Juvenile white-tailed sea eagles stay longer in the parental territory than assumed

Nest protection periods in Germany are not sufficient and need to be extended

2021-06-02

(Press-News.org) The white-tailed sea eagle is known for reacting sensitively to human disturbances. Forestry and agricultural activities are therefore restricted in the immediate vicinity of the nests. However, these seasonal protection periods are too short in the German federal States of Brandenburg (until August 31) and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (until July 31), as a new scientific analysis by a team of scientists from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) suggests. Using detailed movement data of 24 juvenile white-tailed sea eagles with GPS transmitters, they were able to track when they fledge and when they leave the parental territory: on average, a good 10 and 23 weeks after hatching, respectively. When forestry work is allowed again, most of the young birds are still near the nest. In a publication in the journal IBIS - International Journal of Avian Science, the scientists therefore recommend an extension of the currently existing nest protection periods by one month.

Between 2004 and 2016, bird of prey specialist Dr Oliver Krone and his team from the Leibniz-IZW fitted a total of 24 juvenile white-tailed eagles with GPS transmitters during ringing, which usually takes place between four and six weeks after hatching. The aim was to precisely record and analyse the movements of the younglings in the important life span between the first flight and leaving the parents' territory. "On average, the juvenile white-tailed sea eagles leave the nest for the first time at the age of 72 days for their maiden flight and, on average, leave their parental territory another 93 days later," Krone summarises. During this period, the juvenile birds are very active and undertake frequent excursions from the nest, which vary greatly in length and distance. However, the activity in this phase varies greatly from bird to bird and influences the time of departure from the parental territory. "The more frequently a young eagle makes such reconnaissance flights, the later it leaves the territory for good," explains biologist Marc Engler. The same applies to the quality of this territory: if it offers at least one body of water that is suitable for foraging, the young birds stay with their parents almost four weeks longer.

Both correlations strongly suggest that juvenile white-tailed sea eagles stay as long as possible in the parental territories, provided the conditions are favourable. "If there is more disturbance at a nest, the possibilities of reconnaissance flights for the young eagles are limited and they seem to be forced to disperse earlier," Krone and Engler conclude. On average, they fledge between the end of May and the beginning of July, so the period until dispersal often extends into September or October. "An extension of the nest protection periods of at least one month is therefore advisable in order to avoid disturbances of juvenile eagles in the nest area and thus prevent early dispersal with possible negative effects on their survival. This applies in particular to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, where forestry work and hunting around the white-tailed sea eagle nests can be resumed starting with the beginning of August - when almost two thirds of the younglings still have their centre of life in the parental nest."

Intensive protection efforts over the last 100 years have saved the sea eagle from extinction in Germany. They were placed under protection in the 1920s, after hunting in particular had reduced the population to a critical level. Meanwhile the population of white-tailed sea eagles has grown back to a stable level. Currently there are about 950 breeding pairs of the white-tailed sea eagle in Germany, projections assume a potential of 1200 breeding pairs for Germany. However, the use of leaded ammunition in hunting still has a negative effect on the birds, which in winter feed on the carcasses of animals left behind by hunters. In addition, a team led by Oliver Krone showed that not only forestry work is a burden for the white-tailed sea eagles, but also the proximity to roads especially paths with pedestrians and cyclists. The team measured concentrations of the hormone corticosterone and its metabolic products in white-tailed sea eagles in northern Germany and correlated these values with potential causes of "stress". They found that the levels of corticosterone in the birds' urine are higher the closer a breeding pair's nest is to trails, paths or roads. This paper was published in October 2019 in the scientific journal ""General and Comparative Endocrinology".

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-02

Materials have a variety of properties that can be used to solve computational problems, according to studies in substrate-based computing. BZ computers, slime mould computers, plant computers, and collision-based liquid marbles computers are just a few examples of prototypes produced for future and emergent computing devices. Modelling the computational processes that exist in such systems, however, is a difficult task in general, and determining which part of the embodied system is doing the computation is still somewhat ill-defined.

Claiming that fungi are the most intelligent living organisms in the world sounds like an exaggeration. However, a recent study by Mohammad Mahdi Dehshibi, a UOC researcher who is contributing to a growing body of knowledge on the use of fungal materials, ...

2021-06-02

Eating at least two serves of fruit daily has been linked with 36 percent lower odds of developing type 2 diabetes, a new Edith Cowan University (ECU) study has found.

The study, published today in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, revealed that people who ate at least two serves of fruit per day had higher measures of insulin sensitivity than those who ate less than half a serve.

Type 2 diabetes is a growing public health concern with an estimated 451 million people worldwide living with the condition. A further 374 million people are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

The study's lead author, Dr Nicola ...

2021-06-02

Researchers at Linköping University in Sweden have developed an app to help women achieve a healthy weight gain and lifestyle during a pregnancy. The results from an evaluation of the app have now been published in two scientific articles. Using the app contributed to a better diet. Pregnant women with overweight or obesity who received the app also gained less weight during pregnancy.

"Pregnancy is a phase in life when many people try to do what is best for themselves and their baby. We think it's important to be able to offer a tool that has ...

2021-06-02

Good acoustics in the workspace improve work efficiency and productivity, which is one of the reasons why acoustic materials matter. The acoustic insulation market is already expected to hit 15 billion USD by 2022 as construction firms and industry pay more attention to sound environments. Researchers at Aalto University, in collaboration with Finnish acoustics company Lumir, have now studied how these common elements around us could become more eco-friendly, with the help of cellulose fibres.

'Models for acoustic absorption are based on tests done with synthetic fibres, and ...

2021-06-02

An international research team determined that ancestors of modern domestic horses and the Przewalski horse moved from the territory of Eurasia (Russian Urals, Siberia, Chukotka, and eastern China) to North America (Yukon, Alaska, continental USA) from one continent on another at least twice. It happened during the Late Pleistocene (2.5 million years ago - 11.7 thousand years ago). The analysis results are published in the journal. The findings and description of horse genomes are published in the journal Molecular Ecology.

"We found out that the Beringian Land Bridge, or the area known as Beringia, influenced genetic ...

2021-06-02

All the cells of an organism share the same DNA sequence, but their functions, shapes or even lifespans vary greatly. This happens because each cell "reads" different chapters of the genome, thus producing alternative sets of proteins and embarking on different paths. Epigenetic regulation--DNA methylation is one of the most common mechanisms--is responsible for the activation or inactivation of a given gene in a specific cell, defining a secondary cell-specific genetic code.

Researchers led by Dr. Modesto Orozco, head of the Molecular Modelling and Bioinformatics lab at IRB Barcelona, have described how methylation has a protein-independent regulatory role by increasing the stiffness of DNA, which affects the 3D structure ...

2021-06-02

Autistic people's ability to accurately identify facial expressions is affected by the speed at which the expression is produced and its intensity, according to new research at the University of Birmingham.

In particular, autistic people tend to be less able to accurately identify anger from facial expressions produced at a normal 'real world' speed. The researchers also found that for people with a related disorder, alexithymia, all expressions appeared more intensely emotional.

The question of how people with autism recognise and relate to emotional expression has been debated by scientists for more than three decades and it's only in the past 10 years ...

2021-06-02

The gut and the brain communicate with each other in order to adapt satiety and blood sugar levels during food consumption. The vagus nerve is an important communicator between these two organs. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research in Cologne, the Cluster of Excellence for Ageing Research CECAD at the University of Cologne and the University Hospital Cologne now took a closer look at the functions of the different nerve cells in the control centre of the vagus nerve, and discovered something very surprising: although the nerve cells are located in the same control center, they innervate different regions of the gut and also differentially control satiety and blood sugar levels. This discovery could play an important role in the development of future ...

2021-06-02

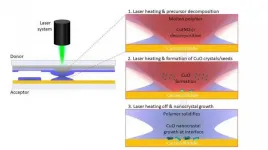

In the journal Nature Communications, an interdisciplinary team from the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces presents for the first time a laser-driven technology that enables them to create nanoparticles such as copper, cobalt and nickel oxides. At the usual printing speed, photoelectrodes are produced in this way, for example, for a wide range of applications such as the generation of green hydrogen.

Previous methods produce such nanomaterials only with high energy input in classical reaction vessels and in many hours. With the laser-driven technology developed at the institute, the scientists can deposit small amounts of material on a surface and simultaneously perform chemical synthesis in a very short time using high temperatures from the laser. 'When I discovered ...

2021-06-02

A facial expression or the sound of a voice can say a lot about a person's emotional state; and how much they reveal depends on the intensity of the feeling. But is it really true that the stronger an emotion, the more intelligible it is? An international research team comprised of scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, New York University, and the Max Planck NYU Center for Language, Music, and Emotion (CLaME) has now discovered a paradoxical relationship between the intensity of emotional expressions and how they are perceived.

Emotions ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Juvenile white-tailed sea eagles stay longer in the parental territory than assumed

Nest protection periods in Germany are not sufficient and need to be extended