The findings were reported by Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center researchers in two published studies.

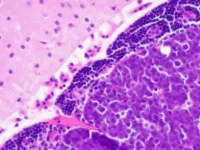

Medulloblastoma is the most common malignant pediatric brain tumor. A subset of patients with tumors known as Group 3 MYC-amplified medulloblastoma have an overall survival rate of less than 25%. In these patients, the cancer-promoting MYC oncogene drives cancer cell growth by altering cancer cell metabolism. Cancer cells use energy in ways that are different from normal cells, so they are potentially vulnerable to therapies that target the abnormal metabolic pathways downstream of MYC.

In the first study, published March 22 in the Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, pediatric oncologist and senior author Eric Raabe, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, focused on the metabolism altering drug DON (6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine). DON is a naturally occurring compound studied in adult and pediatric cancer clinical trials since the 1980s, but it was never systematically tested against MYC-driven brain tumors.

Although DON was safe in children in early cancer clinical trials, it is not currently clinically available.

The research team, led by Barbara Slusher, Ph.D., M.A.S., director of Johns Hopkins Drug Discovery and professor of neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, modified DON to increase its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, creating a DON prodrug, JHU395. In a prodrug, the chemistry is changed so that the drug is activated only in cancer cells.

"The promise of DON prodrugs is to develop a treatment that wouldn't hurt normal cells but could be released preferentially in brain cancer cells," says Raabe.

In one set of experiments, investigators treated human high-MYC medulloblastoma cell lines with JHU395 and with DON. They found the prodrug effectively suppressed growth and killed the cancer cells at lower concentrations compared to DON alone.

Next, mice bearing implanted human medulloblastoma tumors were treated with JHU395. The researchers found the treatment led to selective killing of the MYC-driven cancer cells, while normal brain cells were spared. Furthermore, JHU395 treatment significantly extended survival. Treated mice lived nearly twice as long as mice given placebo.

"JHU395 is equally effective as DON at a lower dose because it has better penetration of the brain cancer cells," Raabe says. "Coming up with a new therapy with potentially reduced side effects means we can combine drugs for better patient survival, which is what this is all about."

In a second study, published online Feb. 8 in Cancer Letters, Raabe and colleagues at three other cancer research institutions targeted the mammalian rapamycin complexes involved in cell metabolism. The protein mTOR signals cancer cells to grow, invade healthy tissue and resist therapy.

Previous research showed that, in addition to high MYC expression, aggressive pediatric medulloblastoma tumors have high-level mTOR expression, pointing investigators toward mTOR inhibitors as having possible therapeutic value. A bioinformatics drug screen identified TAK228 (also known as sapanisertib), a brain-penetrating mTORC1/2 kinase inhibitor as a potentially effective agent for children, Raabe says.

Researchers found that TAK228 inhibited mTORC1/2, suppressed tumor cell growth up to 75% and effectively killed MYC-driven human medulloblastoma cancer cells.

Next, investigators focused on measuring the abnormal metabolism of MYC-driven medulloblastoma. In cancer, elevated glutathione is one means by which tumor cells become resistant to chemotherapy. Glutathione specifically allows cells to block the effect of chemotherapy drugs containing platinum, such as cisplatin and carboplatin. These platinum-containing drugs are some of the major components of medulloblastoma therapy. In human medulloblastoma tumors grown in mice, Raabe and colleagues found that the tumor cells have more glutathione than normal brain cells. Using the excess glutathione may be one way these cancer cells resist chemotherapy.

The researchers found that the TAK228 mTOR inhibitor disrupted and decreased glutathione synthesis in cancer cells. When they treated mice that had high-MYC medulloblastoma brain tumors with a combination of TAK228 and carboplatin, the combination effectively killed tumor cells and extended survival more than either drug used alone. Mice treated with combination therapy lived nearly twice as long as control mice. Of the combination-treated mice, 20% were considered very long survivors, living nearly 80 days after the start of the experiment, while all control mice died from their tumor within 25 days.

"By targeting the mTOR pathway, TAK228 overcame a key resistance mechanism that cancer cells have to traditional chemotherapy," Raabe says. "These MYC-driven cancers make a lot of glutathione -- they're growing so fast they need a lot of it. TAK228 reduces the amount they can make, and that makes them vulnerable to the chemotherapy."

"This is valuable pre-clinical data for future trials in children of combination mTOR inhibitor with traditional chemotherapy, which could ultimately change outcomes for children who will be diagnosed with MYC-driven medulloblastoma," he adds.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology study are Khoa Pham, Micah Maxwell, Heather Sweeney, Jesse Alt, Rana Rais, Charles Eberhart and Barbara Slusher.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R01NS103927) and National Cancer Institute (R01 R01CA229451), the Spencer Grace Foundation, the Ace for the Cure Foundation, the Giant Food Pediatric Cancer Research Fund and a National Cancer Institute core grant to the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Other researchers participating in the Cancer Letters study are Rachael Maynard, Brad Poore, Allison Hanaford, Khoa Pham, Madison James, Jesse Alt, Youngran Park, Barbara Slusher and Charles Eberhart from Johns Hopkins, Pablo Tamayo and Jill Mesirov from the University of California San Diego, and Tenley Archer and Scott Pomeroy from the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University and the Harvard Medical School.

Funding was provided by Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer, the Spencer Grace Foundation, the Ace for the Cure Foundation, the Giant Food Pediatric Cancer Research Fund, the National Institutes of Health (U24CA220341, U01CA217885, U24CA194107, U54CA209891 and U01 CA184898) and a National Cancer Institute support grant to the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins.

Under a license agreement between Dracen Pharmaceuticals and The Johns Hopkins University, Slusher, Rais and Alt are entitled to royalty distributions related to technology used in the research described in Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. Also, Slusher and Rais are founders of and hold equity in Dracen Pharmaceuticals. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by The Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.