(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Black people with early stage liver cancer were more likely than white patients to die from their disease, according to a new study from the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Five years after diagnosis, 18 percent of white liver cancer patients were alive but only 15 percent of Hispanic patients and 12 percent of black patients were. Median survival times ranged from 10 months for whites and Hispanics to 8 months for blacks.

The researchers also found racial and ethnic disparities in how often patients received treatment, with black and Hispanic patients less likely than whites to have any kind of treatment.

When researchers looked at survival only among patients who had been treated, the disparity in survival persisted, but the gap narrowed, especially for Hispanics. Blacks who had surgery lived a median 29 months, Hispanics 40 months and whites 43 months. Median survival for all races was only four to six months without treatment.

"Just under a third of the patients we looked at received treatment, which is a significant underuse of appropriate interventions for the most treatable stages of liver cancer," says study author Christopher J. Sonnenday, M.D., M.H.S., assistant professor of surgery at the U-M Medical School and assistant professor of health management and policy at the U-M School of Public Health.

Researchers looked at data from 13,244 patients with early stage hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver cancer. Patients were identified through the Surveillance and Epidemiology End Results registry, a database from the National Cancer Institute that collects information on cancer incidence, prevalence and survival.

Results of the study appear in the December issue of Archives of Surgery.

Liver cancer incidence is increasing, and the disease is difficult to treat in its later stages. Patients diagnosed with advanced disease have only a 5 percent chance of living five years after diagnosis. Early stage disease is more treatable, with options including tumor ablation, surgery to remove a portion of the liver or liver transplant surgery.

"Liver cancer requires highly complex care that is available only in larger referral hospitals. Our study suggests that not only do members of different racial and ethnic groups face barriers to accessing this care, but the survival of blacks and Hispanics even after receiving these treatments appears to be inferior to whites," Sonnenday says.

INFORMATION:

Liver cancer statistics: About 24,000 Americans will be diagnosed with liver cancer this year and 18,900 will die from the disease, according to the American Cancer Society

Additional authors: U-M Department of Surgery House Officers Amit K. Mathur, M.D., M.S.; Nicholas H. Osborne, M.D.; Raymond J. Lynch, M.D., M.S.; and Amir A. Ghaferi, M.D.; and Justin Dimick, M.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of surgery

Funding: National Institutes of Health

Disclosure: None

Reference: Archives of Surgery, Vol. 145, No. 12, pp. 1158-1163, Dec. 20, 2010

Resources:

U-M Cancer AnswerLine, 800-865-1125

U-M Comprehensive Cancer Center, www.mcancer.org

Clinical trials at U-M, www.UMClinicalStudies.org

Blacks with liver cancer more likely to die, study finds

Black, Hispanic patients less likely to receive treatment for early disease

2010-12-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study: Natural supplement may reduce common-cold duration by only half a day

2010-12-21

MADISON — An over-the-counter herbal treatment believed to have medicinal benefits has minimal impact in relieving the common cold, according to research by the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health.

The study, published in this month's Annals of Internal Medicine, involved echinacea, a wild flower (also known as the purple coneflower) found in meadows and prairies of the Midwestern plains. The supplement is sold in capsule form in drug and retail stores. Dried echinacea root has been used in homemade remedies such as teas, dried herb and ...

Young female chimpanzees appear to treat sticks as dolls

2010-12-21

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- The must-have gift for young female chimpanzees this holiday season might be in the Christmas tree, not under it.

That's the finding of scientists at Harvard University and Bates College, who say female chimpanzees appear to treat sticks as dolls, carrying them around until they have offspring of their own. Young males engage in such behavior much less frequently.

The new work by Sonya M. Kahlenberg and Richard W. Wrangham, described this week in the journal Current Biology, provides the first suggestive evidence of a wild non-human species playing ...

Outsmarting the wind

2010-12-21

RICHLAND, Wash. – Meteorological equipment typically used to monitor storms could help power grid operators know when to expect winds that will send turbine blades spinning, as well as help them avoid the sudden stress that spinning turbines could put on the electrical grid.

"We know that the wind will blow, but the real challenge is to know when and how much," said atmospheric scientist Larry Berg. "This project takes an interesting approach –adapting an established technology for a new use – to find a reliable way to measure winds and improve wind power forecasts."

Berg ...

CCNY-led interdisciplinary team recreates colonial hydrology

2010-12-21

Hydrologists may have a new way to study historical water conditions. By synthesizing present-day data with historical records they may be able to recreate broad hydrologic trends on a regional basis for periods from which scant data is available.

Lack of reliable historical data can impede hydrologists' understanding of the current state of waterways and their ability to make predictions about the future. That was the case for the rivers of the northeastern United States between 1600 and 1800, a period that runs from just before the first European settlers arrived ...

What makes a face look alive? Study says it's in the eyes

2010-12-21

The face of a doll is clearly not human; the face of a human clearly is. Telling the difference allows us to pay attention to faces that belong to living things, which are capable of interacting with us. But where is the line at which a face appears to be alive? A new study published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, finds that a face has to be quite similar to a human face in order to appear alive, and that the cues are mainly in the eyes.

Several movies have tried and failed to generate lifelike animations of humans. ...

Globalization burdens future generations with biological invasions

2010-12-21

A new study on biological invasions based on extensive data of alien species from 10 taxonomic groups and 28 European countries has shown that patterns of established alien species richness are more related to historical levels of socio-economic drivers than to contemporary ones. An international group of 16 researchers reported the new finding this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). The publication resulted from the three-year project DAISIE (Delivering Alien Invasive Inventory for Europe, www.europe-aliens.org), ...

New report finds Cambodia's HIV/AIDS fight at critical crossroads in funding, prevention

2010-12-21

Phnom Penh, Cambodia (21 December, 2010) – Despite Cambodia's remarkable history in driving down HIV infections, a report released today on the future of AIDS in the country argues that future success is not guaranteed and the government needs to focus increasingly on wise prevention tactics and assume more of the financing of its AIDS program.

The report, called The Long-Run Costs and Financing of HIV/AIDS in Cambodia, written by Cambodian experts working closely with staff of the Results for Development Institute (R4D), based in Washington, D.C., finds that Cambodia, ...

How often do giant black holes become hyperactive?

2010-12-21

A new study from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory tells scientists how often the biggest black holes have been active over the last few billion years. This discovery clarifies how supermassive black holes grow and could have implications for how the giant black hole at the center of the Milky Way will behave in the future.

Most galaxies, including our own, are thought to contain supermassive black holes at their centers, with masses ranging from millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun. For reasons not entirely understood, astronomers have found that these ...

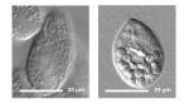

New study upends thinking about how liver disease develops

2010-12-21

In the latest of a series of related papers, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, with colleagues in Austria and elsewhere, present a new and more definitive explanation of how fibrotic cells form, multiply and eventually destroy the human liver, resulting in cirrhosis. In doing so, the findings upend the standing of a long-presumed marker for multiple fibrotic diseases and reveal the existence of a previously unknown kind of inflammatory white blood cell.

The results are published in this week's early online edition of the Proceedings ...

UCSB scientists demonstrate biomagnification of nanomaterials in simple food chain

2010-12-21

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) –– An interdisciplinary team of researchers at UC Santa Barbara has produced a groundbreaking study of how nanoparticles are able to biomagnify in a simple microbial food chain.

"This was a simple scientific curiosity," said Patricia Holden, professor in UCSB's Bren School of Environmental Science & Management and the corresponding author of the study, published in an early online edition of the journal Nature Nanotechnology. "But it is also of great importance to this new field of looking at the interface of nanotechnology and the environment."

Holden's ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

Electric field tunes vibrations to ease heat transfer

Researchers find that landowner trust, experience influence feral hog management

Breaking down the battery problem

ACMG Foundation to present adaptive bikes to Baltimore-area children with genetic conditions at heartwarming “Day of Caring” event on March 13

Racial disparities in food insecurity for high- and low-income households

Incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest on a postholiday weekday

Prior authorization bans for buprenorphine alone may not improve treatment retention

When light boosts protein evolution

New model may predict preeclampsia in late pregnancy

Lifestyle medicine experts call meaning, purpose, and spirituality foundational to evidence-based, whole-person lifestyle change

Significant acceleration of global warming since 2015

FAU awarded $2.4M NIH grant to study immune signaling and social behavior

Deep learning-enabled virtual multiplexed immunostaining of label-free tissue for vascular invasion assessment

New PET imaging study reveals how ketamine relieves treatment-resistant depression

New study reveals differences between anime bamboo muzzle and actual bamboo

The ‘Great Texas Freeze’ killed thousands of purple martins; biologists worry recovery could take decades

Cancer has a unique nuclear metabolic fingerprint

Tiny thermometers offer on-chip temperature monitoring for processors

New compound stops common complications after intestinal surgery

Breaking through water treatment limits with defect-free, high-efficiency next-generation ceramic filters!

Researchers determine structural motifs of water undecamer cluster

Researchers enhance photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance of covalent organic frameworks by constitutional isomer strategy

Molecular target drives immunogenicity in cancer immunotherapy

[Press-News.org] Blacks with liver cancer more likely to die, study findsBlack, Hispanic patients less likely to receive treatment for early disease