(Press-News.org) As anyone who has ever procrastinated knows, remembering that you need to do something and acting on that knowledge are two different things. To understand how learning changes nerve cells and leads to different behaviors, researchers studied the much simpler nervous system of worms.

"In this study, we can now translate neuronal activity to behavioral response," said Project Researcher Hirofumi Sato, a neuroscientist at the University of Tokyo and first author of the research paper recently published in Cell Reports.

The discovery was made possible using technology that researchers describe as a "robot microscope," first developed in 2019 by researchers at Tohoku University in Miyagi Prefecture, northeastern Japan.

The technique involves genetically modifying the worms to add fluorescent tags onto specific molecules. The microscope then detects and tracks the fluorescent light as a worm crawls around, meaning researchers can watch chemical signals travel through and between individual neurons in awake, unrestrained animals.

The worms used in research studies, C. elegans, don't eat pure salt, but researchers can train worms to associate high or low salt levels in their environment with food. When transferred to any new environment, trained worms will begin searching for food using salt levels as a clue about which direction they should go. For example, if worms learned to expect food in high-salt areas but they notice that salt levels are decreasing as they travel, the worms will stop and change directions to try to find a higher salt level. With additional training, worms can also learn the opposite food-salt level association.

Neuroplasticity, or the brain's ability to change and "rewire" neurons, is essential for any learned behavior. The mystery for the scientific community is how different environmental clues (high or low salt) can lead to the same physical behavior (stop and change direction).

"Many animals show this flexible learned behavior pattern, so we want to understand the mechanism," said Sato.

This type of behavior requires a sensory neuron (which detects salt), motor neurons (which control movement) and interneurons (which communicate between the other two types). Although C. elegans only have 302 neurons in their entire 1-centimeter-long bodies, these same types of neurons exist in humans and communicate using the same signal molecule.

Specifically, that signal molecule is glutamate, widely recognized as one of the brain's most important signaling molecules.

"We know that if there is a defect in glutamate signaling, that might cause Alzheimer's disease or other neuronal diseases," said Sato.

The UTokyo team's new data found two different types of glutamate receptors on the same interneuron are involved in the worms' behavior. Both inhibitory and excitatory glutamate receptors respond in the same pattern, but at different intensities based on whether the worms had learned to seek high or low salt concentrations.

The exact mechanism controlling the motor neuron's signals to the interneuron's glutamate receptors remains unclear. However, this is one of the first documentations of glutamate signaling between sensory and interneurons showing experience-dependent plasticity.

Future research will continue to investigate exactly how the sensory neuron and interneuron communicate.

INFORMATION:

Research Publication

Hirofumi Sato, Hirofumi Kunitomo, Xianfeng Fei, Koichi Hashimoto, and Yuichi Iino. 25 May 2021. Glutamate signaling from a single sensory neuron mediates experience-dependent bidirectional behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Reports. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109177

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109177

Related Links

Iino Laboratory: http://molecular-ethology.bs.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/labHP/E/ETop.html

Department of Biological Sciences: http://www.bs.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/english/

Graduate School of Science: https://www.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/

Research Contact

Project Researcher Hirofumi Sato

Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, 113-0033 Tokyo, Japan

Email: hisato@bs.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Press Officer Contact

Ms. Caitlin Devor

Division for Strategic Public Relations, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 133-8654, JAPAN

Tel: +81-080-9707-8178

Email: press-releases.adm@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan's leading university and one of the world's top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world's top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at http://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ or follow us on Twitter at @UTokyo_News_en.

A team of scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology and the GEOMAR - Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel have been studying biogeochemical processes in the oxygen minimum zone of the eastern South Pacific off Peru, one of the largest low oxygen regions of the world ocean. The researchers focused on so-called marine snow particles of different sizes, which are composed of algal debris and other organic material, aiming to understand how these particles affect the nitrogen cycle in the oxygen minimum zone. Thereby, they solved ...

Women carrying human papillomavirus (HPV) run an elevated risk of preterm birth, a University of Gothenburg study shows. A connection can thus be seen between the virus itself and the risk for preterm birth that previously has been observed in pregnant women who have undergone treatment for abnormal cell changes due to HPV.

A Swedish study now published in the high-ranking journal PLOS Medicine comprises data on more than a million births. Accordingly, the researchers have compared very large groups. They emphasize that the findings do not support any assessment of risk ...

In a study that will be published in Nature Communications on May 28, 2021, a research team led by Dr. Yuan Liu from Georgia State University reports that intratumoral SIRPα-deficient macrophages activate tumor antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells to eliminate various syngeneic cancers under radiotherapy.

As a major component of the suppressive tumor microenvironment, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are generally regarded as facilitators of tumor progression. It has been shown that depleting TAMs can enhance the response of tumors to radiotherapy (RT). However, Yuan's ...

The average IQ of adults born very preterm or very low birth weight was compared to those who were term born in the 1970s to 1990s in 8 longitudinal cohorts from 7 countries around the world

The IQ was significantly lower for very pre-term and very low birth weight adults in comparison to those term born, researchers from the University of Warwick have found

Action needs to be taken to ensure support is available for those born very preterm or very low birth weight

The average IQ of adults who were born very preterm (VP) or at a very low birth weight (VLBW) has been compared to adults born full term by researchers from the Department of Psychology at the University of Warwick. Researchers have found VP/VLBW children may require special ...

A new extensive genetic resource of rat-infecting malaria parasites may help advance the development of malaria prevention and treatment strategies. This trove of genome and phenome information has been published1 by a team of KAUST researchers, along with colleagues in Japan, and the datasets have been made publicly available for malaria researchers.

Rodent malaria parasites are closely related to human parasites but are easier to study because they can be grown in laboratory mice. "Investigations on rodent malaria parasites have played a key role in revealing many aspects of fascinating biology across ...

It is time for the management and conservation of the Antarctic to begin focusing on responsibility, rather than rights, through an Indigenous Māori framework, a University of Otago academic argues.

In an article published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, Associate Professor Priscilla Wehi, of the Centre for Sustainability, says now is the time to be thinking of these potential changes.

"New Zealand is currently re-setting its priorities for future Antarctic research, and there may be review of the current international environmental conventions as we approach the 50-year anniversary of the protocols in 2048.

"We argue that Indigenous Māori frameworks offer powerful ways of thinking about how we protect the Antarctic, by focusing on ...

Invasive species, beware: Your days of hiding may be ending.

Biologists led by the University of Iowa discovered the presence of the invasive New Zealand mud snail by detecting their DNA in waters they were inhabiting incognito. The researchers employed a technique called environmental DNA (eDNA) to reveal the snails' existence, showing the method can be used to detect and control new, unknown incursions by the snail and other invasive species.

"eDNA has been used successfully with other aquatic organisms, but this is the first time it's been applied to detect a new invasive population of these snails, which are a destructive invasive species in fresh waters around the world," says Maurine Neiman, associate professor in the Department ...

How old is your brain compared to your chronological age? A new measure of brain health developed by researchers at Rush University Medical Center may offer a novel approach to identifying individuals at risk of memory and thinking problems, according to research results published in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association on June 1.

Dubbed the "cognitive clock" by the researchers, the tool is a measure of brain health based on cognitive performance. It may be used in the future to predict the likelihood of memory and thinking problems that develop ...

Rare disease experts detail the first results of an unprecedented collaboration to diagnose people living with unsolved cases of rare diseases across Europe. The findings are published today in a series of six papers in the European Journal of Human Genetics.

In the main publication, an international consortium, known as Solve-RD, explains how the periodic reanalysis of genomic and phenotypic information from people living with a rare disease can boost the chance of diagnosis when combined with data sharing across European borders on a massive scale. Using this new approach, a preliminary reanalysis of data from 8,393 individuals resulted in 255 new diagnoses, some with atypical manifestations of known diseases.

A complementary study ...

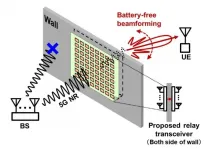

Scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) have developed a wirelessly powered relay network for 5G systems. The proposed battery-free communication addresses the challenges of flexible deployment of relay networks. This design is both economical and energy-efficient. Such advances in 5G communications will create tremendous opportunities for a wide range of sectors.

The ever-increasing demand for wireless data bandwidth shows no sign of slowing down in the near future. Millimeter wave, a short wavelength spectrum, has shown great potential in 5G communications and beyond. To leverage ...