Using fossil plant molecules to track down the Green Sahara

New publication: Researchers explain how vegetation was possible in the desert

2021-05-31

(Press-News.org) The Sahara has not always been covered by only sand and rocks. During the period from 14,500 to 5,000 years ago large areas of North Africa were more heavily populated, and where there is desert today the land was green with vegetation. This is evidenced by various sites with rock paintings showing not only giraffes and crocodiles, but even illustrating people swimming in the "Cave of Swimmers". This period is known as the Green Sahara or African Humid Period. Until now, researchers have assumed that the necessary rain was brought from the tropics through an enhanced summer monsoon. The northward shift of the monsoon was attributed to rotation of the Earth's tilted axis that produces higher levels of solar radiation over North Africa approximately every 25,000 years. However, climate models have not been able to simulate plant growth sufficient to create a Green Sahara with rain that stem only from the summer monsoon. Scientists are convinced that permanent vegetation at that time in North Africa cannot be explained by a single rainy season each year.

Dr. Enno Schefuß of MARUM and Dr. Rachid Cheddadi of the University of Montpellier (France) together with an international team of researchers have analyzed pollen and leaf waxes extracted from a sediment core in order to reconstruct the vegetation cover and amount of rainfall in the past. The core was retrieved from Lake Tislit in the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco. Fossil components of plants such as pollen and refractory plant molecules are deposited in lakes just as in marine sediments. These enable to identify the types of vegetation and climate conditions from the past.

"Our results are very clear," explains Enno Schefuß, "While the leaf waxes indicate increased rainfall during the African Humid Period, the pollen explicitly reveal that the vegetation was Mediterranean, not subtropical or even tropical." Mediterranean plants can tolerate arid conditions in the summer as long as they receive sufficient rain in the winter. "This strongly suggests that the monsoon reconstructions of previous studies need to be reconsidered."

Based on these findings, Schefuß and his colleagues have developed a new concept to explain the Green Sahara. During the period of the Green Sahara, as the monsoon was intensifying and moving northward in the summer, there must have been a southward shift of the belt of westerlies in the winter that brought winter precipitation to North Africa. The team subsequently tested their past climate reconstructions from the Tislit record using a mechanistic vegetation model. "We have winter rain on the northern margin of the Sahara, the monsoon on the southern margin, and between the two areas an overlap of the two rain systems which provides rains there during both summer and winter, albeit rather sparsely," explains Rachid Cheddadi. The vegetation model simulations clearly showed that a Green Sahara was formed under this climate scenario. A continuous vegetation cover could only form with precipitation in two seasons; the plants would not survive a long dry phase after a short rainy period.

Schefuß and his colleagues describe their results as a paradigm change in the climate research explaining the cause of the Green Sahara. The implications of this include not only a better understanding of past climate conditions, but also an improvement of the predictions for future climate and vegetation trends in the region, as well a contribution to archaeological studies of settlement patterns and migration routes.

A planned expedition using the Research Vessel METEOR to retrieve additional high-resolution sediment archives from the near-coastal deposits off Morocco was postponed due to the CoVid-19 pandemic. However, it will be rescheduled as soon as possible in order to further strengthen this research and the German-Moroccan cooperation.

INFORMATION:

Original publication:

Rachid Cheddadi, Matthieu Carré, Majda Nourelbait, Louis François, Ali Rhoujjati, Roger Manay, Diana Ochoa, Enno Schefuß: Early Holocene greening of the Sahara requires Mediterranean winter rainfall. PNAS 2021.

Contakt:

Dr. Enno Schefuß

Phone: +49 421 218 65526

Email: eschefuss@marum.de

MARUM produces fundamental scientific knowledge about the role of the ocean and the seafloor in the total Earth system. The dynamics of the oceans and the seabed significantly impact the entire Earth system through the interaction of geological, physical, biological and chemical processes. These influence both the climate and the global carbon cycle, resulting in the creation of unique biological systems. MARUM is committed to fundamental and unbiased research in the interests of society, the marine environment, and in accordance with the sustainability goals of the United Nations. It publishes its quality-assured scientific data to make it publicly available. MARUM informs the public about new discoveries in the marine environment and provides practical knowledge through its dialogue with society. MARUM cooperation with companies and industrial partners is carried out in accordance with its goal of protecting the marine environment.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-31

An emotion regulation strategy known as cognitive reappraisal helped reduce the typically heightened and habitual attention to drug-related cues and contexts in cocaine-addicted individuals, a study by Mount Sinai researchers has found. In a paper published in PNAS, the team suggested that this form of habit disruption, mediated by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain, could play an important role in reducing the compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse that are the hallmarks, and long-standing challenges, of addiction.

"Relapse in addiction is often precipitated by heightened attention-bias to drug-related cues, which could consist of sights, smells, ...

2021-05-31

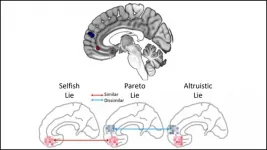

You may think a little white lie about a bad haircut is strictly for your friend's benefit, but your brain activity says otherwise. Distinct activity patterns in the prefrontal cortex reveal when a white lie has selfish motives, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

White lies -- formally called Pareto lies -- can benefit both parties, but their true motives are encoded by the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). This brain region computes the value of different social behaviors, with some subregions focusing on internal motivations and others on external ones. Kim and Kim predicted activity patterns in these subregions could elucidate the true motive behind white lies.

The research team deployed a stand in for white lies, having participants tell lies to earn a reward ...

2021-05-31

By including multi-ethnic participants, a largescale genetic study has identified more regions of the genome linked to type 2 diabetes-related traits than if the research had been conducted in Europeans alone.

The international MAGIC collaboration, made up of more than 400 global academics, conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis led by the University of Exeter. Now published in Nature Genetics, their findings demonstrate that expanding research into different ancestries yields more and better results, as well as ultimately benefitting global patient care.

Up to now, nearly 87 per cent of ...

2021-05-31

Artificial intelligence promises to be a powerful tool for improving the speed and accuracy of medical decision-making to improve patient outcomes. From diagnosing disease, to personalizing treatment, to predicting complications from surgery, AI could become as integral to patient care in the future as imaging and laboratory tests are today.

But as University of Washington researchers discovered, AI models -- like humans -- have a tendency to look for shortcuts. In the case of AI-assisted disease detection, these shortcuts could lead to diagnostic errors if deployed in clinical settings.

In a new paper published May 31 in Nature Machine Intelligence, ...

2021-05-31

The Water Oxidation Reaction (WOR) is one of the most important reactions on the planet since it is the source of nearly all the atmosphere's oxygen. Understanding its intricacies can hold the key to improve the efficiency of the reaction. Unfortunately, the reaction's mechanisms are complex and the intermediates highly unstable, thus making their isolation and characterisation extremely challenging. To overcome this, scientists are using molecular catalysts as models to understand the fundamental aspects of water oxidation - particularly the oxygen-oxygen bond-forming reaction.

For the first time, scientists in ICIQ's ...

2021-05-31

Between 1991 and 2018, more than a third of all deaths in which heat played a role were attributable to human-induced global warming, according to a new article in Nature Climate Change.

The study, the largest of its kind, was led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and the University of Bern within the Multi-Country Multi-City (MCC) Collaborative Research Network. Using data from 732 locations in 43 countries around the world it shows for the first time the actual contribution of man-made climate change in increasing mortality risks due to heat.

Overall, ...

2021-05-31

In a study of 11 medical-mystery patients, an international team of researchers led by scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the Uniformed Services University (USU) discovered a new and unique form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Unlike most cases of ALS, the disease began attacking these patients during childhood, worsened more slowly than usual, and was linked to a gene, called SPTLC1, that is part of the body's fat production system. Preliminary results suggested that genetically silencing SPTLC1 activity would be an effective strategy for combating this type of ALS.

"ALS is a paralyzing ...

2021-05-31

LOS ANGELES (May 31, 2021) -- Today The Lundquist Institute announced that its investigators contributed data from several studies, including data on Hispanics, African-Americans and East Asians, to the international MAGIC collaboration, composed of more than 400 global academics, who conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis led by the University of Exeter. Now published in Nature Genetics, their findings demonstrate that expanding research into different ancestries yields more and better results, as well as ultimately benefitting global patient care. Up to now nearly 87 percent of genomic research of this type has been conducted in Europeans. ...

2021-05-31

Pollution from manufacturing is now widespread, affecting all regions in the world, with serious ecological, economic, and political consequences. Heightened public concern and scrutiny have led to numerous governments considering policies that aim to lower pollution and improve environmental qualities. Inter-governmental agreements such as the Paris Agreement and the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals all focus on lowering emissions of pollution. Specifically, they aim to achieve a "zero-emission society," which means that pollution is cleaned up as it is produced, while also reducing pollution (This idea of dealing with pollution is referred to as the "kindergarten rule.")

Of course, any efforts to achieve this ...

2021-05-31

The use of many chemical fumigants in agriculture have been demonstrated to be harmful to human health and the environment and therefore banned from use.

Now, in an effort to reduce waste from the agricultural industry and reduce the amounts of harmful chemicals used, researchers have investigated using organic byproducts from beer production and farming as a potential method to disinfest soils, preserve healthy soil microorganisms and increase crop yields.

In this study published to Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, researchers from the Neiker Basque Institute for Agricultural Research and Development in Spain investigated using agricultural by-products rapeseed cake and beer bagasse (spent beer grains), along with fresh cow manure as two organic biodisinfestation ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Using fossil plant molecules to track down the Green Sahara

New publication: Researchers explain how vegetation was possible in the desert