(Press-News.org) Climate change is known to negatively affect agriculture and livestock, but there has been little scientific knowledge on which regions of the planet would be touched or what the biggest risks may be. New research led by Aalto University assesses just how global food production will be affected if greenhouse gas emissions are left uncut. The study is published in the prestigious journal One Earth on Friday 14 May.

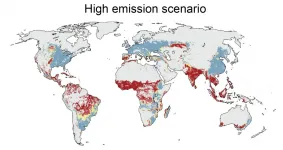

'Our research shows that rapid, out-of-control growth of greenhouse gas emissions may, by the end of the century, lead to more than a third of current global food production falling into conditions in which no food is produced today - that is, out of safe climatic space,' explains Matti Kummu, professor of global water and food issues at Aalto University.

According to the study, this scenario is likely to occur if carbon dioxide emissions continue growing at current rates. In the study, the researchers define the concept of safe climatic space as those areas where 95% of crop production currently takes place, thanks to a combination of three climate factors, rainfall, temperature and aridity.

'The good news is that only a fraction of food production would face as-of-yet unseen conditions if we collectively reduce emissions, so that warming would be limited to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius,' says Kummu.

Changes in rainfall and aridity as well as the warming climate are especially threatening to food production in South and Southeast Asia as well as the Sahel region of Africa. These are also areas that lack the capacity to adapt to changing conditions.

'Food production as we know it developed under a fairly stable climate, during a period of slow warming that followed the last ice age. The continuous growth of greenhouse gas emissions may create new conditions, and food crop and livestock production just won't have enough time to adapt,' says Doctoral Candidate Matias Heino, the other main author of the publication.

Two future scenarios for climate change were used in the study: one in which carbon dioxide emissions are cut radically, limiting global warming to 1.5-2 degrees Celsius, and another in which emissions continue growing unhalted.

The researchers assessed how climate change would affect 27 of the most important food crops and seven different livestock, accounting for societies' varying capacities to adapt to changes. The results show that threats affect countries and continents in different ways; in 52 of the 177 countries studied, the entire food production would remain in the safe climatic space in the future. These include Finland and most other European countries.

Already vulnerable countries such as Benin, Cambodia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana and Suriname will be hit hard if no changes are made; up to 95 percent of current food production would fall outside of safe climatic space. Alarmingly, these nations also have significantly less capacity to adapt to changes brought on by climate change when compared to rich Western countries. In all, 20% of the world's crop production and 18% of livestock production under threat are located in countries with low resilience to adapt to changes.

If carbon dioxide emissions are brought under control, the researchers estimate that the world's largest climatic zone of today - the boreal forest, which stretches across northern North America, Russia and Europe - would shrink from its current 18.0 to 14.8 million square kilometres by 2100. Should we not be able to cut emissions, only roughly 8 million square kilometres of the vast forest would remain. The change would be even more dramatic in North America: in 2000, the zone covered approximately 6.7 million square kilometres - by 2090 it may shrink to one-third.

Arctic tundra would be even worse off: it is estimated to disappear completely if climate change is not reined in. At the same time, the tropical dry forest and tropical desert zones are estimated to grow.

'If we let emissions grow, the increase in desert areas is especially troubling because in these conditions barely anything can grow without irrigation. By the end of this century, we could see more than 4 million square kilometres of new desert around the globe,' Kummu says.

While the study is the first to take a holistic look at the climatic conditions where food is grown today and how climate change will affect these areas in coming decades, its take-home message is by no means unique: the world needs urgent action.

'We need to mitigate climate change and, at the same time, boost the resilience of our food systems and societies - we cannot leave the vulnerable behind. Food production must be sustainable,' says Heino.

INFORMATION:

What The Study Did: Researchers analyzed changes in filled prescriptions for naloxone (medication to reverse opioid overdoses) during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and compared them with changes in opioid prescriptions and overall prescriptions.

Authors: Ashley L. O'Donoghue, Ph.D., of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0393)

Editor's Note: The ...

What The Study Did: Associations of staffing and testing interventions with COVID-19 transmission in nursing homes are examined in this decision analytical modeling study.

Authors: Rebecca Kahn, Ph.D., of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10071)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, ...

What The Study Did: This is a qualitative study that evaluates a crowdsourcing open call to gather community input for engaging the university community in COVID-19 safety strategies.

Authors: Suzanne Day, Ph.D., of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10090)

Editor's Note: This article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated the compliance of hospitals with a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ruling mandating that a list of charges for services, procedures and items be publicly available and in a machine-readable file.

Authors: David Hsiehchen, M.D., of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10109)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, ...

Tokyo, Japan - Oxygen is crucial to many forms of life. Its delivery to the organs and tissues of the body through the process of respiration is vital for most biological processes. Now, researchers at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) have shown that oxygen can be delivered through the wall of the intestine to compensate for the reduced availability of oxygen within the body that occurs in lung diseases that cause respiratory failure.

To breathe is to live; for higher animals, respiration involves absorbing oxygen and excreting carbon dioxide at gills or in the lungs. However, some animals have evolved alternative ventilatory mechanisms: loaches, catfish, sea cucumbers and orb-weaving spiders can absorb oxygen through their hindgut to ...

Scientists have uncovered the exact mechanism that causes new solar cells to break down, and suggest a potential solution.

Solar cells harness energy from the Sun and provide an alternative to non-renewable energy sources like fossil fuels. However, they face challenges from costly manufacturing processes and poor efficiency - the amount of sunlight converted to useable energy.

Perovskites are materials developed for next-generation solar cells. Although perovskites are more flexible cheaper to make than traditional silicon-based solar panels and deliver similar efficiency, perovskites ...

University of Alberta scientists have identified a receptor in cells that could be key to preventing permanent hearing loss in childhood cancer survivors who are being treated with the drug cisplatin. The researchers believe by inhibiting the receptor, they may be able to eliminate toxic side-effects from the drug that cause the hearing loss.

Cisplatin is an incredibly effective chemotherapeutic when it comes to treating solid tumours in children, contributing to an 80 per cent overall survival rate over five years, according to U of A researcher Amit Bhavsar, an assistant professor in the Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology. The problem ...

Boston - While overall emergency department visits have decreased during the pandemic, nonfatal opioid overdose visits have more than doubled. However, few patients who overdosed on opioids had received a prescription for naloxone, a medication designed to block the effects of opioids on the brain and rapidly reverse opioid overdose.

In a new study, clinician-researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) analyzed naloxone prescription trends during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and compared them to trends in opioid prescriptions and to overall prescriptions. The team's findings, published in the journal JAMA Health Forum, suggest patents with opioid misuse disorders may be experiencing a dangerous decrease in access to the overdose-reversing ...

A groundbreaking study led by engineering and medical researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how engineered immune cells used in new cancer therapies can overcome physical barriers to allow a patient's own immune system to fight tumors. The research could improve cancer therapies in the future for millions of people worldwide.

The research is published in Nature Communications, a peer-reviewed, open access, scientific journal published by Nature Research.

Instead of using chemicals or radiation, immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that helps the patient's immune system fight cancer. T cells are a type of white ...

KINGSTON, R.I. - May 14, 2021 - We are frequently reminded of how vulnerable our health and safety are to threats from nature or those who wish to harm us.

New sensors developed by Professor Otto Gregory, of the College of Engineering at the University of Rhode Island, and chemical engineering doctoral student Peter Ricci, are so powerful that they can detect threats at the molecular level, whether it's explosive materials, particles from a potentially deadly virus or illegal drugs entering the country.

"This is potentially life-saving technology," said Gregory. "We have detected ...