Icebergs push back

Slushy iceberg aggregates control calving timing on Greenland's Jakobshavn Isbræ

2021-05-27

(Press-News.org) Shortly before Jakobshavn Isbræ, a tidewater glacier in Greenland, calves massive chunks of ice into the ocean, there's a sudden change in the slushy collection of icebergs floating along the glacier's terminus, according to a new paper led by the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at CU Boulder. The work, published in Nature Geoscience, shows that a relaxation in the thick aggregate of icebergs floating at the glacier-ocean boundary occurs up to an hour before calving events. This finding may help scientists better understand future sea-level rise scenarios and could also help them predict when major episodes of calving are about to occur.

In winter months, icebergs and sea ice accumulate within the fjord in front of Jakobshavn Isbræ, forming a frozen plug that prevents calving. The glacier can continue to flow into the fjord, intact, and advance dozens of meters each day. This accumulation of icy material, which scientists refer to as ice mélange, persists into the summer, but its shelf-like structure loses rigidity in the relative warmth, and it behaves more like individual icebergs jammed together in the fjord. Until now, no study has shown whether this type of late summer ice mélange can influence iceberg calving.

"It only takes a small bit of strain for the mélange to stretch or relax a little bit, and so it's no longer an ice jam," said Ryan Cassotto, a researcher in CIRES' Earth Science and Observation Center and lead author of the new study.

To understand what was happening during these calving events, Cassotto and his colleagues took ground-based radar interferometers to Greenland in 2012 and set them up in Jakobshavn Isbræ's proglacial fjord to record iceberg interactions every three minutes. They found that in between calving events, icebergs within the ice mélange moved together, flowing down the fjord as a single, cohesive unit.

But the movement of individual icebergs changed just before each of the 14 calving events that they observed--instead of flowing as a single, coherent unit, the ice mélange relaxed and icebergs began to move independently of each other.

"When the ice mélange relaxes, individual icebergs begin to rotate around, and when they begin to rotate around, the mélange loses its structure," said Cassotto. "And when it loses its structure, it loses its ability to impede calving."

To understand what was happening to the icebergs within the ice mélange during these events, the researchers used a particle dynamics model that simulates the movement of individual icebergs. They found that only a small downfjord expansion of the ice mélange was needed to trigger independent movement of the icebergs.

"As a gateway to the ocean, ice mélange can have a direct impact on future predictions of seal-level rise," said Justin Burton, associate professor of physics at Emory University and co-author of the paper. "We've provided the best, most precise data ever showing the processes leading up to major calving events. That helps us understand the forces determining how much ice discharges into the ocean, and how fast it happens."

The exact cause of such shifts is not yet clear, but changes in ocean tides, the subglacial discharge of meltwater, and winds may help explain the sudden relaxation of the thick aggregate of icebergs pushing back against the glacier.

This study is the first to show that an ice mélange largely free of sea ice can control the timing of calving, Cassotto said. It is also the first study in which researchers were able to observe granular scale changes in a material within the natural environment.

"Most studies of granular materials are conducted in laboratories," said Jason Amundson, associate professor of geophysics at the University of Alaska Southeast and co-author of the paper. "These observations demonstrate that we can gain new insights into the behavior of granular materials by studying dense packs of icebergs, which represent some of the largest granular materials on Earth" The methods in this study could be used to predict failure in other geophysical materials, such as debris flow or landslides.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-27

Since its discovery in the 1960s, the Jebel Sahaba cemetery (Nile Valley, Sudan), 13 millennia old, was considered to be one of the oldest testimonies to prehistoric warfare. However, scientists from the CNRS and the University of Toulouse - Jean Jaurès (1) have re-analysed the bones preserved in the British Museum (London) and re-evaluated their archaeological context. The results, published in Scientific Reports on May 27, 2021, show that it was not a single armed conflict but rather a succession of violent episodes, probably exacerbated by climate change.

Many individuals buried at Jebel Sahaba bear injuries, half ot them caused by projectiles, the points of which were found in the bones or the fill where the body was located. The ...

2021-05-27

What The Study Did: The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that enhanced personal protective equipment is associated with low rates of SARS-CoV-2 transmission during tracheostomy.

Authors: Phillip Staibano, M.Sc., M.D., of McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2021.0930)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial ...

2021-05-27

What The Study Did: This survey study of adults living Michigan during the COVID-19 pandemic examines associations between race/ethnicity, medical mistrust within racial/ethnic groups and willingness to participate in COVID-19 vaccine trials or to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.

Authors: Hayley S. Thompson, Ph.D., of the Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11629)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, ...

2021-05-27

What The Study Did: In this study of 1,597 Big Ten athletes who had comprehensive cardiac screening, including cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging, after COVID-19 infection, 37 athletes (2.3%) were diagnosed with clinical and subclinical myocarditis. Researchers report CMR screening increased detection of myocarditis, a leading cause of sudden death in competitive athletes.

Authors: Curt J.Daniels, M.D., and Saurabh Rajpal, M.B.B.S., M.D., of Ohio State University in Columbus, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2065)

Editor's ...

2021-05-27

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Nitrogen, an element that is essential for all living cells, makes up about 78 percent of Earth's atmosphere. However, most organisms cannot make use of this nitrogen until it is converted into ammonia. Until humans invented industrial processes for ammonia synthesis, almost all ammonia on the planet was generated by microbes using nitrogenases, the only enzymes that can break the nitrogen-nitrogen bond found in gaseous dinitrogen, or N2.

These enzymes contain clusters of metal and sulfur atoms that help perform this critical reaction, but the mechanism of how they do so is not well-understood. For the first time, MIT chemists have now determined the structure of a complex that forms when N2 binds to these clusters, and they discovered that the clusters are able to weaken ...

2021-05-27

A massive genome-wide association study (GWAS) of genetic and health records of 1.2 million people from four separate data banks has identified 178 gene variants linked to major depression, a disorder that will affect one of every five people during their lifetimes.

The results of the study, led by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (V.A.) researchers at Yale University School of Medicine and University of California-San Diego (UCSD), may one day help identify people most at risk of depression and related psychiatric disorders and help doctors prescribe drugs best suited to treat the disorder.

The study was published May 27 in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

For the ...

2021-05-27

The research - by the University of York - gives scientists a new tool that will support the development of new varieties.

The research led to scientists being able to develop an adaptable framework for describing gene content and order across all Brassica species.

Lead author, Professor Ian Bancroft, Chair of Plant Genomics at the Centre for Novel Agricultural Products (CNAP), at the Department of Biology said: "The research has helped us understand the trajectory of how genomes evolve in brassicas. We can use this new knowledge, for example, to accelerate the exchange of beneficial genes between Brassica species."

Brassica vegetables, such as broccoli, cabbage, kale, pak choi and swede, along with brassica oil crops such as ...

2021-05-27

Swiftness is essential when treating lung cancer, the second most common type of cancer in the U.S. and the country's leading cause of cancer deaths. For patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer, surgical removal of a tumor-infested lung or of a smaller lung section may be the only treatment needed.

However, some patients postpone surgery while seeking second opinions, because of economic or social factors, or for personal reasons such as waiting until after a child's wedding or a planned vacation. Worries about contracting COVID-19 in a clinical setting also have led to delays.

But a new study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine ...

2021-05-27

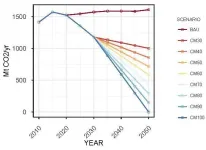

With the COP Climate conference in Glasgow only a few months away, the ambitions of the Paris Agreement and the importance of taking action at the national level to reach global climate goals is returning to the spotlight. IIASA researchers and colleagues have proposed a novel systematic and independent scenario framework that could help policymakers assess and compare climate policies and long-term strategies across countries to support coordinated global climate action.

The Paris Agreement defines a long-term temperature goal for international climate policy: "holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C". Its achievement critically ...

2021-05-27

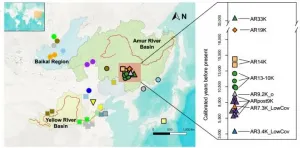

A study led by research groups of Prof. FU Qiaomei from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Prof. ZHANG Hucai from Yunnan University covers the largest temporal transect of population dynamics in East Asia so far and offers a clearer picture of the deep population history of northern East Asia.

The study was published in Cell on May 27.

Northern East Asia falls within a similar latitude range as central and southern Europe, where human population movements and size were influenced by Ice Age climatic fluctuations. Did these climatic fluctuations have an impact on the population history of northern East Asia?

Stories uncovered by ancient DNA in East Asia remain relatively underexplored. The population ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Icebergs push back

Slushy iceberg aggregates control calving timing on Greenland's Jakobshavn Isbræ