(Press-News.org) It's long been accepted by biologists that environmental factors cause the diversity—or number—of species to increase before eventually leveling off. Some recent work, however, has suggested that species diversity continues instead of entering into a state of equilibrium. But new research on lizards in the Caribbean not only supports the original theory that finite space, limited food supplies, and competition for resources all work together to achieve equilibrium; it builds on the theory by extending it over a much longer timespan.

The research was done by Daniel Rabosky of the University of California, Berkeley and Richard Glor of the University of Rochester who studied patterns of species accumulation of lizards over millions of years on the four Caribbean islands of Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Cuba. Their paper is being published December 21 in the journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Glor and Rabosky focused on species diversity—the number of distinct species of lizards—not the number of individual lizards.

"Geographic size correlates to diversity," said Glor. "In general, the larger the area, the greater the number of species that can be supported. For example, there are 60 species of Anolis lizards on Cuba, but far fewer species on the much smaller islands of Jamaica and Puerto Rico." There are only 6 species on Jamaica and 10 on Puerto Rico.

Ecologists Robert MacArthur of Princeton University and E.O. Wilson of Harvard University established the theory of island biogeography in the 1960s to explain the diversity and richness of species in restricted habitats, as well as the limits on the growth in number of species. Glor said the MacArthur-Wilson theory was developed for ecological time-scales, which encompass thousands of years, while his work with Rabosky extends the concepts over a million years. "MacArthur and Wilson recognized the macroevolutionary implications of their work," explained Glor, "but focused on ecological time-scales for simplicity."

Historically, biologists needed fossil records to study patterns of species diversification of lizards on the Caribbean islands. But advances in molecular methodology allowed Glor and Rabosky to use DNA sequences to reconstruct evolutionary trees that show the relationships between species.

The two scientists found that species diversification of lizards on the four islands reached a plateau millions of years ago and has essentially come to an end.

Glor said the extent and quality of the data used in the research allowed him and Rabosky to show that species diversification of lizards on the islands was not continuing and had indeed entered a state of equilibrium.

"When we look at other islands and continents that vary in species richness," said Glor, "we can't just consider rates of accumulation; we need to look at the plateau points."

Glor emphasizes that a state of equilibrium does not mean that the evolution of a species comes to an end. Lizards will continue to adapt to changes in their environment, but they are not expected to develop in a way that increases the number of species within a habitat.

Glor believes his work with Rabosky represents the "final word" on the importance of limits on species diversity over the rate of speciation when explaining the species-area relationship in anole lizards.

INFORMATION: END

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – Less-invasive robotic surgery for upper airway and digestive track malignant tumors is as effective as other minimally invasive surgical techniques based on patient function and survival, according to University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas account for about 4 percent of malignant tumors diagnosed in the United States each year. Currently the standard minimally invasive surgery for these tumors is transoral laser microsurgery.

Previous studies have shown that the robotic surgery was better for patients ...

What goes in must come out, a truism that now may be applied to global river networks.

Human-caused nitrogen loading to river networks is a potentially important source of nitrous oxide emission to the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change and stratospheric ozone destruction.

It happens via a microbial process called denitrification, which converts nitrogen to nitrous oxide and an inert gas called dinitrogen.

When summed across the globe, scientists report this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy ...

Increasing acidity in the sea's waters may fundamentally change how nitrogen is cycled in them, say marine scientists who published their findings in this week's issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Nitrogen is one of the most important nutrients in the oceans. All organisms, from tiny microbes to blue whales, use nitrogen to make proteins and other important compounds.

Some microbes can also use different chemical forms of nitrogen as a source of energy.

One of these groups, the ammonia oxidizers, plays a pivotal role in determining ...

VIDEO:

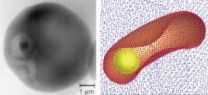

Malaria-infected red blood cells can be 50 times stiffer and have surface changes that disrupt the smooth flow of blood, depriving the brain and other organs of nutrients and oxygen....

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Although the incidence of malaria has declined in all but a few countries worldwide, according to a World Health Organization report earlier this month, malaria remains a global threat. Nearly 800,000 people ...

More effective risk-adjusted chemotherapy and sophisticated patient monitoring helped push cure rates to nearly 88 percent for older adolescents enrolled in a St. Jude Children's Research Hospital acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treatment protocol and closed the survival gap between older and younger patients battling the most common childhood cancer.

A report online in the December 20 edition of the Journal of Clinical Oncology noted that overall survival jumped 30 percent in the most recent treatment era for ALL patients who were age 15 through 18 when their cancer ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, has increased by more than 20 percent over the last century, and nitrogen in waterways is fueling part of that growth, according to a Michigan State University study.

Based on this new study, the role of rivers and streams as a source of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere now appears to be twice as high as estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, according to Stephen Hamilton, a professor at MSU's Kellogg Biological Station. The study appears in the current issue of the Proceedings of the Academy ...

VIDEO:

A new breathing therapy reduces panic and anxiety by reversing hyperventilation. The breakthrough "CART " treatment, developed by SMU psychologist Alicia E. Meuret, worked better than traditional cognitive therapy at altering...

Click here for more information.

A new treatment program teaches people who suffer from panic disorder how to reduce the terrorizing symptoms by normalizing their breathing.

The method has proved better than traditional cognitive ...

Menthol cigarettes may be harder to quit, particularly for some teens and African-Americans, who have the highest menthol cigarette use, according to a study by a team of researchers.

Recent studies have consistently found that racial/ethnic minority smokers of menthol cigarettes have a lower quit rate than comparable smokers of regular cigarettes, particularly among younger smokers.

One possible reason suggested in the report is that the menthol effect is influenced by economic factors -- less affluent smokers are more affected by price increases, forcing them to consume ...

In research published today, scientists have studied human brain samples to isolate a set of proteins that accounts for over 130 brain diseases. The paper also shows an intriguing link between diseases and the evolution of the human brain.

Brain diseases are the leading cause of medical disability in the developed world according to the World Health Organisation and the economic costs in the USA exceeds $300 billion.

The brain is the most complex organ in the body with millions of nerve cells connected by billions of synapses. Within each synapse is a set of proteins, ...

About 580 million years ago, life on Earth began a rapid period of change called the Cambrian Explosion, a period defined by the birth of new life forms over many millions of years that ultimately helped bring about the modern diversity of animals. Fossils help palaeontologists chronicle the evolution of life since then, but drawing a picture of life during the 3 billion years that preceded the Cambrian Period is challenging, because the soft-bodied Precambrian cells rarely left fossil imprints. However, those early life forms did leave behind one abundant microscopic fossil: ...