(Press-News.org) TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- New research shows that concentrations of the toxic element mercury in rivers and fjords connected to the Greenland Ice Sheet are comparable to rivers in industrial China, an unexpected finding that is raising questions about the effects of glacial melting in an area that is a major exporter of seafood.

"There are surprisingly high levels of mercury in the glacier meltwaters we sampled in southwest Greenland," said Jon Hawkings, a postdoctoral researcher at Florida State University and and the German Research Centre for Geosciences. "And that's leading us to look now at a whole host of other questions such as how that mercury could potentially get into the food chain."

The study was published today in Nature Geoscience.

The international study began as a collaboration between Hawkings and glaciologist Jemma Wadham, a professor at the University of Bristol's Cabot Institute for the Environment.

Initially, researchers sampled waters from three different rivers and two fjords next to the ice sheet to gain a better understanding of meltwater water quality from the glacier and how nutrients in these meltwaters may sustain coastal ecosystems.

One of the elements they measured for was the potentially toxic element mercury, but they had no expectation that they would find such high concentrations in the water there.

Typical dissolved mercury content in rivers are about 1 - 10 ng L-1 (the equivalent of a salt grain-sized amount of mercury in an Olympic swimming pool of water). In the glacier meltwater rivers sampled in Greenland, scientists found dissolved mercury levels in excess of 150 ng L-1, far higher than an average river. Particulate mercury carried by glacial flour (the sediment that makes glacial rivers look milky) was found in very high concentrations of more than 2000 ng L-1.

With any unusual finding, the results raise more questions than answers. Researchers are unclear if the mercury levels will dissipate farther away from the ice sheet and whether this "glacier" derived mercury is making its way into the aquatic food web, where it can often concentrate further.

"We didn't expect there would be anywhere near that amount of mercury in the glacial water there," said Associate Professor of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science Rob Spencer. "Naturally, we have hypotheses as to what is leading to these high mercury concentrations, but these findings have raised a whole host of questions that we don't have the answers to yet."

Fishing is Greenland's primary industry with the country being a major exporter of cold-water shrimp, halibut and cod.

"We've learned from many years of fieldwork at these sites in Western Greenland that glaciers export nutrients to the ocean, but the discovery that they may also carry potential toxins unveils a concerning dimension to how glaciers influence water quality and downstream communities, which may alter in a warming world and highlights the need for further investigation," Wadham said.

The finding underscores the complicated reality of rapidly melting ice sheets across the globe. About 10 percent of the Earth's land surface is covered by glaciers, and these environments are undergoing rapid change as a result of rising temperatures. Scientists worldwide are working to understand how warming temperatures -- and thus more rapidly melting glaciers -- will affect geochemical processes critical to life on Earth.

"For decades, scientists perceived glaciers as frozen blocks of water that had limited relevance to the Earth's geochemical and biological processes," Spencer said. "But we've shown over the past several years that line of thinking isn't true. This study continues to highlight that these ice sheets are rich with elements of relevance to life."

Hawkings also said it was worth noting that this source of mercury is very likely coming from the Earth itself, as opposed to a fossil fuel combustion or other industrial source. That may matter in how scientists and policymakers think about the management of mercury pollution in the future.

"All the efforts to manage mercury thus far have come from the idea that the increasing concentrations we have been seeing across the Earth system come primarily from direct anthropogenic activity, like industry," Hawkings said. "But mercury coming from climatically sensitive environments like glaciers could be a source that is much more difficult to manage."

INFORMATION:

Other scientists contributing to the study come from an international team based in the United States (USGS, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, University of California Santa Cruz, Brigham Young University) United Kingdom (University of Bristol, University of Glasgow), Czechia (Charles University), Norway (UiT The Arctic University of Norway, UiO University of Oslo), Greenland (Greenland Climate Research Centre) and the Netherlands (Royal Netherlands Institute of Sea Research).

The fieldwork was supported by grants through the Leverhulme Trust and the UKRI's Natural Environment Research Council. Jon Hawkings was also supported by a European Commission Horizon 2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions Fellowship. Part of the research was conducted at the Florida State University-headquartered National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, funded by the National Science Foundation and the state of Florida.

Plants grown in soil are colonized by diverse microbes collectively known as the plant microbiota, which is essential for optimal plant growth in nature and protects the plant host from the harmful effects of pathogenic microorganisms and insects. However, in the face of an advanced plant immune system that has evolved to recognize microbial associated-molecular patterns (MAMPs) - conserved molecules within a microbial class - and mount an immune response, it is unknown how soil-dwelling microbes are able to colonize plant roots. Now, MPIPZ researchers led by Paul Schulze-Lefert, and researchers from the University of Carolina led by Jeffery L. Dangl show, in two separate studies, that a subset ...

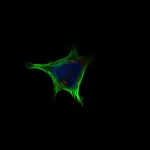

Brain tumor cells with a certain common mutation reprogram invading immune cells. This leads to the paralysis of the body's immune defense against the tumor in the brain. Researchers from Heidelberg, Mannheim, and Freiburg discovered this mechanism and at the same time identified a way of reactivating the paralyzed immune system to fight the tumor. These results confirm that therapeutic vaccines or immunotherapies are more effective against brain tumors if active substances are simultaneously used to promote the suppressed immune system.

Diffuse gliomas are usually incurable brain tumors that spread in the brain and are difficult to completely remove by surgery. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy often only have a limited ...

Scientists and clinicians at UCL and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) studying the effectiveness of CAR T-cell therapies in children with leukaemia, have discovered a small sub-set of T-cells that are likely to play a key role in whether the treatment is successful.

Researchers say 'stem cell memory T-cells' appear critical in both destroying the cancer at the outset and for long term immune surveillance and exploiting this quality could improve the design and performance of CAR T therapies.

Explaining the study, published in Nature Cancer, lead author Dr Luca Biasco (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health), said: "During clinical trials we have seen some very encouraging results in young patients with leukaemia, however it's still not clear why CAR T-cells continue ...

A population of bridled nailtail wallabies in Queensland has been brought back from the brink of extinction after conservation scientists led by UNSW Sydney successfully trialled an intervention technique never before used on land-based mammals.

Using a method known as 'headstarting', the researchers rounded up bridled nailtail wallabies under a certain size and placed them within a protected area where they could live until adulthood without the threat of their main predators - feral cats - before being released back into the wild.

In an article published today in Current Biology, the scientists describe how they decided on the strategy to protect only the juvenile wallabies from feral cats in Avocet Nature Refuge, ...

Knowledge systems outside of those sanctioned by Western universities have often been marginalised or simply not engaged with in many science disciplines, but there are multiple examples where Western scientists have claimed discoveries for knowledge that resident experts already knew and shared. This demonstrates not a lack of knowledge itself but rather that, for many scientists raised in Western society, little education concerning histories of systemic oppression has been by design. Western scientific knowledge has also been used to justify social and environmental control, including dispossessing colonised people of their ...

Our brain is usually well protected from uncontrolled influx of molecules from the periphery thanks to the blood-brain barrier, a physical seal of cells lining the blood vessel walls. The hypothalamus, however, is a notable exception to this rule. Characterized by "leaky" blood vessels, this region, located at the base of the brain, is exposed to a variety of circulating bioactive molecules. This anatomical feature also determines its function as a rheostat involved in the coordination of energy sensing and feeding behavior.

Several hormones and nutrients are known to influence the feeding neurocircuit in the hypothalamus. Classic examples are leptin and insulin, both involved in informing the brain of available energy. In the last years, the ...

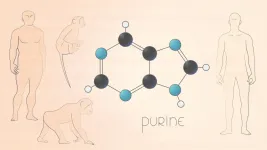

Skoltech scientists and their colleagues from Germany and the United States have analyzed the metabolomes of humans, chimpanzees, and macaques in muscle, kidney, and three different brain regions. The team discovered that the modern human genome undergoes mutation which makes the adenylosuccinate lyase enzyme less stable, leading to a decrease in purine synthesis. This mutation did not occur in Neanderthals, so the scientists believe that it affected metabolism in brain tissues and thereby strongly contributed to modern humans evolving into a separate species. The research was published in the journal eLife.

The predecessors of modern humans split from their closest evolutionary relatives, Neanderthals and Denisovans, about 600,000 ...

A new low-cost and sustainable technique would boost the possibilities for hospitals and clinics to deliver therapeutics with aerogels, a foam-like material now found in such high-tech applications as insulation for spacesuits and breathable plasters.

With the help of an ordinary kitchen freezer, this newest form of aerogel was made from all natural ingredients, including plant cellulose and algae, says Jowan Rostami, a researcher in fibre technology at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

Rostami says that the aerogel's low density and favorable surface area make it ideal for a wide range of uses, ...

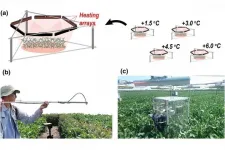

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Scientists report that it is possible to detect and predict heat damage in crops by measuring the fluorescent light signature of plant leaves experiencing heat stress. If collected via satellite, this fluorescent signal could support widespread monitoring of growth and crop yield under the heat stress of climate change, the researchers say.

Their study measures sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence - or SIF - to monitor a plant's photosynthetic health and establish a connection between heat stress and crop yield. The findings are published in the journal Global Change Biology.

Sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence occurs when a portion of photosynthetic energy, in the form of near-infrared light, is emitted from plant leaves, the researchers said.

"There ...

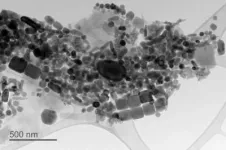

Fifty-six million years ago, as the Earth's climate warmed by five to eight degrees C, new land mammals evolved, tropical forests expanded, giant insects and reptiles appeared and the chemistry of the ocean changed. Through it all, bacteria in the ocean in what is now New Jersey kept a record of the changes in their environment through forming tiny magnetic particles. Now, those particles and their record are all that's left of these microorganisms. Thanks to new research tools, that record is finally being read.

In research published in the journal Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, researchers including University of Utah doctoral student Courtney Wagner and associate professor Peter Lippert report the climate clues that can ...