Newly discovered African 'climate seesaw' drove human evolution

2021-05-31

(Press-News.org) While it is widely accepted that climate change drove the evolution of our species in Africa, the exact character of that climate change and its impacts are not well understood. Glacial-interglacial cycles strongly impact patterns of climate change in many parts of the world, and were also assumed to regulate environmental changes in Africa during the critical period of human evolution over the last ~1 million years. The ecosystem changes driven by these glacial cycles are thought to have stimulated the evolution and dispersal of early humans.

A paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) this week challenges this view. Dr. Kaboth-Bahr and an international group of multidisciplinary collaborators identified ancient El Niño-like weather patterns as the drivers of major climate changes in Africa. This allowed the group to re-evaluate the existing climatic framework of human evolution.

Walking with the rain

Dr. Kaboth-Bahr and her colleagues integrated 11 climate archives from all across Africa covering the past 620 thousand years to generate a comprehensive spatial picture of when and where wet or dry conditions prevailed over the continent. "We were surprised to find a distinct climatic east-west 'seesaw' very akin to the pattern produced by the weather phenomena of El Niño, that today profoundly influences precipitation distribution in Africa," explains Dr. Kaboth-Bahr, who led the study.

The authors infer that the effects of the tropical Pacific Ocean on the so-called "Walker Circulation" - a belt of convection cells along the equator that impact the rainfall and aridity of the tropics - were the prime driver of this climate seesaw. The data clearly shows that the wet and dry regions shifted between the east and west of the African continent on timescales of approximately 100,000 years, with each of the climatic shifts being accompanied by major turnovers in flora and mammal fauna.

"This alternation between dry and wet periods appeared to have governed the dispersion and evolution of vegetation as well as mammals in eastern and western Africa," explains Dr. Kaboth-Bahr. "The resultant environmental patchwork was likely to have been a critical component of human evolution and early demography as well."

The scientists are keen to point that although climate change was certainly not the sole factor driving early human evolution, the new study nevertheless provides a novel perspective on the tight link between environmental fluctuations and the origin of our early ancestors.

"We see many species of pan-African mammals whose distributions match the patterns we identify, and whose evolutionary history seems to articulate with the wet-dry oscillations between eastern and western Africa," adds Dr. Eleanor Scerri, one of the co-authors and an evolutionary archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany. "These animals preserve the signals of the environments that humans evolved in, and it seems likely that our human ancestors may have been similarly subdivided across Africa as they were subject to the same environmental pressures."

Ecotones: the transitional regions between different ecological zones

The scientists' work suggests that a seesaw-like pattern of rainfall alternating between eastern and western Africa probably had the effect of creating critically important ecotonal regions - the buffer zones between different ecological zones, such grassland and forest.

"Ecotones provided diverse, resource-rich and stable environmental settings thought to have been important to early modern humans," adds Dr. Kaboth-Bahr. "They certainly seem to have been important to other faunal communities."

To the scientists, this suggests that Africa's interior regions may have been critically important for fostering long-term population continuity. "We see the archaeological signatures of early members of our species all across Africa," says Dr. Scerri, "but innovations come and go and are often re-invented, suggesting that our deep population history saw a constant saw-tooth like pattern of local population growth and collapse. Ecotonal regions may have provided areas for longer term population continuity, ensuring that the larger human population kept going, even if local populations often went extinct."

"Re-evaluating these patterns of stasis, change and extinction through a new climatic framework will yield new insights into the deep human past," says Dr. Kaboth Bahr. "This does not mean that people were helpless in the face of climatic changes, but shifting habitat availability would certainly have impacted patterns of demography, and ultimately the genetic exchanges that underpin human evolution."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-31

The Sahara has not always been covered by only sand and rocks. During the period from 14,500 to 5,000 years ago large areas of North Africa were more heavily populated, and where there is desert today the land was green with vegetation. This is evidenced by various sites with rock paintings showing not only giraffes and crocodiles, but even illustrating people swimming in the "Cave of Swimmers". This period is known as the Green Sahara or African Humid Period. Until now, researchers have assumed that the necessary rain was brought from the tropics through an enhanced summer monsoon. The northward shift of the monsoon was attributed to rotation of the Earth's tilted axis that produces higher levels of ...

2021-05-31

An emotion regulation strategy known as cognitive reappraisal helped reduce the typically heightened and habitual attention to drug-related cues and contexts in cocaine-addicted individuals, a study by Mount Sinai researchers has found. In a paper published in PNAS, the team suggested that this form of habit disruption, mediated by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain, could play an important role in reducing the compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse that are the hallmarks, and long-standing challenges, of addiction.

"Relapse in addiction is often precipitated by heightened attention-bias to drug-related cues, which could consist of sights, smells, ...

2021-05-31

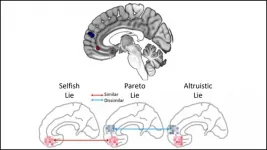

You may think a little white lie about a bad haircut is strictly for your friend's benefit, but your brain activity says otherwise. Distinct activity patterns in the prefrontal cortex reveal when a white lie has selfish motives, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

White lies -- formally called Pareto lies -- can benefit both parties, but their true motives are encoded by the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). This brain region computes the value of different social behaviors, with some subregions focusing on internal motivations and others on external ones. Kim and Kim predicted activity patterns in these subregions could elucidate the true motive behind white lies.

The research team deployed a stand in for white lies, having participants tell lies to earn a reward ...

2021-05-31

By including multi-ethnic participants, a largescale genetic study has identified more regions of the genome linked to type 2 diabetes-related traits than if the research had been conducted in Europeans alone.

The international MAGIC collaboration, made up of more than 400 global academics, conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis led by the University of Exeter. Now published in Nature Genetics, their findings demonstrate that expanding research into different ancestries yields more and better results, as well as ultimately benefitting global patient care.

Up to now, nearly 87 per cent of ...

2021-05-31

Artificial intelligence promises to be a powerful tool for improving the speed and accuracy of medical decision-making to improve patient outcomes. From diagnosing disease, to personalizing treatment, to predicting complications from surgery, AI could become as integral to patient care in the future as imaging and laboratory tests are today.

But as University of Washington researchers discovered, AI models -- like humans -- have a tendency to look for shortcuts. In the case of AI-assisted disease detection, these shortcuts could lead to diagnostic errors if deployed in clinical settings.

In a new paper published May 31 in Nature Machine Intelligence, ...

2021-05-31

The Water Oxidation Reaction (WOR) is one of the most important reactions on the planet since it is the source of nearly all the atmosphere's oxygen. Understanding its intricacies can hold the key to improve the efficiency of the reaction. Unfortunately, the reaction's mechanisms are complex and the intermediates highly unstable, thus making their isolation and characterisation extremely challenging. To overcome this, scientists are using molecular catalysts as models to understand the fundamental aspects of water oxidation - particularly the oxygen-oxygen bond-forming reaction.

For the first time, scientists in ICIQ's ...

2021-05-31

Between 1991 and 2018, more than a third of all deaths in which heat played a role were attributable to human-induced global warming, according to a new article in Nature Climate Change.

The study, the largest of its kind, was led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and the University of Bern within the Multi-Country Multi-City (MCC) Collaborative Research Network. Using data from 732 locations in 43 countries around the world it shows for the first time the actual contribution of man-made climate change in increasing mortality risks due to heat.

Overall, ...

2021-05-31

In a study of 11 medical-mystery patients, an international team of researchers led by scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the Uniformed Services University (USU) discovered a new and unique form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Unlike most cases of ALS, the disease began attacking these patients during childhood, worsened more slowly than usual, and was linked to a gene, called SPTLC1, that is part of the body's fat production system. Preliminary results suggested that genetically silencing SPTLC1 activity would be an effective strategy for combating this type of ALS.

"ALS is a paralyzing ...

2021-05-31

LOS ANGELES (May 31, 2021) -- Today The Lundquist Institute announced that its investigators contributed data from several studies, including data on Hispanics, African-Americans and East Asians, to the international MAGIC collaboration, composed of more than 400 global academics, who conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis led by the University of Exeter. Now published in Nature Genetics, their findings demonstrate that expanding research into different ancestries yields more and better results, as well as ultimately benefitting global patient care. Up to now nearly 87 percent of genomic research of this type has been conducted in Europeans. ...

2021-05-31

Pollution from manufacturing is now widespread, affecting all regions in the world, with serious ecological, economic, and political consequences. Heightened public concern and scrutiny have led to numerous governments considering policies that aim to lower pollution and improve environmental qualities. Inter-governmental agreements such as the Paris Agreement and the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals all focus on lowering emissions of pollution. Specifically, they aim to achieve a "zero-emission society," which means that pollution is cleaned up as it is produced, while also reducing pollution (This idea of dealing with pollution is referred to as the "kindergarten rule.")

Of course, any efforts to achieve this ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Newly discovered African 'climate seesaw' drove human evolution