UMaine researchers: Culture drives human evolution more than genetics

2021-06-02

(Press-News.org) In a new study, University of Maine researchers found that culture helps humans adapt to their environment and overcome challenges better and faster than genetics.

After conducting an extensive review of the literature and evidence of long-term human evolution, scientists Tim Waring and Zach Wood concluded that humans are experiencing a "special evolutionary transition" in which the importance of culture, such as learned knowledge, practices and skills, is surpassing the value of genes as the primary driver of human evolution.

Culture is an under-appreciated factor in human evolution, Waring says. Like genes, culture helps people adjust to their environment and meet the challenges of survival and reproduction. Culture, however, does so more effectively than genes because the transfer of knowledge is faster and more flexible than the inheritance of genes, according to Waring and Wood.

Culture is a stronger mechanism of adaptation for a couple of reasons, Waring says. It's faster: gene transfer occurs only once a generation, while cultural practices can be rapidly learned and frequently updated. Culture is also more flexible than genes: gene transfer is rigid and limited to the genetic information of two parents, while cultural transmission is based on flexible human learning and effectively unlimited with the ability to make use of information from peers and experts far beyond parents. As a result, cultural evolution is a stronger type of adaptation than old genetics.

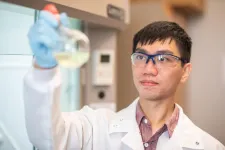

Waring, an associate professor of social-ecological systems modeling, and Wood, a postdoctoral research associate with the School of Biology and Ecology, have just published their findings in a literature review in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the flagship biological research journal of The Royal Society in London.

"This research explains why humans are such a unique species. We evolve both genetically and culturally over time, but we are slowly becoming ever more cultural and ever less genetic," Waring says.

Culture has influenced how humans survive and evolve for millenia. According to Waring and Wood, the combination of both culture and genes has fueled several key adaptations in humans such as reduced aggression, cooperative inclinations, collaborative abilities and the capacity for social learning. Increasingly, the researchers suggest, human adaptations are steered by culture, and require genes to accommodate.

Waring and Wood say culture is also special in one important way: it is strongly group-oriented. Factors like conformity, social identity and shared norms and institutions -- factors that have no genetic equivalent -- make cultural evolution very group-oriented, according to researchers. Therefore, competition between culturally organized groups propels adaptations such as new cooperative norms and social systems that help groups survive better together.

According to researchers, "culturally organized groups appear to solve adaptive problems more readily than individuals, through the compounding value of social learning and cultural transmission in groups." Cultural adaptations may also occur faster in larger groups than in small ones.

With groups primarily driving culture and culture now fueling human evolution more than genetics, Waring and Wood found that evolution itself has become more group-oriented.

"In the very long term, we suggest that humans are evolving from individual genetic organisms to cultural groups which function as superorganisms, similar to ant colonies and beehives," Waring says. "The 'society as organism' metaphor is not so metaphorical after all. This insight can help society better understand how individuals can fit into a well-organized and mutually beneficial system. Take the coronavirus pandemic, for example. An effective national epidemic response program is truly a national immune system, and we can therefore learn directly from how immune systems work to improve our COVID response."

INFORMATION:

Waring is a member of the Cultural Evolution Society, an international research network that studies the evolution of culture in all species. He applies cultural evolution to the study of sustainability in social-ecological systems and cooperation in organizational evolution.

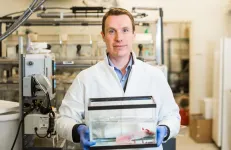

Wood works in the UMaine Evolutionary Applications Laboratory managed by Michael Kinnison, a professor of evolutionary applications. His research focuses on eco-evolutionary dynamics, particularly rapid evolution during trophic cascades.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-02

Icebergs crumbling into the sea may be what first come to mind when imagining the most dramatic effects of global warming.

But new University of Arizona-led research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, suggests that more record-breaking temperatures will actually occur in the tropics, where there is a large and rapidly growing population.

"People recognize that polar warming is much faster than the mid-latitudes and tropics; that's a fact," said lead study author Xubin Zeng, director of the UArizona Climate Dynamics and Hydrometeorology Center and a professor of atmospheric sciences. "The second fact is that the warming over land is greater than over ...

2021-06-02

People of color are more than twice as likely to die after a traumatic brain injury as white people, according to a new retrospective review from Oregon Health & Science University.

The study published today in the journal Frontiers in Surgery.

In the report, "Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Mortality During Hospitalization for Traumatic Brain Injury: A Call to Action," the researchers analyzed more than a decade of data related to the health outcomes and demographics of thousands of patients treated for traumatic head injuries at OHSU Hospital, one of two Level 1 trauma centers in the state.

They found a clear delineation of worse outcomes for people of color.

"We have a societal and professional duty to recognize and accept that the effects of structural ...

2021-06-02

Hydrogels are commonly used inside the body to help in tissue regeneration and drug delivery. However, once inside, they can be challenging to control for optimal use. A team of researchers in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Texas A&M University is developing a new way to manipulate the gel -- by using light.

Graduate student Patrick Lee and Dr. Akhilesh Gaharwar, associate professor, are developing a new class of hydrogels that can leverage light in a multitude of ways. Light is a particularly attractive source of energy as it can be confined to a predefined area as well as be finetuned by the time or intensity of light exposure. Their work was recently published in the journal Advanced Materials.

Light?responsive hydrogels are an ...

2021-06-02

OAKLAND, Calif. -- In patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes, the use of continuous glucose monitors is associated with better blood sugar control and fewer visits to the emergency room for hypoglycemia, a Kaiser Permanente study published June 2 in the journal JAMA found.

The monitors have previously been shown to improve glucose control for patients with type 1 diabetes. Continuous glucose monitors are now the standard of care for these patients.

"The improvement in blood sugar control was comparable to what a patient might experience after starting a new diabetes medication," said the study's lead author Andrew J. Karter, PhD, a senior research scientist with the Kaiser Permanente Northern California ...

2021-06-02

What The Study Did: Researchers investigated the effect of real-time continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control among patients with insulin-treated diabetes.

Authors: Andrew J. Karter, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6530)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study and editorial ...

2021-06-02

BAR HARBOR, MAINE — Many salamanders can readily regenerate a lost limb, but adult mammals, including humans, cannot. Why this is the case is a scientific mystery that has fascinated observers of the natural world for thousands of years.

Now, a team of scientists led by James Godwin, Ph.D., of the MDI Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, has come a step closer to unraveling that mystery with the discovery of differences in molecular signaling that promote regeneration in the axolotl, a highly regenerative salamander, while blocking it in the adult mouse, which is a mammal with limited regenerative ability.

"Scientists at ...

2021-06-02

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University's Computational Biology Department in the School of Computer Science have developed a new process that could reinvigorate the search for natural product drugs to treat cancers, viral infections and other ailments.

The machine learning algorithms developed by the Metabolomics and Metagenomics Lab match the signals of a microbe's metabolites with its genomic signals and identify which likely correspond to a natural product. Knowing that, researchers are better equipped to isolate the natural product to begin developing it for a possible drug.

"Natural products are still one of the most successful paths for drug discovery," said Bahar Behsaz, a project scientist in the lab and lead author of a paper about the process. "And ...

2021-06-02

A team of Colorado State University scientists, led by veterinary postdoctoral fellow Dr. Anna Fagre, has detected Zika virus RNA in free-ranging African bats. RNA, or ribonucleic acid, is a molecule that plays a central role in the function of genes.

According to Fagre, the new research is a first-ever in science. It also marks the first time scientists have published a study on the detection of Zika virus RNA in any free-ranging bat.

The findings have ecological implications and raise questions about how bats are exposed to Zika virus in nature. The study was recently published in Scientific Reports, a journal published by Nature Research.

Fagre, a researcher at CSU's Center for Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, ...

2021-06-02

ITHACA, N.Y. - All fish are not created equal, at least when it comes to nutritional benefits.

This truth has important implications for how declining fish biodiversity can affect human nutrition, according to a computer modeling study led by Cornell and Columbia University researchers.

The study, "Declining Diversity of Wild-Caught Species Puts Dietary Nutrient Supplies at Risk," published May 28 in Science Advances, focused on the Loreto region of the Peruvian Amazon, where inland fisheries provide a critical source of nutrition for the 800,000 inhabitants.

At the same time, the findings apply to fish biodiversity worldwide, as more than 2 billion people depend on fish as their primary source of animal-derived nutrients.

"Investing in safeguarding biodiversity can deliver ...

2021-06-02

Researchers at Kyoto University's Institute for Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS) have developed a new approach to speed up hydrogen atoms moving through a crystal lattice structure at lower temperatures. They reported their findings in the journal Science Advances.

"Improving hydrogen transport in solids could lead to more sustainable sources of energy," says Hiroshi Kageyama of iCeMS who led the study.

Negatively charged hydrogen 'anions' can move very quickly through a solid 'hydride' material, which consists of hydrogen atoms attached to other chemical elements. This system is a promising contender for clean energy, but the fast ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] UMaine researchers: Culture drives human evolution more than genetics