(Press-News.org) New research by scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences reveals that the immune system has an effective backup plan to protect the body from infection when the "master regulator" of the body's innate immune system fails. The study appears in the December 19 online issue of the journal Nature Immunology.

The innate immune system defends the body against infections caused by bacteria and viruses, but also causes inflammation which, when uncontrolled, can contribute to chronic illnesses such as heart disease, arthritis, type 2 diabetes and cancer. A molecule known as nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) has been regarded as the "master regulator" of the body's innate immune response, receiving signals of injury or infection and activating genes for microbial killing and inflammation.

Led by Michael Karin, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Pharmacology, the UC San Diego team studied the immune function of laboratory mice in which genetic tools were used to block the pathway for NF-κB activation. While prevailing logic suggested these mice should be highly susceptible to bacterial infection, the researchers made the unexpected and counterintuitive discovery that NF-κB-deficient mice were able to clear bacteria that cause a skin infection even more quickly than normal mice.

"We discovered that loss of NF-κB caused mice to produce a potent immune-activating molecule known as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), which in turn stimulated their bone marrow to produce dramatically increased numbers of white blood cells known as neutrophils," said Karin. Neutrophils are the body's front-line defenders against infection, capable of swallowing and killing bacteria with a variety of natural antibiotic enzymes and proteases.

The new research demonstrates that the innate immune system deploys two effective strategies to deal with invasive bacterial infection, and that the IL-1β system provides an important safety net when NF-κB falls short.

"Having a backup system in place is critical given the diverse strategies that bacterial pathogens have evolved to avoid bacterial clearance," said Victor Nizet, MD, professor of pediatrics and pharmacy, whose laboratory conducted the infectious challenge experiments in the study. "A number of bacteria are known to suppress pathways required for NF-κB activation, so IL-1β signaling could help us recognize and respond to these threats."

While helpful in short-term defense against a severe bacterial infection, the dramatic increase in neutrophil counts seen in the NF-κB-deficient mice ultimately came at a cost. Over many weeks, these activated immune cells produced inflammation in multiple organs and led to the premature death of the animals. Long-term blockade of NF-κB signaling has been explored extensively by the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry as a strategy for anti-inflammatory or anti-cancer therapy, perhaps unaware of the risks suggested by this new research.

"One might contemplate adding a second inhibitor of IL-1β signaling to protect against the over-exuberant neutrophil response," said Karin. "Unfortunately, loss of both the NF-κB pathway and the backup IL-1β pathway rendered the mice highly susceptible to invasive bacterial infection which they no longer cleared."

Altogether, the UC San Diego research sheds new light on the complex and elegant regulatory pathways required for a highly effective innate immune system. The scientists noted that future investigations must take into account these interrelationships in order to design novel drugs against inflammatory diseases that achieve their treatment goals while minimizing the risk of infection.

INFORMATION:

Lead authors of the study were former UC San Diego postdoctoral fellows Li-Chung Hsu, now at National Taiwan University in Taipei, and Thomas Enzler, currently at the University of Goettingen in Germany. Additional contributors include Guan-Yi Yu and Vladislav Temkin of the UCSD Department of Pharmacology; Anjuli Timmer of the UCSD Department of Pediatrics; Jun Seita and Irving Weissman of the Institute for Stem Cell Biology at Stanford University School of Medicine; Chih-Yuan Lee, Ting-Yu Lai, Guann-Yi Yu, and Liang-Chuan Lai of National Taiwan University; and Ursula Sinzig and Thiha Aung of the University of Goettingen.

The research of Karin, Nizet and Weissman was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Researchers discover human immune system has emergency backup plan

2010-12-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists take plasmon lasers out of deep freeze

2010-12-21

Berkeley – Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, have developed a new technique that allows plasmon lasers to operate at room temperature, overcoming a major barrier to practical utilization of the technology.

The achievement, described Dec. 19 in an advanced online publication of the journal Nature Materials, is a "major step towards applications" for plasmon lasers, said the research team's principal investigator, Xiang Zhang, UC Berkeley professor of mechanical engineering and faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

"Plasmon ...

Despite damage, membrane protein structure can be seen using new X-ray technology, study reveals

2010-12-21

Australian researchers have identified a way to measure the structure of membrane proteins despite being damaged when using X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs), a discovery that will help fast track the development of targeted drugs using emerging XFELs technology.

About 70% of drugs on the market today depend on the activity of membrane proteins, which are complex molecules that form the membranes of the cells in our body.

A major problem for the design of new pharmaceuticals, often known as the "membrane protein problem", is that they do not form the crystals needed ...

Study identifies cells that give rise to brown fat

2010-12-21

BOSTON – December 20, 2010 – In some adults, the white fat cells that we all stockpile so readily are supplemented by a very different form of fat—brown fat cells, which can offer the neat trick of burning energy rather than storing it. Researchers at Joslin Diabetes Center, which last year led the way in demonstrating an active role for brown fat in adults, now have identified progenitor cells in mouse white fat tissue and skeletal muscle that can be transformed into brown fat cells.

"This finding opens up a whole new avenue for researchers interested in designing molecules ...

Acid suppressive medication may increase risk of pneumonia

2010-12-21

Using acid suppressive medications, such as proton pump inhibitors and histamine2 receptor antagonists, may increase the risk of developing pneumonia, states an article in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) (pre-embargo link only) http://www.cmaj.ca/embargo/cmaj092129.pdf.

Acid suppressive drugs are the second leading medication worldwide, totaling over US$26 billion in sales in 2005. Recently, medical literature has looked at unrecognized side effects in popular medications and their impact on public health.

This systematic review, which incorporated all relevant ...

Strict heart rate control provides no advantage over lenient approach

2010-12-21

Strictly controlling the heart rate of patients with atrial fibrillation provides no advantage over more lenient heart rate control, experts report in a focused update of the 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation.

The new recommendations, published in Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association, the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, and HeartRhythm Journal, are updates of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients ...

Young female chimps treat sticks like dolls

2010-12-21

Researchers have reported some of the first evidence that chimpanzee youngsters in the wild may tend to play differently depending on their sex, just as human children around the world do. Although both young male and female chimpanzees play with sticks, females do so more often, and they occasionally treat them like mother chimpanzees caring for their infants, according to a study in the December 21st issue of Current Biology, a Cell Press publication.

The findings suggest that the consistently greater tendency, across all cultures, for girls to play more with dolls ...

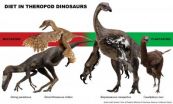

Meat-eating dinosaurs not so carnivorous after all

2010-12-21

December 20th, 2010 – Tyrannosaurus rex may have been a flesh-eating terror but many of his closest relatives were more content with vegetarian fare, a new analysis by Field Museum scientists has found.

The scientists, Lindsay Zanno and Peter Makovicky, who will publish their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used statistical analyses to determine the diet of 90 species of theropod dinosaurs. Their results challenge the conventional view that nearly all theropods hunted prey, especially those closest to the ancestors of birds. ...

Brain imaging predicts future reading progress in children with dyslexia

2010-12-21

NASHVILLE, Tenn.—Brain scans of adolescents with dyslexia can be used to predict the future improvement of their reading skills with an accuracy rate of up to 90 percent, new research indicates. Advanced analyses of the brain activity images are significantly more accurate in driving predictions than standardized reading tests or any other measures of children's behavior.

The finding raises the possibility that a test one day could be developed to predict which individuals with dyslexia would most likely benefit from specific treatments.

The research was published ...

Expansion of HIV screening cost-effective in reducing spread of AIDS, Stanford study shows

2010-12-21

STANFORD, Calif. — An expanded U.S. program of HIV screening and treatment could prevent as many as 212,000 new infections over the next 20 years and prove to be very cost-effective, according to a new study by Stanford University School of Medicine researchers.

The researchers found that screening high-risk people annually and low-risk people once in their lifetimes was a worthwhile and cost-effective approach to help curtail the epidemic. The screening would have to be coupled with treatment of HIV-infected individuals, as well as programs to help change risky behaviors.

"We ...

Neuroimaging at Stanford helps to predict which dyslexics will learn to read

2010-12-21

STANFORD, Calif. — Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have used sophisticated brain imaging to predict with 90 percent accuracy which teenagers with dyslexia would improve their reading skills over time.

Their work, the first to identify specific brain mechanisms involved in a person's ability to overcome reading difficulties, could lead to new interventions to help dyslexics better learn to read.

"This gives us hope that we can identify which children might get better over time," said Fumiko Hoeft, MD, PhD, an imaging expert and instructor at ...