(Press-News.org) The last ice age ended almost 12 000 years ago in Norway. The land rebounded slowly as the weight of the ice disappeared and the land uplift caused many bays to become narrower and form lakes.

Fish became trapped in these lakes.

Sticklebacks managed to adapt when saltwater became freshwater, and they can still be found in today's coastal lakes along the Norwegian coast.

Saltwater gradually changed to brackish water and later to freshwater. This environmental change naturally led to a total replacement of the animal and plant life.

The exception is the tiny stickleback, which successfully adapted as saltwater became freshwater and can still be found in today's coastal lakes along the Norwegian coast. How in the world did this little fish manage to adapt to such big changes, even in several places at the same time?

The 12 000-year-old bones of three-spine stickleback can give us some answers.

The three-spine stickleback is found in freshwater lakes, in saltwater marine environments and in brackish water, a mixture of the two. Although the fish belong to the same species, they look a little different depending on where they are found.

Since so many lakes were cut off from the sea, we know that sticklebacks adapted to the environmental changes in multiple places simultaneously. Yet the changes happened independently of each other, without any interbreeding, which pointed to a genetic reason behind the phenomenon.

Three-spine sticklebacks are therefore well suited for the study of what biologists call "parallel evolution" - evolutionary changes that occur in parallel but independently of one another.

"Usually we only have access to present-day sticklebacks. We compare groups from freshwater and marine habitats and assume that fish from the sea today are genetically comparable to the marine fish that adapted to freshwater in earlier times," says Andrew Foote, an associate professor from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) University Museum and Bangor University in Wales.

Through some interdisciplinary collaboration, researchers gained access to 12 000-year-old bones from two sticklebacks in today's Hammerfest municipality.

These ancient artefacts can certainly provide a useful basis for study. But sticklebacks that live in marine environments today have also evolved since those times, so they might not be quite the same as the ones that adapted to freshwater at the end of the ice age. This makes studying them tricky for biologists.

"Although these bones belong to fish that died over ten thousand years ago, when most of Scandinavia was covered by ice, they contain fragments of DNA that we can study. The genes give us insight into the early stages of the transition from saltwater to freshwater," says Foote.

The results of the international cooperative effort were recently presented in the journal Current Biology. Experts in geology, ancient DNA and genetic evolution collaborated to compare present-day and ancient threespine sticklebacks.

Foote teamed up with professor and geneticist Tom Gilbert from the University of Copenhagen. They had access to a state-of-the-art laboratory for the study of ancient DNA and used newly developed methods to sequence the genomes of the 12 000-year-old sticklebacks.

"Research on threespine sticklebacks over the last 20 years has provided key insights into the genetic basis of parallel adaptation. We've found that adaptation can proceed via newly arising mutations, but often involves reusing an already existing genetic variation that spreads among populations," says Dr. Felicity Jones at the Max Planck Society's Friedrich Miescher Laboratory in Tübingen, Germany.

Populations are groups of animals of the same species that are geographically more or less separated from other groups of the same species.

"It's really striking that we could detect variants known to be adaptive to freshwater in one single marine colonizer by overcoming all the challenges related to sequencing ancient DNA. This conclusively demonstrates that freshwater-adaptive genetic variants were present in the stickleback populations that colonized freshwater lakes from the sea thousands of years ago," says doctoral student and lead author Melanie Kirch, who is also from the Friedrich Miescher laboratory.

This proves that gene variants that enable sticklebacks to live in freshwater already existed in stickleback populations in the ocean several thousand years ago. These marine fish could thus colonize the freshwater lakes that arose.

But Kirch also points out that the results show that parallel evolution has some limitations. "Even when the colonizing ancestor carried genetic variants known to be adaptive in freshwater, these variants aren't always present in the contemporary population. This tells us that even beneficial freshwater-adaptive variants can be lost during the evolutionary process of adaptation, likely by random chance - a process known as 'genetic drift,'" she says.

This ancient DNA has provided a window into the past and has enabled researchers to study the genetic makeup of the ancestors of today's fish. Researchers can thus track adaptations that have taken place over several thousand years that also help them understand more of the evolutionary process.

In this way, they can create better models and gain new insight into factors that affect the direction, speed and molecular basis behind evolution in nature.

The sticklebacks were found by Norwegian geologists who actually studied the land uplift that has taken place along the Norwegian coastline since the ice retreated from Scandinavia.

Geologists stumbled across the fish bones in several sediment samples taken from lakes along the coast. Sediments are materials that sink to the lake bottom over the years and are deposited in layers according to age, unless someone or something disturbs the order of the layers. In the more-or-less untouched lakes studied, the sediment layers show traces of the transition from a marine environment to a freshwater environment.

The fish bones washed out of the sediment samples were amazingly well preserved.

Carbon dating can help geologists reconstruct how sea levels have changed over time, but this time the technique was also useful in another way.

"The fish bones we washed out of the sediment samples were amazingly well preserved. We could immediately identify them as originating from threespine sticklebacks," says researcher Anders Romundset at the Norwegian Geological Survey.

They determined the age by carbon dating plant material that was found in the same layers as the bones. The analysis also showed that these particular fish had lived in brackish water, which indicates that the lake was close to becoming disconnected from the sea.

Since the bones were found in a transition period between marine and freshwater habitat, the genes showed both genetic variations associated with an adaptation to the sea, as well as some genes that clearly showed an adaptation to freshwater.

INFORMATION:

Source: Melanie Kirch, Anders Romundset, M. Thomas P. Gilbert, Felicity C. Jones, Andrew D. Foote. Ancient and modern stickleback genomes reveal the demographic constraints on adaptation. Current Biology. March 10, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.02.027

A reason for these findings could be due to the fact that Parkinson's patients often also have many risk factors for a severe course of Covid-19. For the first time, the cross-sectional study provides detailed nationwide data. The research team led by Professor Lars Tönges reports in the journal Movement Disorders of 4 May 2021.

Nationwide analysis of hospital data

The team headed by Lars Tönges has analysed data on Parkinson's treatment in 1,468 hospitals. The data were taken from nationwide databases in which information on the treated diseases and of treatments carried out in hospitals is publicly collected, for example by the Institute for the Hospital Remuneration System or the Federal Statistical Office.

A comparison between the period of the first ...

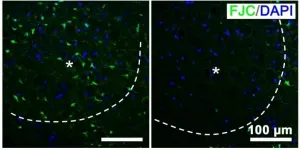

Blocked blood vessels in the brains of stroke patients prevent oxygen-rich blood from getting to cells, causing severe damage. Plants and some microbes produce oxygen through photosynthesis. What if there was a way to make photosynthesis happen in the brains of patients? Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Nano Letters have done just that in cells and in mice, using blue-green algae and special nanoparticles, in a proof-of-concept demonstration.

Strokes result in the deaths of 5 million people worldwide every year, according to the World Health Organization. Millions more survive, but they often experience disabilities, such as difficulties with speech, swallowing or memory. The most common cause is a blood vessel blockage in the brain, and the best way to ...

WASHINGTON, DC (May 19, 2021) - Human genetics and genomics contributed $265 billion to the U.S. economy in 2019 and has the potential to drive significant further growth given major new areas of application, according to a new report issued today by the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG). The findings indicate that this research and industry sector has seen its annual impact on the U.S. economy grow five-fold in the last decade and outlined at least eight areas of expanding impact for human health and society. ASHG commissioned and funded the report and is grateful for generous additional contributions from Invitae and Regeneron. ...

An international research team led by Professor Charles Gauthier from the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) has discovered a new molecule with potential to revolutionize the biosurfactant market. The team's findings have been published in Chemical Science, the Royal Society of Chemistry's flagship journal.

Surfactants are synthesized from petroleum and are the main active ingredient in most soaps, detergents, and shampoos. Biosurfactants, produced by bacteria, are safer and can replace synthetic surfactants.

Rhamnolipid molecules are some ...

Pregnant women made only modest dietary changes after being diagnosed with gestational diabetes, according to a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health. Women with gestational diabetes are generally advised to reduce their carbohydrate intake, and the women in the study did cut their daily intake of juice and added sugars. They also increased their intake of cheese and artificially sweetened beverages. However, certain groups of women did not reduce their carbohydrate intake, including women with obesity, had more than one child, were Hispanic, had a high school degree or less, or were between the ages of 35-41 years.

The study was led by Stefanie N. Hinkle, Ph.D., of the Epidemiology Branch at NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver ...

WASHINGTON (May 19, 2021)--Early online support for the Boogaloos, one of the groups implicated in the January 2021 attack on the United States Capitol, followed the same mathematical pattern as ISIS, despite the stark ideological, geographical and cultural differences between their forms of extremism. That's the conclusion of a new study published today by researchers at the George Washington University.

"This study helps provide a better understanding of the emergence of extremist movements in the U.S. and worldwide," Neil Johnson, a professor of physics at GW, said. "By identifying hidden common patterns in what seem to be completely unrelated movements, topped with a rigorous mathematical description of how they develop, our ...

DALLAS, May 19, 2021 -- Steps to ensure safety and mitigate the spread of COVID-19 have had some unintended consequences on the management of chronic conditions such as high blood pressure, a leading cause of heart disease and health disparities in the United States. COVID-19 has disproportionately affected people from different racial and ethnic groups, those who are from under-resourced populations and communities that face historic or systemic disadvantages. Discussions and research are ongoing to address what many experts label as long-existing inequities in the U.S. health system, according to information published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open access journal of the American Heart Association.

"Media coverage has examined how ...

Chronic exposure to second-hand smoke results in lower body weight and cognitive impairments that more profoundly affects males, according to new research in mice led by Oregon Health & Science University.

The study published today in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives.

"The hope is that we can better understand these effects for policymakers and the next generation of smokers," said lead author Jacob Raber, Ph.D., professor of behavioral neuroscience in the OHSU School of Medicine. "Many people still smoke, and these findings suggest that that the long-term health effects can be quite serious for people who are chronically exposed to second-hand smoke."

The research examined daily exposure of 62 mice over a period of 10 months. Researchers used a specially designed ...

A new article from Liverpool ocular researchers demonstrates that small uveal (intraocular) melanomas are not always harmless, as the current paradigm suggests.

Instead, a reasonable proportion of them have molecular genetic alterations, which categorises them as highly metastatic tumours. The article recommends that they should not be observed but rather treated immediately, to improve patients' chances of survival.

The paper shows that uveal melanoma patients with small tumours, when treated within a certain time frame in Liverpool, do indeed have improved outcomes.

The study was undertaken by researchers ...

Invasions by alien insect and animal species have much in common with outbreaks of infectious diseases and could tell us a great deal about how pandemics spread, according to a research paper published today.

Biological invasions, where animals, insects, plants and microorganisms are transported around the globe by humans, are becoming more common and have a global annual cost of at least £118billion.

An investigation by an international team of scientists, including the University of Leeds' School of Biology, says the emergence of human diseases share many of the same challenges as species invasions and that studying them together could provide solutions.

Co-author of the report, Dr Alison M. Dunn, a Professor of Ecology in the School of Biology, ...