(Press-News.org) When a single gene in a cell is turned on or off, its resulting presence or absence can affect the function and survival of the cell. In a new study appearing May 24 in Nature Neuroscience, UCSF researchers have successfully catalogued this effect in the human neuron by separately toggling each of the 20,000 genes in the human genome.

In doing so, they've created a technique that can be employed for many different cell types, as well as a database where other researchers using the new technique can contribute similar knowledge, creating a picture of gene function in disease across the entire spectrum of human cells.

"This is the key next step in uncovering the mechanisms behind disease genes," said Martin Kampmann, PhD, associate professor, Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases and the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, noting that the work leverages recent advances in gene sequencing, stem cell technology, and CRISPR.

"There are lots of human genetics studies linking specific genes to specific diseases," Kampmann said. "The work we're doing can provide insight into how changes in these genes lead to disease and allow us to target them with treatments."

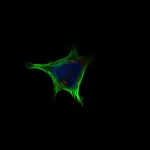

His team was interested in pinpointing genes that might be involved in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and related forms of dementia. Their approach included using stem-cell-generated human neurons and identifying chemical changes that occur in the cell when individual genes are turned on and off.

They were looking specifically for downstream changes in gene expression that would produce oxidative stress in the cell, a circumstance in which highly reactive forms of oxygen can create a toxic environment. Such conditions are thought to contribute to neurodegeneration.

Flipping gene switches reveals unexpected results

To survey individual genes and learn more about their functions, Kampmann employed a technique called CRISPR activation/interference, or CRISPR a/i, which he co-developed as a UCSF post-doctoral scholar working on cancer cells with Jonathan Weissman, PhD, a former UCSF faculty member and current Whitehead Institute member and investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. CRISPR a/i allows a researcher to temporarily turn a single gene off or on and see how that change affects the expression of other genes.

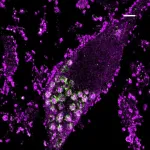

Using this tool on the human neuron, Kampmann turned one gene after another on and off, using a dye to visualize the presence of highly reactive oxygen. Among the most interesting of his findings was that switching off the gene for a protein called prosaposin, which normally assists with the cell's recycling of waste products, greatly increased the levels of oxidative stress.

In neurons, prosaposin is associated with a part of the cell called the lysosome, where biological molecules and toxins are sorted through and dealt with in a variety of ways. "At first glance, prosaposin should have nothing to do with oxidative molecules. It caught our attention because this gene had recently been linked to Parkinson's disease," Kampmann said. "What was really exciting was that now, with the results from this CRISPR screen, we had a cell-based model to help us understand what's behind that linkage."

The team then embarked on what Kampmann called a "detective story" to find out how the lack of prosaposin is linked to neurodegeneration. The researchers found that suppression of the gene led to buildup of a substance called age pigment, which has been seen in aging cells whose lysosomes no longer degrade material as efficiently. The researchers discovered that age pigment trapped iron, generating reactive oxygen molecules that triggered ferroptosis, an iron-dependent process that leads to cell death.

"By simply inactivating a single gene," Kampmann said, "in only days we could generate a hallmark of aging that would normally take decades to develop in the human body."

Building a global database of gene function

Kampmann's genetic screen is the first of its kind performed on human neurons.

The cascade of changes he observed are specific to the function of neurons and are related to just one set of conditions. He said the results make a case for using CRISPR a/i to perform similar screens looking for changes that prompt other kinds of disease-related environments in neurons and other types of differentiated cells.

To that end, Kampmann has created an open-access database called CRISPRbrain, where he and other scientists can share and study large-scale data sets like the ones generated by his genetic screens. Applying advanced computational technology such as machine learning can then detect patterns in this sea of data.

"By becoming the data commons for screens of many different cell types from many different labs and in different disease contexts, we can achieve a critical mass of information," he said. "There's enormous power in aggregating and cross-analyzing all of this."

The team's next step is to perform similar screens on neurons made from stem cells derived from patients with mutations known to contribute to neurodegeneration, as well as look at other cells such as astrocytes and microglia that play roles in brain disease.

Kampmann's hope is that the technology and database are widely adopted. "Now that we can do this in a systematic way, we can really interpret the underlying processes of how genes contribute to disease and find pathways to treat those conditions."

INFORMATION:

Authors: Authors include Ruilin Tian, PhD, Anthony Abarientos, BA, Jason Hong, BS, Nina Draeger, PhD, and Kun Leng, PhD from UCSF. For additional authors, please see the paper.

Funding: This research was supported by NIH/ NIGMS grants DP2 GM119139 and DP2GM132681, NIH/NIA grants R01 AG062359 and R56 AG057528, F30 AG066418, NIH/NINDS grant U54 NS100717, and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, part of the Department of Health and Human Services (project number ZIA AG000957-16). For additional funding information, please see the paper.

Disclosures: M.K. has filed a patent application related to CRISPRi and CRISPRa screening (PCT/US15/40449) and serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Engine Biosciences, Casma Therapeutics, and Cajal Neuroscience.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at END

New research from Florida State University shows that concentrations of the toxic element mercury in rivers and fjords connected to the Greenland Ice Sheet are comparable to rivers in industrial China, an unexpected finding that is raising questions about the effects of glacial melting in an area that is a major exporter of seafood.

"There are surprisingly high levels of mercury in the glacier meltwaters we sampled in southwest Greenland," said FSU postdoctoral fellow Jon Hawkings. "And that's leading us to look now at a whole host of other questions such as how that mercury could potentially get into the food chain."

The study was published today in Nature Geoscience.

Initially, researchers sampled waters from three different ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- New research shows that concentrations of the toxic element mercury in rivers and fjords connected to the Greenland Ice Sheet are comparable to rivers in industrial China, an unexpected finding that is raising questions about the effects of glacial melting in an area that is a major exporter of seafood.

"There are surprisingly high levels of mercury in the glacier meltwaters we sampled in southwest Greenland," said Jon Hawkings, a postdoctoral researcher at Florida State University and and the German Research Centre for Geosciences. ...

Plants grown in soil are colonized by diverse microbes collectively known as the plant microbiota, which is essential for optimal plant growth in nature and protects the plant host from the harmful effects of pathogenic microorganisms and insects. However, in the face of an advanced plant immune system that has evolved to recognize microbial associated-molecular patterns (MAMPs) - conserved molecules within a microbial class - and mount an immune response, it is unknown how soil-dwelling microbes are able to colonize plant roots. Now, MPIPZ researchers led by Paul Schulze-Lefert, and researchers from the University of Carolina led by Jeffery L. Dangl show, in two separate studies, that a subset ...

Brain tumor cells with a certain common mutation reprogram invading immune cells. This leads to the paralysis of the body's immune defense against the tumor in the brain. Researchers from Heidelberg, Mannheim, and Freiburg discovered this mechanism and at the same time identified a way of reactivating the paralyzed immune system to fight the tumor. These results confirm that therapeutic vaccines or immunotherapies are more effective against brain tumors if active substances are simultaneously used to promote the suppressed immune system.

Diffuse gliomas are usually incurable brain tumors that spread in the brain and are difficult to completely remove by surgery. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy often only have a limited ...

Scientists and clinicians at UCL and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) studying the effectiveness of CAR T-cell therapies in children with leukaemia, have discovered a small sub-set of T-cells that are likely to play a key role in whether the treatment is successful.

Researchers say 'stem cell memory T-cells' appear critical in both destroying the cancer at the outset and for long term immune surveillance and exploiting this quality could improve the design and performance of CAR T therapies.

Explaining the study, published in Nature Cancer, lead author Dr Luca Biasco (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health), said: "During clinical trials we have seen some very encouraging results in young patients with leukaemia, however it's still not clear why CAR T-cells continue ...

A population of bridled nailtail wallabies in Queensland has been brought back from the brink of extinction after conservation scientists led by UNSW Sydney successfully trialled an intervention technique never before used on land-based mammals.

Using a method known as 'headstarting', the researchers rounded up bridled nailtail wallabies under a certain size and placed them within a protected area where they could live until adulthood without the threat of their main predators - feral cats - before being released back into the wild.

In an article published today in Current Biology, the scientists describe how they decided on the strategy to protect only the juvenile wallabies from feral cats in Avocet Nature Refuge, ...

Knowledge systems outside of those sanctioned by Western universities have often been marginalised or simply not engaged with in many science disciplines, but there are multiple examples where Western scientists have claimed discoveries for knowledge that resident experts already knew and shared. This demonstrates not a lack of knowledge itself but rather that, for many scientists raised in Western society, little education concerning histories of systemic oppression has been by design. Western scientific knowledge has also been used to justify social and environmental control, including dispossessing colonised people of their ...

Our brain is usually well protected from uncontrolled influx of molecules from the periphery thanks to the blood-brain barrier, a physical seal of cells lining the blood vessel walls. The hypothalamus, however, is a notable exception to this rule. Characterized by "leaky" blood vessels, this region, located at the base of the brain, is exposed to a variety of circulating bioactive molecules. This anatomical feature also determines its function as a rheostat involved in the coordination of energy sensing and feeding behavior.

Several hormones and nutrients are known to influence the feeding neurocircuit in the hypothalamus. Classic examples are leptin and insulin, both involved in informing the brain of available energy. In the last years, the ...

Skoltech scientists and their colleagues from Germany and the United States have analyzed the metabolomes of humans, chimpanzees, and macaques in muscle, kidney, and three different brain regions. The team discovered that the modern human genome undergoes mutation which makes the adenylosuccinate lyase enzyme less stable, leading to a decrease in purine synthesis. This mutation did not occur in Neanderthals, so the scientists believe that it affected metabolism in brain tissues and thereby strongly contributed to modern humans evolving into a separate species. The research was published in the journal eLife.

The predecessors of modern humans split from their closest evolutionary relatives, Neanderthals and Denisovans, about 600,000 ...

A new low-cost and sustainable technique would boost the possibilities for hospitals and clinics to deliver therapeutics with aerogels, a foam-like material now found in such high-tech applications as insulation for spacesuits and breathable plasters.

With the help of an ordinary kitchen freezer, this newest form of aerogel was made from all natural ingredients, including plant cellulose and algae, says Jowan Rostami, a researcher in fibre technology at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

Rostami says that the aerogel's low density and favorable surface area make it ideal for a wide range of uses, ...