(Press-News.org) In the latest of a series of related papers, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, with colleagues in Austria and elsewhere, present a new and more definitive explanation of how fibrotic cells form, multiply and eventually destroy the human liver, resulting in cirrhosis. In doing so, the findings upend the standing of a long-presumed marker for multiple fibrotic diseases and reveal the existence of a previously unknown kind of inflammatory white blood cell.

The results are published in this week's early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In all types of chronic diseases, healthy, functioning tissues are progressively replaced by fibrous scarring, which renders the tissues or larger organ increasingly dysfunctional until, eventually, it fails. The process is called fibrosis. In the human liver, the end result is cirrhosis, the 12th leading cause of death by disease in the United States with roughly 27,000 deaths annually. Fibrosis occurs in other organs as well, such as the heart, kidneys and lungs, with comparable deadly effect.

Scientists do not fully understand the process of fibrosis, particularly how problematic fibroblast cells are created. For years, conventional wisdom has posited that fibroblasts are likely to be transformed epithelial cells, a conversion called "epithelial to mesenchymal transition" or EMT. A protein called fibroblast-specific protein 1 (FSP1) has long been considered to be a reliable indicator of fibroblasts in injured organs undergoing tissue remodeling and has been broadly used to identify the presence of fibrotic disease.

The new research undermines the validity of prevailing assumptions about EMT and FSP1, but also opens the door to new avenues of investigation that could ultimately lead to improved detection and treatment of cirrhosis and similar conditions.

"This work, along with earlier papers, puts into question a whole area of research – at least in terms of the liver" said David Brenner, MD, Vice Chancellor for Health Sciences, dean of the UC San Diego School of Medicine and co-author of the paper. "The old evidence and assumptions about the source of fibroblasts and the role of FSP1 as a marker are not valid."

Specifically, in experiments using cell cultures, human liver samples and mouse models, the researchers found no evidence of EMT – that transformed epithelial cells became liver fibroblasts. Rather, endogenous stellate cells appear to be the culprit, though the scientists note many types of cells seem to contribute, directly or indirectly, to liver fibrosis.

Likewise, experiments proved FSP1 to be an unreliable marker for fibrosis. Cells containing FSP1 increased in human and experimental liver disease and in liver cancer, but researchers found that liver fibroblasts do not express the protein, nor do hepatic stellate cells – a major cell type involved in liver fibrosis. Similarly, FSP1 was determined not to be a marker for myofibroblasts (a fibroblast with some properties of a smooth muscle cell) or any precursors of myofibroblasts.

"There have been hundreds of papers based on FSP1 as a marker," said Brenner. "That thinking now seems to have been a mistake. One of the take-home messages of this paper is that FSP1 clearly can't be reliably used as a marker."

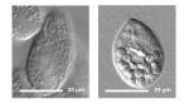

On the other hand, the scientists discovered that FSP1 is a consistent marker for a previously unknown subset of inflammatory white blood cells or macrophages found in injured livers. The protein appears to also perform biological functions in the macrophages, though these remain to be determined.

"It's a whole new class of monocytes," said Brenner. "We don't know what they do, but they're worth investigating."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the study are Christoph H. Osterreicher of the Department of Medicine, Laboratory of Gene Regulation and Signal Transduction and Department of Pharmacology, all at UC San Diego, and of the Institute of Pharmacology, Center for Physiology and Pharmacology and the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology at Medical University of Vienna in Austria; Melitta Penz-Osterreicher of the Department of Medicine at UC San Diego and the Department of Internal Medicine III, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Medical University of Vienna; Sergei I. Grivennikov and Monica Guma of the Laboratory of Gene Regulation and Signal Transduction, Department of Pharmacology, UC San Diego; Ekaterina K. Koltsova of the Division of Inflammation Biology, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology; Christian Datz of the Department of Internal Medicine, General Hospital Oberndorf in Austria; Roman Sasik and Gary Hardiman of Biomedical Genomics Microarray Facility, Department of Medicine, UC San Diego; and Michael Karin of the Laboratory of Gene Regulation and Signal Transduction, Department of Pharmacology at UC San Diego.

New study upends thinking about how liver disease develops

2010-12-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UCSB scientists demonstrate biomagnification of nanomaterials in simple food chain

2010-12-21

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) –– An interdisciplinary team of researchers at UC Santa Barbara has produced a groundbreaking study of how nanoparticles are able to biomagnify in a simple microbial food chain.

"This was a simple scientific curiosity," said Patricia Holden, professor in UCSB's Bren School of Environmental Science & Management and the corresponding author of the study, published in an early online edition of the journal Nature Nanotechnology. "But it is also of great importance to this new field of looking at the interface of nanotechnology and the environment."

Holden's ...

New imaging advance illuminates immune response in breathing lung

2010-12-21

Fast-moving objects create blurry images in photography, and the same challenge exists when scientists observe cellular interactions within tissues constantly in motion, such as the breathing lung. In a recent UCSF-led study in mice, researchers developed a method to stabilize living lung tissue for imaging without disrupting the normal function of the organ. The method allowed the team to observe, for the first time, both the live interaction of living cells in the context of their environment and the unfolding of events in the immune response to lung injury.

The finding ...

Strange new twist: Berkeley researchers discover Möbius symmetry in metamaterials

2010-12-21

Möbius symmetry, the topological phenomenon that yields a

half-twisted strip with two surfaces but only one side, has been a source of fascination since its discovery in 1858 by German mathematician August Möbius. As artist M.C. Escher so vividly demonstrated in his "parade of ants," it is possible to traverse the "inside" and "outside" surfaces of a Möbius strip without crossing over an edge. For years, scientists have been searching for an example of Möbius symmetry in natural materials without any success. Now a team of scientists has discovered Möbius symmetry in ...

New study examines immunity in emerging species of a major mosquito carrer of malaria

2010-12-21

In notable back-to-back papers appearing in the prestigioous journal Science in October, teams of researchers, one led by Nora Besansky, a professor of biological sciences and a member of the Eck Institute for Global Health at the University of Notre Dame, provided evidence that Anopheles gambiae, which is one of the major mosquito carriers of the malaria parasite in Sub-Saharan Africa, is evolving into two separate species with different traits.

Another significant study appearing in this week's edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and ...

New study focuses on nitrogen in waterways as cause of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere

2010-12-21

Jake Beaulieu, a postdoctoral researcher the Environmental Protection Agency in Cincinnati, Ohio, who earned his doctorate at the University of Notre Dame, and Jennifer Tank, Galla Professor of Biological Sciences at the University, are lead authors of new paper demonstrating that streams and rivers receiving nitrogen inputs from urban and agricultural land uses are a significant source of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere.

Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change and the loss of the protective ozone layer. Nitrogen loading to river networks ...

The orange in your stocking: researchers squeezing out maximum health benefits

2010-12-21

VIDEO:

BYU nutritionist Tory Parker talks about his study into why oranges are so good for you.

Click here for more information.

Provo, Utah - In time for Christmas, BYU nutritionists are squeezing all the healthy compounds out of oranges to find just the right mixture responsible for their age-old health benefits.

The popular stocking stuffer is known for its vitamin C and blood-protecting antioxidants, but researchers wanted to learn why a whole orange is better for ...

Link between depression and inflammatory response found in mice

2010-12-21

Vanderbilt University researchers may have found a clue to the blues that can come with the flu – depression may be triggered by the same mechanisms that enable the immune system to respond to infection.

In a study in the December issue of Neuropsychopharmacology, Chong-Bin Zhu, M.D., Ph.D., Randy Blakely, Ph.D., William Hewlett, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues activated the immune system in mice to produce "despair-like" behavior that has similarities to depression in humans.

"Many people exhibit signs of lethargy and depressed mood during flu-like illnesses," said Blakely, ...

Boosting supply of key brain chemical reduces fatigue in mice

2010-12-21

Researchers at Vanderbilt University have "engineered" a mouse that can run on a treadmill twice as long as a normal mouse by increasing its supply of acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter essential for muscle contraction.

The finding, reported this month in the journal Neuroscience, could lead to new treatments for neuromuscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis, which occurs when cholinergic nerve signals fail to reach the muscles, said Randy Blakely, Ph.D., director of the Vanderbilt Center for Molecular Neuroscience.

Blakely and his colleagues inserted a gene into ...

Dodds contributes to new national study on nitrogen water pollution

2010-12-21

MANHATTAN, KAN. -- A Kansas State University professor is part of a national research team that discovered that streams and rivers produce three times more greenhouse gas emissions than estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Through his work on the Konza Prairie Biological Station and other local streams, Walter Dodds, university distinguished professor of biology, helped demonstrate that nitrous oxide emissions from rivers and streams make up at least 10 percent of human-caused nitrous oxide emissions -- three times greater than current estimates ...

Research shows that environmental factors limit species diversity

2010-12-21

It's long been accepted by biologists that environmental factors cause the diversity—or number—of species to increase before eventually leveling off. Some recent work, however, has suggested that species diversity continues instead of entering into a state of equilibrium. But new research on lizards in the Caribbean not only supports the original theory that finite space, limited food supplies, and competition for resources all work together to achieve equilibrium; it builds on the theory by extending it over a much longer timespan.

The research was done by Daniel Rabosky ...