(Press-News.org) A new study from the University of Chicago and Scripps Research Institute shows that during the last great pandemic--2009's H1N1 influenza pandemic--people developed strong, effective immune responses to stable, conserved parts of the virus. This suggests a strategy for developing universal flu vaccines that are designed to generate those same responses, instead of targeting parts of the virus that tend to evolve rapidly and require a new vaccine every year.

Influenza is an elusive and frustrating target for vaccines. There are two main types of flu virus that can infect humans, which evolve rapidly from season to season. When developing seasonal flu vaccines, health officials try to anticipate the predominant variation of the virus that will circulate that year. These predictions are often slightly off. Sometimes new, unexpected variants emerge, which means the vaccine may not be very effective. To avoid this, the ultimate goal of many flu researchers is to develop a universal vaccine that can account for any virus strain or variation in a given year, or even longer.

The new study, published June 2 in Science Translational Medicine, was led by UChicago immunologists Jenna Guthmiller, PhD, and Patrick Wilson, PhD, along with structural biologists Julianna Han, PhD, and Andrew Ward, PhD, from Scripps Research Institute. They studied the immune responses of people who were first exposed to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic flu virus, either from infection or a vaccine.

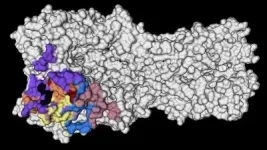

The researchers saw that the immune systems of these people recalled memory B cells from their childhood that produced broadly neutralizing antibodies against highly conserved parts on the head of a protein called hemagglutinin (HA) -- a virus surface protein that attaches to receptors on host cells. These antibody responses were very effective at combatting the virus, and because they targeted conserved parts of the HA protein--meaning they don't change very often--they could provide an enticing target for a vaccine to generate those same robust immune responses.

In a separate 2020 study, Guthmiller and colleagues found so-called polyreactive antibodies that can bind to several conserved sites on the flu virus. Now, the new study reveals more details about the conditions that can recall the same strong immune responses as this first exposure.

"That's the exciting thing about this study," Guthmilller said. "Not only have we found these broadly neutralizing antibodies, but now we know of a way to actually induce them."

The only problem is that on subsequent encounters with the virus or a vaccine, the body doesn't generate those same super-effective antibodies. Instead, for reasons that are unclear, the immune system tends to target newer variations on the virus. That may be effective at the time, but isn't very helpful down the road when another, slightly different version of influenza comes along.

"When people encounter that virus a second or third time, their antibody response is pretty much completely dominated by antibodies against those more variable parts of the virus," Guthmiller said. "So that's the uphill battle that we continue to face with this."

The trick to getting around this is to design a vaccine that recreates that initial encounter with H1N1, using a version of the HA protein that keeps the conserved, powerful antibody-inducing components, and replaces the variable parts with other molecules that won't distract the immune system.

"Structural studies were essential to delineate the conserved areas on the HA protein," said Han, who was co-first author of the new study and received her doctorate from the Committee on Microbiology at UChicago. "Now these data can be used to fine-tune vaccine targets."

In roughly the past century, two of the four flu pandemics have been caused by H1N1 influenza, including the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic that killed as many as 100 million people. Yet the findings of this study are reassuring in the fight against possible future pandemics caused by other H1 viruses.

"The odds of there being another pandemic within our lifetime caused by an H1 virus is quite high," Guthmiller said. "Just knowing that we actually have the immune toolkit ready to protect ourselves is encouraging. Now it's just a matter of getting the right vaccine to do that."

INFORMATION:

The study, "First exposure to the pandemic H1N1 virus induced broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting hemagglutinin head epitopes," was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and GlaxoSmithKline. Additional authors include Lei Li, Olivia Stovicek, Micah E. Tepora, Henry A. Utset, Dalia J. Bitar, Natalie J. Hamel, Siriruk Changrob, Nai-Ying Zheng, Min Huang, Christopher T. Stamper, and Haley L. Dugan from the University of Chicago; and Alec W. Freyn, Sean T.H. Liu, Florian Krammer, Raffael Nachbagauer, and Peter Palese from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Neurological and psychiatric symptoms such as fatigue and depression are common among people with Covid-19 and may be just as likely in people with mild cases, according to a new review study led by a UCL researcher.

By reviewing evidence from 215 studies of Covid-19, the meta-analysis published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry reports a wide range of ways that Covid-19 can affect mental health and the brain.

Lead author Dr Jonathan Rogers (UCL Psychiatry and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust) said: "We had expected that neurological and psychiatric symptoms would be ...

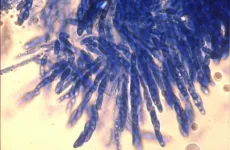

Researchers have re-animated specimens of a fungus that causes coffee wilt to discover how the disease evolved and how its spread can be prevented.

Coffee Wilt Disease is caused by a fungus that has led to devastating outbreaks since the 1920s in sub-Saharan Africa, and currently affects two of Africa's most popular coffee varieties: Arabica and Robusta.

The new research shows that the fungus likely boosted its ability to infect coffee plants by acquiring genes from a closely related fungus, which causes wilt disease on a wide range of crops, including ...

Sea ice in the coastal regions of the Arctic may be thinning up to twice as fast as previously thought, according to a new modelling study led by UCL researchers.

Sea ice thickness is inferred by measuring the height of the ice above the water, and this measurement is distorted by snow weighing the ice floe down. Scientists adjust for this using a map of snow depth in the Arctic that is decades out of date and does not account for climate change.

In the new study, published in the journal The Cryosphere, researchers swapped this map for the results of a new computer model designed to estimate snow depth as it varies year to year, and concluded that sea ice in key ...

Concerns about side effects and whether vaccines have been through enough testing are holding people back from getting vaccinated against COVID-19, according to a new report.

Data from an international survey of 15 countries* which ran between March and May this year showed that these were the most commonly cited reasons for not having had a coronavirus vaccine yet, in addition to not being eligible for one. Respondents' other commonly reported reasons included concerns about not getting the vaccine they would prefer, and worries over whether the vaccines are effective enough.

Led by Imperial College London's Institute of Global Health Innovation in collaboration with YouGov, the survey also looked at trust in COVID-19 vaccines. ...

A University of Birmingham-led study funded by the UK Coronavirus Immunology Consortium has found that many patients with COVID-19 produce immune responses against their body's own tissues or organs.

COVID-19 has been associated with a variety of unexpected symptoms, both at the time of infection and for many months afterwards. It is not fully understand what causes these symptoms, but one of the possibilities is that COVID-19 is triggering an autoimmune process where the immune system is misdirected to attack itself.

The study, published today (June 4) in the journal Clinical & Experimental Immunology, investigated the frequency and types of common ...

Under embargo until Thursday 3 June, 23:30 UK time / 18:30 US Eastern time

Peer-reviewed observational study in people

Prior Covid-19 infection reduces infection risk for up to 10 months

The risk of being infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, is substantially reduced for up to 10 months following a first infection, according to new findings from the Vivaldi study led by UCL researchers.

For the study, published in Lancet Healthy Longevity, researchers looked at rates of Covid-19 infections between October and February among more than 2,000 care home residents and staff, comparing those who had evidence of a previous infection up to 10 months earlier, as determined by antibody testing, with those who had ...

Levels of antibodies in the blood of vaccinated people that are able to recognise and fight the new SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant first discovered in India (B.1.617.2) are on average lower than those against previously circulating variants in the UK, according to new laboratory data from the Francis Crick Institute and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) UCLH Biomedical Research Centre, published today (Thursday) as a Research letter in The Lancet.

The results also show that levels of these antibodies are lower with increasing age and that levels decline over time, providing additional evidence in support of plans to deliver a vaccination boost to vulnerable people in the Autumn. ...

An immunotherapy drug given after surgery improved disease-free survival rates in patients with kidney cancer at high risk of relapse.

Interim results of a phase 3 trial of adjuvant therapy revealed a 32% decrease in the risk of recurrence or death with pembrolizumab compared with a placebo

This is the first positive study of immunotherapy in patients with kidney cancer at high risk of relapse.

BOSTON -- Treatment with an immunotherapy drug following kidney cancer surgery, prolonged disease-free survival rates in patients at high risk for recurrence, according to an interim ...

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common deadly genetic disorder, affecting more than 300,000 newborns worldwide each year. It leads to chronic pain, organ failure, and early death in patients. A team led by researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital has now demonstrated a base editing approach that efficiently corrects the mutation underlying SCD in patient blood stem cells and in mice. This gene editing treatment rescued the disease symptoms in animal models, enabling the long-lasting production of healthy blood cells.

The root of SCD is two mutated copies of the hemoglobin gene, HBB, which cause red ...

After a 2020 Vanderbilt University Medical Center study showed women have a difficult time accessing treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), investigators analyzed comments received from the study's participants to further shed light on barriers to care, which included everything from long on-hold times to difficult interactions with clinic receptionists during phone calls seeking appointments.

A "secret shopper" study published in JAMA Network Open in 2020 used trained actors trying to get into treatment for opioid use disorder in 10 U.S. states. More than 10,000 unique "patients" were randomly assigned to be pregnant or non-pregnant and have private or Medicaid-based insurance to assess differences ...