(Press-News.org) In notable back-to-back papers appearing in the prestigioous journal Science in October, teams of researchers, one led by Nora Besansky, a professor of biological sciences and a member of the Eck Institute for Global Health at the University of Notre Dame, provided evidence that Anopheles gambiae, which is one of the major mosquito carriers of the malaria parasite in Sub-Saharan Africa, is evolving into two separate species with different traits.

Another significant study appearing in this week's edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and also led by Besansky suggests that the mosquitoes' immune response to malaria parasites, mediated by a gene called "TEP1," is one of the traits that differ between the two forms of Anopheles gambiae.

Both papers have major implications for malaria controls efforts and could eventually lead to new malaria prevention efforts.

The Science papers described a painstaking genomic analysis by Besansky and an international consortium of scientists that revealed that the two varieties of Anopheles gambiae, called M and S, which Besansky describes as physically indistinguishable, are evolving into two distinct species.

In the new PNAS study, the researchers performed genome-wide comparisons of M and S to pinpoint the genetic differences that could help explain how they are adapting to different larval habitats. One of the genomic regions with the most pronounced differences between M and S contained the TEP1 gene.

The researchers report that they found a distinct resistance allele (one of two or more forms of the DNA sequence of a particular gene) of TEP1 circulating only in M mosquitoes despite the fact that M and S mosquitoes live side-by-side in many parts of Africa. The authors demonstrated that this allele confers resistance to human malaria parasites. The patterns of genetic and geographic variation in the TEP1 gene suggest that this resistance allele arose recently in M populations from West Africa, and that it is beneficial in the mosquitoes' ability to fight off pathogenic infections.

Previous research has shown that TEP1 confers broad-spectrum protection against bacteria and parasites, so resistance is not specific to malaria parasites, and may have evolved in response to entirely different pathogens found in the aquatic habitat of immature mosquitoes. The implication for malaria transmission by the adult mosquitoes is nonetheless apparent.

"On theoretical grounds, we expect that as two groups of mosquitoes begin to adapt to alternative types of habitats, aspects of their behavior and physiology will change to improve their survival in those habitats," Besansky said. "Even though none of these changes may come about as a direct consequence of infection with malaria parasites, changes in mosquito lifespan, fertility, or density that can accompany ecological adaptation will impact the mosquitoes' role in malaria transmission. Our results provide a possible example of this process.

"In the M form, we have a situation in which modifications to a key player in mosquito immunity — even if the change may have been selected in response to immune challenge at the aquatic stage — can alter the dynamics of malaria transmission by the adults. Changes in these sorts of behavioral and physiological traits between M and S also have the potential to affect the degree of mosquito exposure or its response to malaria interventions."

Besansky notes much work remains to be done to better understand the specific forces driving immune and other changes in M and S, and their impact on malaria transmission. Important, but challenging, next steps will be to study mosquito immune responses under conditions that more closely mimic those encountered in the field in natural populations. ###

The research study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

END

Jake Beaulieu, a postdoctoral researcher the Environmental Protection Agency in Cincinnati, Ohio, who earned his doctorate at the University of Notre Dame, and Jennifer Tank, Galla Professor of Biological Sciences at the University, are lead authors of new paper demonstrating that streams and rivers receiving nitrogen inputs from urban and agricultural land uses are a significant source of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere.

Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change and the loss of the protective ozone layer. Nitrogen loading to river networks ...

VIDEO:

BYU nutritionist Tory Parker talks about his study into why oranges are so good for you.

Click here for more information.

Provo, Utah - In time for Christmas, BYU nutritionists are squeezing all the healthy compounds out of oranges to find just the right mixture responsible for their age-old health benefits.

The popular stocking stuffer is known for its vitamin C and blood-protecting antioxidants, but researchers wanted to learn why a whole orange is better for ...

Vanderbilt University researchers may have found a clue to the blues that can come with the flu – depression may be triggered by the same mechanisms that enable the immune system to respond to infection.

In a study in the December issue of Neuropsychopharmacology, Chong-Bin Zhu, M.D., Ph.D., Randy Blakely, Ph.D., William Hewlett, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues activated the immune system in mice to produce "despair-like" behavior that has similarities to depression in humans.

"Many people exhibit signs of lethargy and depressed mood during flu-like illnesses," said Blakely, ...

Researchers at Vanderbilt University have "engineered" a mouse that can run on a treadmill twice as long as a normal mouse by increasing its supply of acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter essential for muscle contraction.

The finding, reported this month in the journal Neuroscience, could lead to new treatments for neuromuscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis, which occurs when cholinergic nerve signals fail to reach the muscles, said Randy Blakely, Ph.D., director of the Vanderbilt Center for Molecular Neuroscience.

Blakely and his colleagues inserted a gene into ...

MANHATTAN, KAN. -- A Kansas State University professor is part of a national research team that discovered that streams and rivers produce three times more greenhouse gas emissions than estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Through his work on the Konza Prairie Biological Station and other local streams, Walter Dodds, university distinguished professor of biology, helped demonstrate that nitrous oxide emissions from rivers and streams make up at least 10 percent of human-caused nitrous oxide emissions -- three times greater than current estimates ...

It's long been accepted by biologists that environmental factors cause the diversity—or number—of species to increase before eventually leveling off. Some recent work, however, has suggested that species diversity continues instead of entering into a state of equilibrium. But new research on lizards in the Caribbean not only supports the original theory that finite space, limited food supplies, and competition for resources all work together to achieve equilibrium; it builds on the theory by extending it over a much longer timespan.

The research was done by Daniel Rabosky ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – Less-invasive robotic surgery for upper airway and digestive track malignant tumors is as effective as other minimally invasive surgical techniques based on patient function and survival, according to University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas account for about 4 percent of malignant tumors diagnosed in the United States each year. Currently the standard minimally invasive surgery for these tumors is transoral laser microsurgery.

Previous studies have shown that the robotic surgery was better for patients ...

What goes in must come out, a truism that now may be applied to global river networks.

Human-caused nitrogen loading to river networks is a potentially important source of nitrous oxide emission to the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change and stratospheric ozone destruction.

It happens via a microbial process called denitrification, which converts nitrogen to nitrous oxide and an inert gas called dinitrogen.

When summed across the globe, scientists report this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy ...

Increasing acidity in the sea's waters may fundamentally change how nitrogen is cycled in them, say marine scientists who published their findings in this week's issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Nitrogen is one of the most important nutrients in the oceans. All organisms, from tiny microbes to blue whales, use nitrogen to make proteins and other important compounds.

Some microbes can also use different chemical forms of nitrogen as a source of energy.

One of these groups, the ammonia oxidizers, plays a pivotal role in determining ...

VIDEO:

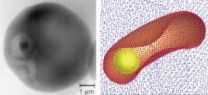

Malaria-infected red blood cells can be 50 times stiffer and have surface changes that disrupt the smooth flow of blood, depriving the brain and other organs of nutrients and oxygen....

Click here for more information.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Although the incidence of malaria has declined in all but a few countries worldwide, according to a World Health Organization report earlier this month, malaria remains a global threat. Nearly 800,000 people ...