(Press-News.org) Traditionally, an infection is thought to happen when microbes - bacteria, fungi, or viruses - enter and multiply in the body, and its severity is associated with how prevalent the microbes are in the body.

Now, an international research team led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) has proposed a new way of understanding infections. Their study of close to 400 respiratory samples from patients with bronchiectasis, a chronic lung condition, has shown that microbes in the body exist as a network, and that an infection's severity could be a result of interactions between these microbes.

Through statistical modelling of data from these respiratory samples, the scientists found that flare-ups of coughs and breathlessness (known as exacerbations) occurred more often when there were 'negative interactions' between communities of bacteria, viruses and fungi in the airways. A negative interaction occurs when the microbes compete rather than cooperate with one another.

These findings, published in one of the world's leading scientific journals Nature Medicine in April, bring the scientists one step closer to developing a new way of tackling infections, by targeting microbial interactions rather than the specific microbes.

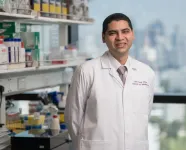

Assistant Professor Sanjay Haresh Chotirmall from the NTU Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, who led the study, said: "Our current understanding of infections is that they occur when harmful microbes enter our bodies. This model of understanding, however, fails to account for resident microbes or explain why some patients with infection respond to antibiotics to which the microbe is resistant in laboratory testing. We are therefore proposing that microbes exist as networks, where interactions happen and that the resistant antibiotic in this case targets another microbe with which the culprit is interacting. We therefore can potentially improve clinical outcomes by breaking such crosstalk.

"The findings of our study are the first steps in providing a more holistic view of how infections occur. While our study looked at patients with bronchiectasis, we believe this concept applies to all forms of infection - whether skin, lung, or a gastrointestinal infection. This way of looking at infections potentially changes our understanding of infection and may offer fresh ways of treating them."

Associate Professor John Abisheganaden, co-author of the study and Head of Department of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, said: "By applying an integrated and holistic method, this study provides a new and fresh approach to our understanding of respiratory infection. Applying this precision-medicine approach can help the managing physician better understand and choose the most appropriate antibiotic or other therapy to confer clinical benefit - in short, to guide us to the right treatment at the right time, and for the best outcome."

Microbial interactions and infection

For their study, the scientists looked at patients with bronchiectasis, a disease of high Asian prevalence, where airways dilate irreversibly and, where infection promotes progression. Targeting bacteria with antibiotics reduces bacterial load and accompanying inflammation, which in turn alleviates symptoms and improves clinical outcomes.

To investigate interactions between microbes in the airways of patients with bronchiectasis, the team collected respiratory (sputum) samples from 383 patients from Singapore, Malaysia, Italy, and Scotland, including samples before, during and after bronchiectasis flare-ups.

After analysing the genetic material from bacteria, fungi and viruses in the samples, the scientists assessed for possible microbial interactions and found that patients with frequent flare-ups had more negative interactions, where microbes compete rather than cooperate, and that the number of such negative interactions increased even further during a flare-up. While changes to interactions between microbes during flare-ups was detected, there was surprisingly minimal change to the type and quantity of microbes present during a flare-up, and even after antibiotics were administered.

New treatment possibilities

The scientists believe that these findings suggest that microbial interactions potentially drive frequent flare-ups in patients.

Using these findings, the scientists have developed an online tool

to help other researchers and physicians analyse microbial interactions in their own patient samples through the microbes' genetic sequences.

Asst Prof Chotirmall, who is also NTU Provost's Chair in Molecular Medicine, said: "We are proposing a fresh way to view infection, as networks rather than individual microbes. Targeting microbial interactions within an established network may promote more judicious antibiotic use and help curb rising antimicrobial resistance."

The team is currently exploring the use of probiotics to treat bronchiectasis by regulating microbiomes within the air passages.

INFORMATION:

The interdisciplinary team includes researchers from Singapore's NTU LKCMedicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Changi General Hospital, and Singapore General Hospital; the University of Malaya in Malaysia, Italy's Fondazione IRCCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico and the University of Milan; the University of Sydney in Australia; the University of Dundee in Scotland; and the University of Exeter in the UK.

Note to Editors:

Paper titled "Integrative microbiomics in bronchiectasis exacerbations" published in Nature Medicine, 5 April 2021.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01289-7

Media contact:

Foo Jie Ying

Manager, Corporate Communications Office

Nanyang Technological University

Email: jieying@ntu.edu.sg

About Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

A research-intensive public university, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) has 33,000 undergraduate and postgraduate students in the Engineering, Business, Science, Humanities, Arts, & Social Sciences, and Graduate colleges. It also has a medical school, the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, established jointly with Imperial College London.

NTU is also home to world-class autonomous institutes - the National Institute of Education, S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Earth Observatory of Singapore, and Singapore Centre for Environmental Life Sciences Engineering - and various leading research centres such as the Nanyang Environment & Water Research Institute (NEWRI) and Energy Research Institute @ NTU (ERI@N).

Ranked amongst the world's top universities by QS, NTU has also been named the world's top young university for the past seven years. The University's main campus is frequently listed among the Top 15 most beautiful university campuses in the world and has 57 Green Mark-certified (equivalent to LEED-certified) buildings, of which 95% are certified Green Mark Platinum. Apart from its main campus, NTU also has a campus in Novena, Singapore's healthcare district.

Under the NTU Smart Campus vision, the University harnesses the power of digital technology and tech-enabled solutions to support better learning and living experiences, the discovery of new knowledge, and the sustainability of resources.

For more information, visit http://www.ntu.edu.sg.

Among the large cast of microbiome players, bacteria have long been hogging the spotlight. But the single-celled organisms known as protists are finally getting the starring role they deserve.

A group of scientists who study the interactions between plants and microbes have released a new study detailing the dynamic relationships between soil-dwelling protists and developing plants, demonstrating that soil protists respond to plant signals much like bacteria do.

An enormous variety and diversity of microbes live in soil, and studying how these organisms interact with each ...

For young plants, timing is just about everything. Now, scientists have found that herbivores, animals that consume plants, have a lot to say about evolution at this vulnerable life stage.

Once a plant seedling breaches the soil surface and begins to grow, a broad range of factors will determine whether it thrives or perishes.

Scientists have long perceived that natural selection favors early rising seeds. Seedlings that emerge early in the growing season should have a competitive advantage in monopolizing precious soil resources. Early growth also should mean more access to light, since early growers can block sunlight for seedlings that emerge later in the season.

Despite plenty of proof that germinating early is highly advantageous, many plants germinate ...

LA JOLLA, CALIF. - May 19, 2021 - A study led by scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute has identified a tumor marker that may be used to predict which breast cancer patients will experience resistance to endocrine therapy. The research offers a new approach to selecting patients for therapy that targets HER2, a protein that promotes the growth of cancer cells, to help avoid disease relapse or progression of endocrine-sensitive disease.

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Nearly 80% of breast tumors are estrogen receptor (ER)-positive. For decades, ...

Turns out the old adage, "monkey see, monkey do," does ring true -- even when it comes to cannabis use. However, when cannabis use involves youth it's see, think, then do, says a team of UBC Okanagan researchers.

The team found that kids who grow up in homes where parents consume cannabis will more than likely use it themselves. Parental influence on the use of cannabis is important to study as it can help with the development of effective prevention programs, explains Maya Pilin, a doctoral psychology student in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

"Adolescence is a critical period in which drug and alcohol experimentation takes place and when cannabis use is often initiated," says Pilin. "Parents are perhaps the most influential socializing agent for ...

People with bipolar disorder may not take their medication because of side effects, fear of addiction and a preference for alternative treatment - according to research from Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT) and the University of East Anglia (UEA).

Nearly half of people with bipolar disorder do not take their medication as prescribed leading to relapse, hospitalisation, and increased risk of suicide.

A new study, published today, reveals six key factors that stop people taking their medication as prescribed.

These include whether they are experiencing side effects, difficulties in remembering to take medication and a lack of support from family, friends and healthcare ...

Researchers at the University of Eastern Finland have found a potential neuroprotective effect of a protein modification that could be a therapeutic target in early Alzheimer's disease. The new study investigated the role of MECP2, a regulator of gene expression, in Alzheimer's disease related processes in brain cells. The study found that phosphorylation of MECP2 protein at a specific amino acid decreases in the brain as Alzheimer's disease is progressing. Abolishing this phosphorylation of MECP2 in cultured mouse neurons upon inflammatory stimulation enhanced their viability and ...

A study led by MedUni Vienna (Institute of Cancer Research and Comprehensive Cancer Center Vienna) sheds light on the mechanisms that lead to extremely aggressive metastasis in a particular type of pancreatic cancer, the basal subtype of ductal adenocarcinoma. The results contribute to a better understanding of the disease. The study has recently been published in the leading journal "Gut".

The most prevalent form of pancreatic cancer, Pancreatic Ductal AdenoCarcinoma (PDAC) is usually divided into two subtypes, a classical subtype and a basal subtype. The latter is highly aggressive and tends towards early metastasis. One of the distinguishing features between the two subtypes is that the classical subtype exhibits the protein GATA6. This is no longer present ...

Water in the high-mountain regions has many faces. Frozen in the ground, it is like a cement foundation that keeps slopes stable. Glacial ice and snow supply the rivers and thus the foothills with water for drinking and agriculture during the melt season. Intense downpours with flash floods and landslides, on the other hand, pose a life-threatening risk to people in the valleys. The subsoil with its ability to store water therefore plays an existential role in mountainous regions.

But how can we determine how empty or full the soil reservoir is in areas that are difficult to access? Researchers at the German Research Centre for Geosciences (GFZ), together with colleagues from Nepal, have now demonstrated an elegant method to track groundwater dynamics in high ...

The latest findings show that with clever science, a single fingerprint left at a crime scene could be used to determine whether someone has touched or ingested class A drugs.

In a paper published in Royal Society of Chemistry's Analyst journal, a team of researchers at the University of Surrey, in collaboration with the National Centre of Excellence in Mass Spectrometry Imaging at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) and Ionoptika Ltd reveal how they have been able to identify the differences between the fingerprints of people who touched cocaine compared with those who have ingested the drug - even if the hands are not washed. The smart science behind the advance is the mass spectrometry imaging tools applied to the detection of cocaine ...

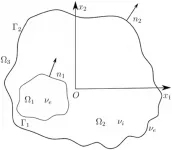

Problems for eigenmodes of a two-layered dielectric microcavity have become widespread thanks to the research of A.I. Nosich, E.I. Smotrova, S.V. Boriskina and others since the beginning of the 21st century. The KFU team first tackled this topic in 2014; undergraduates started working under the guidance of Evgeny Karchevsky, Professor of the Department of Applied Mathematics of the Institute of Computational Mathematics and Information Technology.

In this paper, the researchers discuss a model of a 2D active microcavity with a piercing hole and the possibility of a compromise between high directionality of radiation ...