its spin. Anderson called the spin-containing particle a spinon.

In this new study, the team searched for signs of the spinon in a spin liquid composed of ruthenium and chlorine atoms. At temperatures a fraction of a Kelvin above absolute zero (or roughly -452 degrees Fahrenheit) and in the presence of a high magnetic field, ruthenium chloride crystals enter the spin liquid state.

Graduate student Peter Czajka and Tong Gao, Ph.D. 2020, connected three highly sensitive thermometers to the crystal sitting in a bath maintained at temperatures close to absolute zero degrees Kelvin. They then applied the magnetic field and a small amount of heat to one crystal edge to measure its thermal conductivity, a quantity that expresses how well it conducts a heat current. If spinons were present, they should appear as an oscillating pattern in a graph of the thermal conductivity versus magnetic field.

The oscillating signal they were searching for was tiny -- just a few hundredths of a degree change -- so the measurements demanded an extraordinarily precise control of the sample temperature as well as careful calibrations of the thermometers in the strong magnetic field.

The team used the purest crystals available, ones grown at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) under the leadership of David Mandrus, materials science professor at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, and Stephen Nagler, director of ORNL's quantum condensed matter division. The ORNL team has extensively studied the quantum spin liquid properties of ruthenium chloride.

In a series of experiments conducted over nearly three years, Czajka and Gao detected temperature oscillations consistent with spinons with increasingly higher resolution, providing evidence that the electron is composed of two particles consistent with Anderson's prediction.

"People have been searching for this signature for four decades," Ong said, "If this finding and the spinon interpretation are validated, it would significantly advance the field of quantum spin liquids."

Czajka and Gao spent last summer confirming the experiments while under COVID restrictions that required them to wear masks and maintain social distancing.

"From the purely experimental side," Czajka said, "it was exciting to see results that in effect break the rules that you learn in elementary physics classes."

INFORMATION:

The experiments were performed in collaboration with Max Hirschberger, Ph.D. 2017 now at the University of Tokyo, Arnab Banerjee at Purdue University and ORNL, David Mandrus and Paula Lempen-Kelley at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville and ORNL, and Jiaqiang Yan and Stephen E. Nagler at ORNL. Funding at Princeton was provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation also supported the crystal growth program at the University of Tennessee.

The study, "Oscillations of the thermal conductivity in the spin-liquid state of α-RuCl3," by Peter Czajka, Tong Gao, Max Hirschberger, Paula Lampen-Kelley, Arnab Banerjee, Jiaqiang Yan, David G. Mandrus, Stephen E. Nagler and N. P. Ong, was published in the journal Nature Physics online on May 13, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41567-021-0124.

The chemical compound glyphosate, the world's most widely used herbicide, can weaken the immune systems of insects, suggests a study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Glyphosate is the active ingredient in Round Up™, a popular U.S. brand of weed killer products.

The researchers investigated the effects of glyphosate on two evolutionarily distant insects, Galleria mellonella, the greater wax moth, and Anopheles gambiae, a mosquito that is an important transmitter of malaria to humans in Africa. They found that ...

People who work nontraditional work hours, such as 11 p.m.-7 p.m., or the "graveyard" shift, are more likely than people with traditional daytime work schedules to develop a chronic medical condition -- shift work sleep disorder -- that disrupts their sleep. According to researchers at the University of Missouri, people who develop this condition are also three times more likely to be involved in a vehicle accident.

"This discovery has many major implications, including the need to identify engineering counter-measures to help prevent these crashes from happening," said Praveen Edara, department chair and professor of civil and environmental ...

Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, a trio of science communication researchers proposes to treat the Covid-19 misinformation "infodemic" with the same methods used to halt epidemics.

"We believe the intertwining spreads of the virus and of misinformation and disinformation require an approach to counteracting deceptions and misconceptions that parallels epidemiologic models by focusing on three elements: real-time surveillance, accurate diagnosis, and rapid response," the authors write in a Perspective article.

"The word 'communicable' comes from the Latin communicare, ...

New research led by the University of Kent has found that people fail to recognise the role of factory farming in causing infectious diseases.

The study published by Appetite demonstrates that people blame wild animal trade or lack of government preparation for epidemic outbreaks as opposed to animal agriculture and global meat consumption.

Scientists forewarned about the imminence of global pandemics such as Covid-19, but humankind failed to circumvent its arrival. They had been warning for decades about the risks of intensive farming practices for public health. The scale of production and overcrowded conditions on factory farms make it easy for viruses to migrate and spread. Furthermore, ...

HOUSTON - Cytokine-activated natural killer (NK) cells derived from donated umbilical cord blood, combined with an investigational bispecific antibody targeting CD16a and CD30 known as AFM13, displayed potent anti-tumor activity against CD30+ lymphoma cells, according to a new preclinical study from researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The findings were published today in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. These results led to the launch of a Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the combination of cord blood-derived NK cells (cbNK cells) with AFM13 as an experimental cell-based immunotherapy in patients with CD30+ lymphoma.

"Developing novel NK cell therapies has been a priority for my ...

WASHINGTON -- In a new study, researchers have shown that 3D printing can be used to make highly precise and complex miniature lenses with sizes of just a few microns. The microlenses can be used to correct color distortion during imaging, enabling small and lightweight cameras that can be designed for a variety of applications.

"The ability to 3D print complex micro-optics means that they can be fabricated directly onto many different surfaces such as the CCD or CMOS chips used in digital cameras," said Michael Schmid, a member of the research team from University of Stuttgart in Germany. "The micro-optics can ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Free from human disturbance for a century, an inland island in Central America has nevertheless lost more than 25% of its native bird species since its creation as part of the Panama Canal's construction, and scientists say the losses continue.

The Barro Colorado Island extirpations show how forest fragmentation can reduce biodiversity when patches of remnant habitat lack connectivity, according to a study by researchers at Oregon State University.

Even when large remnants of forest are protected, some species still fail to survive because of subtle ...

DALLAS - May 12, 2021 - Scientists with UT Southwestern's Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute have identified the molecular mechanism that can cause weight gain for those using a common antipsychotic medication. The findings, published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, suggest new ways to counteract the weight gain, including a drug recently approved to treat genetic obesity, according to the study, which involved collaborations with scientists at UT Dallas and the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology.

"If this effect can be shown in clinical trials, it could give us a way to effectively treat ...

Astronomers commonly refer to massive stars as the chemical factories of the Universe. They generally end their lives in spectacular supernovae, events that forge many of the elements on the periodic table. How elemental nuclei mix within these enormous stars has a major impact on our understanding of their evolution prior to their explosion. It also represents the largest uncertainty for scientists studying their structure and evolution.

A team of astronomers led by May Gade Pedersen, a postdoctoral scholar at UC Santa Barbara's Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, have now measured the internal mixing within an ensemble of these stars using observations ...

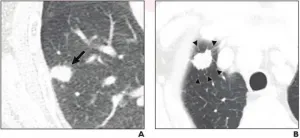

Leesburg, VA, May 13, 2021--According to an open-access Editor's Choice article in ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), CT features may help identify which patients with stage IA non-small cell lung cancer are optimal candidates for sublobar resection, rather than more extensive surgery.

This retrospective study included 904 patients (453 men, 451 women; mean age, 62 years) who underwent lobectomy (n=574) or sublobar resection (n=330) for stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Two thoracic radiologists independently evaluated findings on preoperative chest CT, later resolving any discrepancies. Recurrences were identified via medical record review.

"In patients with stage IA non-small cell lung cancer, pathologic ...