(Press-News.org) Ancient pollen samples and a new statistical approach may shed light on the global rate of change of vegetation and eventually on how much climate change and humans have played a part in altering landscapes, according to an international team of researchers.

"We know that climate and people interact with natural ecosystems and change them," said Sarah Ivory, assistant professor of geosciences and associate in the Earth and Environmental Systems Institute, Penn State. "Typically, we go to some particular location and study this by teasing apart these influences. In particular, we know that the impact people have goes back much earlier than what is typically accepted as the case. However, we haven't been able to observe the patterns created by these processes globally or long-term."

Over the past 100 years, researchers have collected datasets of fossil pollen samples from coring existing and dried-up lakes. In the current study, rather than looking at collections from individual sites, the researchers looked at the world-wide compilation of pollen data. They examined 1,181 fossil pollen sequences using a statistical approach that is an extension of standard practices, but that uses a 500-year rolling window to determine how much and how quickly vegetation changed through time in locations around the world.

One early, major change in vegetation is seen when the most recent glaciers began to melt. Pollen changes during this period show significant vegetation change. Although there were humans around at the time, they mostly lived in what are now the tropics or were widely dispersed. The magnitude of vegetation change seen suggests that at this point, climate changes were responsible.

Another major signal of vegetation change appears with the expansion of agriculture, which is usually considered to have occurred 3,000 to 4,000 years ago.

The researchers report today (May 21) in Science, "We detect a worldwide acceleration in the rates of vegetation compositional change beginning between 4.6 and 2.9 thousand years ago that is globally unprecedented over the past 18,000 years in both magnitude and extent."

They add that "the scale of human effects on terrestrial ecosystems exceeds even the climate-driven transformation of the last deglaciation."

Ivory noted that humans were influencing vegetation long before agriculture became a major factor.

While researchers have known of humanity's influence on the environment, and on vegetation in particular, previous studies have been on a local or regional scale. As early as 700,000 years ago hominids used fire and 8,000 years ago extensive agricultural land use show human influence on vegetation changes far into the past.

"People have a presence, they are everywhere," said Ivory. "Even in places that are not very urbanized or might appear to be quite wild, often in the archaeological and fossil pollen record, we see legacies of the impact of people very early. How do biodiversity and resources change through time with respect to climate change and the impact that people have already had? How is it likely to change in the future?" she added.

While modern observations can supply some information, understanding what happened more than 100 years ago is only possible by looking at the fossil record and only on a global scale. That knowledge can inform on what might happen in the future.

"There were a lot of dynamic things happening over the last 11,000 years," said Ivory. "Ecosystems were reorganizing. Many of the megafauna went away. It's hard to explain all that without climate. However, during the later part of this period, there aren't major climate changes, so it is more likely human technology that is responsible."

According to Ivory, one next step is to incorporate a better understanding of what is causing these changes into the study. She also would like to look more closely at Africa.

"Human impacts in Africa are much more complex than in Europe or North America," said Ivory. "There is a much longer period when humans were around, developing culture, developing new technologies. We also don't have nearly as much data."

Pollen sample coverage of Africa is uneven. In the Sahara, samples only date to 6,000 years ago when lakes dried up and the area became a desert. Other areas, like East Africa, are well-covered. Ivory wants to consolidate the African data from a now-defunct database and look specifically at how changes in climate as well as changes in small-scale agriculture and hunter-gatherer and pastoralist practices interact with the landscape.

"One thing that the study does is make a distinction between detection and attribution," Ivory said. "We have the ability to test and detect times when ecosystems are changing. We can qualitatively say climate or people are responsible for the changes, but the attribution of who or what in each instance is the cause is still missing."

INFORMATION:

Other researchers on the project include first authors Ond?ej Motti, postdoctoral fellow in biological sciences, and Suzette G. A. Flantua, postdoctoral fellow HOPE project, University of Bergen, Norway. Also at the University of Bergen are Kuber P. Bhatta, postdoctoral fellow in biological sciences; Vivian A. Felde, researcher on the HOPE project; and Alastair W. R. Seddon, associate professor of biological sciences.

Thomas Giesecke, associate professor of physical geography, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands; Simon Goring, assistant research scientist, and John W. Williams, professor, both in the department of geography and the Center for Climatic Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Eric C. Grimm (deceased), University of Minnesota; Simon Heberle, professor of archaeology, Australian National University, Canberra; Henry Hoogheimstra, emeritus professor, Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystems Dynamics, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Petr Kuneš, Department of Botany, Catholic University, Prague, Czech Republic; and Steffen Wolters, senior researcher, Lower Saxony Institute for Historical Coastal Research, Wilhelmshaven, Germany were all part of the project.

The European Research Council, Belmont Forum and the U.S. National Science Foundation supported this research.

A compound used widely in candles offers promise for a much more modern energy challenge--storing massive amounts of energy to be fed into the electric grid as the need arises.

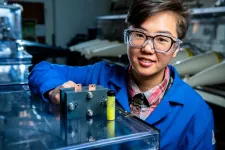

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory have shown that low-cost organic compounds hold promise for storing grid energy. Common fluorenone, a bright yellow powder, was at first a reluctant participant, but with enough chemical persuasion has proven to be a potent partner for energy storage in flow battery systems, large systems that store energy for the grid.

Development of such storage is critical. When the grid goes offline due to severe weather, for instance, the large batteries under ...

Wherever ecologists look, from tropical forests to tundra, ecosystems are being transformed by human land use and climate change. A hallmark of human impacts is that the rates of change in ecosystems are accelerating worldwide.

Surprisingly, a new study, published today in Science, found that these rates of ecological change began to speed up many thousands of years ago. "What we see today is just the tip of the iceberg" noted co-lead author Ondrej Mottl from the University of Bergen (UiB). "The accelerations we see during the industrial revolution and modern periods have a deep-rooted history stretching back in time."

Using a global network of over 1,000 fossil pollen records, the team found - and expected to find - a first peak ...

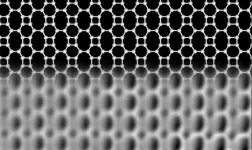

Carbon exists in various forms. In addition to diamond and graphite, there are recently discovered forms with astonishing properties. For example graphene, with a thickness of just one atomic layer, is the thinnest known material, and its unusual properties make it an extremely exciting candidate for applications like future electronics and high-tech engineering. In graphene, each carbon atom is linked to three neighbours, forming hexagons arranged in a honeycomb network. Theoretical studies have shown that carbon atoms can also arrange in other flat network patterns, while still binding to three neighbours, but none of these predicted networks had been realized until now.

Researchers at the University of Marburg ...

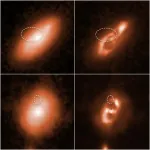

Analyzing data obtained with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), researchers found a galaxy with a spiral morphology by only 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang. This is the most ancient galaxy of its kind ever observed. The discovery of a galaxy with a spiral structure at such an early stage is an important clue to solving the classic questions of astronomy: "How and when did spiral galaxies form?"

"I was excited because I had never seen such clear evidence of a rotating disk, spiral structure, and centralized mass structure in a distant galaxy in any previous ...

A new study published in the journal Science, highlights the opportunity to complement current climate mitigation scenarios with scenarios that capture the interdependence among investors' perception of future climate risk, the credibility of climate policies, and the allocation of investments across low- and high-carbon assets in the economy.

Climate mitigation scenarios are key to understanding the transition to a low-carbon economy and inform climate policies. These scenarios are also important for financial investors to assess the risk of missing out on the transition or making the transition happen too late and in a disorderly fashion. In this respect, the scenarios developed by the platform of financial authorities ...

Deaths caused by indirect effects of the pandemic emphasize the need for policy changes that address widening health and racial inequities.

More than 15 months into the pandemic, the U.S. death toll from COVID-19 is nearing 600,000. But COVID-19 deaths may be underestimated by 20%, according to a new, first-of-its-kind study from Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH), the University of Pennsylvania, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Published in the journal PLOS Medicine, the study uses data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Cornell University engineers and plant scientists have teamed up to develop a low-cost system that allows grape growers to predict their yields much earlier in the season and more accurately than costly traditional methods.

The new method allows a grower to use a smartphone to record video of grape vines while driving a tractor or walking through the vineyard at night. Growers may then upload their video to a server to process the data. The system relies on computer-vision to improve the reliability of yield estimates.

Traditional methods for estimating grape ...

INFORMS Journal Information Systems Research Study Key Takeaways:

In real-time feedback the relationship source (peer, subordinate or supervisor) plays a role: the feedback tends to be more critical when it is from supervisors.

Favoritism and retribution are impacted in real-time feedback: Supervisors adopt tit-for-tat strategies, but peers do not.

Men rate women higher than men, and women rate men and women similar to how men rate men.

Positive real-time feedback has a stronger effect on future ratings than negative feedback.

CATONSVILLE, MD, May 20, 2021 - To deliver real-time feedback to support employee development and rapid innovation, many companies are replacing formal, review-based performance management with systems that enable frequent and continuous employee evaluation. ...

Astronomers using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have traced the locations of five brief, powerful radio blasts to the spiral arms of five distant galaxies.

Called fast radio bursts (FRBs), these extraordinary events generate as much energy in a thousandth of a second as the Sun does in a year. Because these transient radio pulses disappear in much less than the blink of an eye, researchers have had a hard time tracking down where they come from, much less determining what kind of object or objects is causing them. Therefore, most of the time, astronomers don't know exactly where to look.

Locating where these blasts ...

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 22 percent of older adults in the United States suffer from a functional impairment, defined as difficulties performing daily activities, such as bathing or getting dressed, or problems with concentration or decision-making affected by physical, mental or emotional conditions.

In a new study published in the May 20, 2021 online edition of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine found that functional impairments among adults aged 50 and older are associated with a higher risk of medical cannabis use; and prescription opioid and tranquilizer/sedative use and misuse.

"Our ...