(Press-News.org) Doctors have hoped that antibiotics could benefit patients with chronic lung diseases, but a new study has found no benefit for patients with life-threatening idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in preventing hospitalization or death.

While there were no statistical benefits for patients with the lung-scarring disease, the new research will prevent unnecessary antibiotic use that could contribute to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. The nationwide clinical trial - believed to be the largest idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis trial ever conducted - also collected biological samples that will advance the understanding and treatment of the mysterious and ultimately fatal illness.

"We were certainly disappointed in the results. But we remain hopeful that in further downstream analyses, we may yet find groups of patients that were potentially benefiting. In the meantime, this study will make sure that no one takes antibiotics without need," said researcher Imre Noth, MD, the chief of UVA Health's Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. "We did view the study as great success as an NIH [National Institutes of Health] initiative, in that the pragmatic design, without blinding patients to treatment, led to rapid enrollment, ahead of schedule and basically ahead of budget, showing that large studies can be accomplished in this uncommon disease."

About Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, scar tissue builds up in the lungs over time, preventing them from supplying adequate oxygen to the body. It typically affects people over age 50, mostly men. Patients typically survive only two to five years after diagnosis, though some live much longer.

Doctors are uncertain what triggers idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ("Idiopathic" means "unknown cause.") However, environmental and genetic factors may play a part, as may lung infections.

Doctors also suspect that changes in the microorganisms that naturally live in our lungs may be a factor. Scientists have increasingly come to appreciate the importance of the tiny organisms that live in our bodies and on our skin. In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the thinking goes, the natural state of the microorganisms in the lungs may become unbalanced - perhaps there are too many of one type or a general loss of variety. Lab work in mice has suggested that antimicrobials may be able to help fix the problem.

To see if antimicrobial treatments could benefit idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, researchers at 35 sites around the country conducted a randomized clinical trial with volunteers age 40 or older. A total of 513 patients enrolled between August 2017 and June 2019. Half received antimicrobial drugs, choosing between co-trimoxazol or doxycycline, while the other half received the standard care.

After a median follow-up time of 12.7 months, there was no statistically significant benefit from the antimicrobials. The time to both breathing-related hospitalization or death was unchanged.

The findings echoed those of a previous study, and the researchers say the results show that treatment with antibiotics is ineffective and unwarranted as a general treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. They do not rule out, however, that it may be useful in a limited number of patients with known disruptions to their lung microorganisms.

"As the largest single study in IPF ever conducted, I think we are going to learn a lot as we look at things more closely. Might our choice of antibiotics have been the right ones? Were there some patients that did better than others? Who should we be targeting for treatment? All things this study will help in the future," said Noth, a top expert on the disease. "I am heartened and hopeful moving forward as this study teaches us a lot for the next one, and each study gets us closer to better treatments and a cure."

INFORMATION:

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The research team consisted of Fernando J. Martinez, Eric Yow, Kevin R. Flaherty, Laurie D. Snyder, Michael T. Durheim, Stephen R. Wisniewski, Frank C. Sciurba, Ganesh Raghu, Maria M. Brooks, Dong-Yun Kim, Daniel F. Dilling, Gerard J. Criner, Hyun Kim, Elizabeth A. Belloli, Anoop M. Nambiar, Mary Beth Scholand, Kevin J. Anstrom and Noth for the CleanUP-IPF Investigators of the Pulmonary Trials Cooperative.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health's National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, grant U01HL128964; Three Lakes Foundation; IPF Foundation; and Veracyte Inc. Noth has received funding from NIH, Veracyte and Three Lakes; personal fees from Boerhinger Ingelheim, Genentech and Confo; and has filed for a patent related to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A full list of the authors' disclosures is included in the paper.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at http://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

(Carlisle, Pa.) -- A new study published in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine finds critical links between job loss and physical inactivity in young adults during the U.S. Great Recession of 2008-09 that can be crucial to understanding the role of adverse economic shocks on physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is the first study to examine how job losses during the Great Recession affected the physical activity of young adults in the United States.

The study by Dickinson College economist Shamma Alam and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health economist Bijetri Bose looked at Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) data for young adults age 18 to 27--a phase of development associated with maturation and significant ...

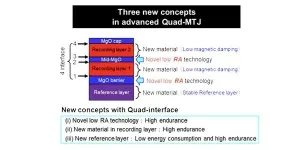

Professor Tetsuo Endoh's Group at Tohoku University's Center for Innovative Integrated Electronics has announced a new magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ) quad-technology that provides better endurance and reliable data retention - over 10 years - beyond the 1X nm generation.

This novel Quad technology meets the design requirements for the state-of-the-art X nm complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) node and will pave the way for ultra-low-power consumption for Internet of Things (IoT) edge-devices in mobile communication, the automotive industry, consumer electronics, ...

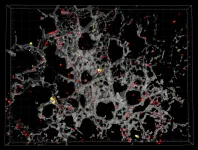

Researchers from Telethon Kids Institute and Curtin University in Perth and Tulane University in New Orleans have developed sophisticated data modelling that could help eradicate malaria in Haiti.

Haiti is the poorest country in the Caribbean - beset by natural disasters - and is one of the few countries in the region that have not mostly wiped out the mosquito-borne disease.

Telethon Kids Institute researcher Associate Professor Ewan Cameron led the team, using a range of different health data to create a complete picture of where malaria infections are taking place in Haiti. This information has been used to directly inform Haiti's national response to malaria.

The team's findings ...

Treating patients with acute respiratory failure is a constant challenge in intensive care medicine. In most cases, the underlying cause is lung inflammation triggered by a bacterial infection or - more rarely, despite being frequently observed at present due to the corona pandemic - a viral infection. During the inflammation, cells of the immune system - the white blood cells - migrate to the lungs and fight the pathogens. At the same time, however, they also cause "collateral damage" in the lung tissue. If the inflammatory reaction is not resolved in time, this can result in chronic inflammation with permanent impairment of lung function. Together with colleagues from London, Madrid and Munich, a research team at the University ...

Researchers at the University of Eastern Finland have uncovered potential mechanisms by which microRNAs (miRNA) drive atherogenesis in a cell-type-specific manner. Published in the Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology journal, the study provides novel insight into the miRNA profiles of the main cell types involved in atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis is the underlying cause of most cardiovascular diseases and one of the leading causes of mortality in the world. During atherosclerosis, arteries become progressively narrow and thick due to the formation of plaques containing cholesterol deposits, calcium and cells, among other components. ...

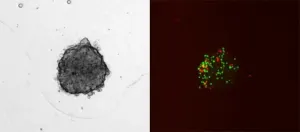

Every tumour is different, every patient is different. So how do we know which treatment will work best for the patient and eradicate the cancer? In order to offer a personalised treatment that best suits the case being treated, a team of scientists led by the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, had already developed a spheroidal reproduction of tumours that integrates the tumour cells, but also their microenvironment. However, the immune system had not yet been taken into account, even though it can either be strengthened or destroyed by the treatment given to the patient. Today, the Geneva team has succeeded in integrating two types of immune cells that come directly from the patient into the spheroidal structure, ...

The Permian Basin, located in western Texas and southeastern New Mexico, is the largest oil- and gas-producing region in the U.S. The oilfield operations emit methane, but quantifying the greenhouse gas is difficult because of the large area and the fact that many sources are intermittent emitters. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Environmental Science & Technology Letters have conducted an extensive airborne campaign with imaging spectrometers and identified large methane sources across this area.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, 38% of the nation's total oil and 17% of natural gas production took place in the Permian Basin in 2020. Therefore, quantifying emissions from these operations, which continue to expand rapidly, is ...

A healthy diet around the time of conception through the second trimester may reduce the risk of several common pregnancy complications, suggests a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health. Expectant women in the study who scored high on any of three measures of healthy eating had lower risks for gestational diabetes, pregnancy-related blood pressure disorders and preterm birth. The study was conducted by Cuilin Zhang, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues at NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). It appears in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. ...

A team of students working with Jonathan Boreyko, associate professor in mechanical engineering at Virginia Tech, has discovered the method ducks use to suspend water in their feathers while diving, allowing them to shake it out when surfacing. The discovery opens the door for applications in marine technology. Findings were published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Boreyko has a well-established body of work in the area of fluid mechanics, including the invention of a fog harp and the use of contained, recirculated steam as a cooling device. As his research has progressed throughout the past decade, the mechanics of duck de-wetting has been one of his longest-running projects.

"I got this idea when I was at Duke University," ...

Jack Tseng loves bone-crunching animals -- hyenas are his favorite -- so when paleontologist Joseph Peterson discovered fossilized dinosaur bones that had teeth marks from a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex, Tseng decided to try to replicate the bite marks and measure how hard those kids could actually chomp down.

Last year, he and Peterson made a metal replica of a scimitar-shaped tooth of a 13-year-old juvie T. rex, mounted it on a mechanical testing frame commonly used in engineering and materials science, and tried to crack a cow legbone with it.

Based on 17 successful attempts to match the depth and shape of the bite marks on the fossils -- he had to toss out some trials because the fresh bone slid around too much -- he determined that a juvenile could have exerted ...