(Press-News.org) Heart attacks and strokes -- the leading causes of death in human beings -- are fundamentally blood clots of the heart and brain. Better understanding how the blood-clotting process works and how to accelerate or slow down clotting, depending on the medical need, could save lives.

New research by the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University published in the journal Biomaterials sheds new light on the mechanics and physics of blood clotting through modeling the dynamics at play during a still poorly understood phase of blood clotting called clot contraction.

"Blood clotting is actually a physics-based phenomenon that must occur to stem bleeding after an injury," said Wilbur A. Lam, W. Paul Bowers Research Chair in the Department of Pediatrics and the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory. "The biology is known. The biochemistry is known. But how this ultimately translates into physics is an untapped area."

And that's a problem, argues Lam and his research colleagues, since blood clotting is ultimately about "how good of a seal can the body make on this damaged blood vessel to stop bleeding, or when this goes wrong, how does the body accidentally make clots in our heart vessels or in our brain?"

How Blood Clotting Works

The workhorses to stem bleeding are platelets -- tiny 2-micrometer cells in the blood in charge of making the initial plug. The clot that forms is called fibrin, which acts as a glue scaffold that the platelets attach to and pull against. Blood clot contraction arises when these platelets interact with the fibrin scaffold. To demonstrate the contraction, researchers embedded a 3-millimeter Jell-O mold of a LEGO figure with millions of platelets and fibrin to recreate a simplified version of a blood clot.

"What we don't know is, 'How does that work?' 'What's the timing of it so all these cells work together -- do they all pull at the same time?' Those are the fundamental questions that we worked together to answer," Lam said.

Lam's lab collaborated with Georgia Tech's Complex Fluids Modeling and Simulation group headed by Alexander Alexeev, professor and Anderer Faculty Fellow in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, to create a computational model of a contracting clot. The model incorporates fibrin fibers forming a three-dimensional network and distributed platelets that can extend filopodia, or the tentacle-like structures that extend from cells so they can attach to specific surfaces, to pull the nearby fibers.

Model Shows Platelets Dramatically Reducing Clot Volume

When the researchers simulated a clot where a large group of platelets was activated at the same time, the tiny cells could only reach nearby fibrins because the platelets can extend filopodia that are rather short, less than 6 micrometers. "But in a trauma, some platelets contract first. They shrink the clot so the other platelets will see more fibrins nearby, and it effectively increases the clot force," Alexeev explained. Due to the asynchronous platelet activity, the force enhancement can be as high as 70%, leading to a 90% decrease of the clot volume.

"The simulations showed that the platelets work best when they're not in total sync with each other," Lam said. "These platelets are actually pulling at different times and by doing that they're increasing the efficiency (of the clot)."

This phenomenon, dubbed by the team asynchronous mechanical amplification, is most pronounced "when we have the right concentration of the platelets corresponding to that of healthy patients," Alexeev said.

Research Could Lead to Better Ways to Treat Clotting, Bleeding Issues

The findings could open medical options for people with clotting issues, said Lam, who treats young patients with blood disorders as a pediatric hematologist in the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta.

"If we know why this happens, then we have a whole new potential avenue of treatments for diseases of blood clotting," he said, emphasizing that heart attacks and strokes occur when this biophysical process goes wrong.

Lam explained that fine tuning the contraction process to make it faster or more robust could help patients who are bleeding from a car accident or, in the case of a heart attack, make the clotting less intense and slow it down.

"Understanding the physics of this clot contraction could potentially lead to new ways to treat bleeding problems and clotting problems."

Alexeev added that their research also could lead to new biomaterials such as a new type of Band-Aid that could help augment the clotting process.

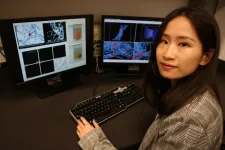

First author and Georgia Tech Ph.D. candidate Yueyi Sun noted the simplicity of the model and the fact that the simulations allowed the team to understand how the platelets work together to contract the fibrin clot as they would in the body.

"When we started to include the heterogeneous activation, suddenly it gave us the correct volume contraction," she said. "Allowing the platelets to have some time delay so one can use what the previous ones did as a better starting point was really neat to see. I think our model can potentially be used to provide guidelines for designing novel active biological and synthetic materials."

Sun agreed with her research colleagues that this phenomenon might occur in other aspects of nature. For example, multiple asynchronous actuators can fold a large net more effectively to enhance packaging efficiency without the need of incorporating additional actuators.

"It theoretically could be an engineered principle," Lam said. "For a wound to shrink more, maybe we don't have the chemical reactions occur at the same time -- maybe we have different chemical reactions occur at different times. You gain better efficiency and contraction when one allows half or all of the platelets to do the work together."

Building on the research, Sun hopes to examine more closely how a single platelet force converts or is transmitted to the clot force, and how much force is needed to hold two sides of a graph together from a thickness and width standpoint. Sun also intends to include red blood cells in their model since they account for 40% of all blood and play a role in defining the clot size.

"If your red blood cells are too easily trapped in your clot, then you are more likely to have a large clot, which causes a thrombosis issue," she explained.

INFORMATION:

CITATION: Y. Sun, et.al., "Platelet heterogeneity enhances blood clot volumetric contraction: An example of asynchrono-mechanical amplification." (Biomaterials 274, 120828, 2021) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120828

The Georgia Institute of Technology, or Georgia Tech, is a top 10 public research university developing leaders who advance technology and improve the human condition.

The Institute offers business, computing, design, engineering, liberal arts, and sciences degrees. Its nearly 40,000 students, representing 50 states and 149 countries, study at the main campus in Atlanta, at campuses in France and China, and through distance and online learning.

As a leading technological university, Georgia Tech is an engine of economic development for Georgia, the Southeast, and the nation, conducting more than $1 billion in research annually for government, industry, and society.

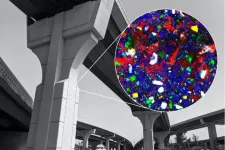

The concrete world that surrounds us owes its shape and durability to chemical reactions that start when ordinary Portland cement is mixed with water. Now, MIT scientists have demonstrated a way to watch these reactions under real-world conditions, an advance that may help researchers find ways to make concrete more sustainable.

The study is a "Brothers Lumière moment for concrete science," says co-author Franz-Josef Ulm, professor of civil and environmental engineering and faculty director of the MIT Concrete Sustainability Hub, referring to the two brothers who ushered in the era of projected films. Likewise, Ulm says, the MIT team has provided a glimpse of early-stage cement hydration that is like cinema in Technicolor ...

A new technology could dramatically improve the safety of lithium-ion batteries that operate with gas electrolytes at ultra-low temperatures. Nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego developed a separator--the part of the battery that serves as a barrier between the anode and cathode--that keeps the gas-based electrolytes in these batteries from vaporizing. This new separator could, in turn, help prevent the buildup of pressure inside the battery that leads to swelling and explosions.

"By trapping gas molecules, this separator can function as a stabilizer for volatile electrolytes," said Zheng Chen, a ...

To describe something as slow and boring we say it's "like watching grass grow", but scientists studying the early morning activity of plants have found they make a rapid start to their day - within minutes of dawn.

Just as sunrise stimulates the dawn chorus of birds, so too does sunrise stimulate a dawn burst of activity in plants.

Early morning is an important time for plants. The arrival of light at the start of the day plays a vital role in coordinating growth processes in plants and is the major cue that keeps the inner clock of plants in rhythm with day-night cycles.

This inner circadian clock helps plants prepare for the day such as when to make the best use of sunlight, the best time to open flowers ...

Citizen opposition to COVID-19 vaccination has emerged across the globe, prompting pushes for mandatory vaccination policies. But a new study based on evidence from Germany and on a model of the dynamic nature of people's resistance to COVID-19 vaccination sounds an alarm: mandating vaccination could have a substantial negative impact on voluntary compliance.

Majorities in many countries now favor mandatory vaccination. In March, the government of Galicia in Spain made vaccinations mandatory for adults, subjecting violators to substantial fines. Italy has made vaccinations mandatory for care workers. The University of California and California State University systems announced in late April that vaccination ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Building lights are a deadly lure for the billions of birds that migrate at night, disrupting their natural navigation cues and leading to deadly collisions. But even if you can't turn out all the lights in a building, darkening even some windows at night during bird migration periods could be a major lifesaver for birds.

Research published this week in PNAS found that over the course of 21 years, one building sustained 11 times fewer nighttime bird collisions during spring migration and 6 times fewer collisions during fall migration when only half of the building's windows were illuminated, compared ...

Many mainstream depictions of immigration at the southern border of the United States paint a dark picture, eliciting imagery of violent gang members and child trafficking. But how many undocumented immigrants are really involved in this kind of activity? Many people may be surprised to learn the answer is far fewer than they think.

A new study from the Peace and Conflict Neuroscience Lab (PCNL) at the Annenberg School for Communication found that Americans dramatically overestimate the number of migrants affiliated with gangs and children being trafficked, and that this overestimation contributes to dehumanization of migrants, lack of empathy for their suffering, and individuals' views on immigration policy. In addition, the researchers developed and tested interventions to ...

Brazilian researchers have simultaneously demonstrated the mechanism linking high blood pressure to elevated intracranial pressure, validated a non-invasive intracranial pressure monitoring method, and proposed a treatment for high blood pressure that does not affect intracranial hypertension.

The study was supported by FAPESP and involved collaboration between researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP) and Brain4care, a startup based in São Carlos. It could result in novel treatments for intracranial hypertension and its complications, including stroke. The main findings are reported in the journal Hypertension.

The researchers monitored blood pressure and intracranial pressure in rats for six weeks. “We set out to investigate ...

Biomolecules regulate the biological functions inside every living cell. If scientists can understand the molecular mechanisms of such functions, then it is possible to detect the severe dysfunction which can lead to illness. At a molecular level, this can be achieved with fluorescent markers that are specifically incorporated into the respective biomolecules. In the past, this has been achieved by incorporating a marker in the bio-molecule by completely rebuilding it from the beginning, necessitating a large number of steps. Unfortunate-ly, this approach not only takes a lot of time and resources, but also produces unwanted waste products. Researchers at the Universities of Göttingen and Edinburgh have now ...

If you're a beer drinker, you've noticed that hoppy beers have become increasingly popular. Most of the nation's hops come from the Pacific Northwest. However, commercial hop production regions have expanded significantly. In Michigan hop production nearly tripled between 2014 and 2017 and in 2019, Michigan growers harvested around 720 acres of hops.

Michigan hop growers contend with unique challenges as a result of frequent rainfall and high humidity during the growing season. In 2018, growers approached Michigan State University researchers and the Michigan State University's Plant & Pest Diagnostics lab with concerns about a leaf blight ...

ORLANDO, June 2021 - A new study co-authored by University of Central Florida researchers shows that pre-Columbian people of a culturally diverse but not well-documented area of the Amazon in South America significantly altered their landscape thousands of years earlier than previously thought.

The findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, show evidence of people using fire and improving their landscape for farming and fishing more than 3,500 years ago. This counters the often-held notion of a pristine Amazon during pre-Columbian times before the arrival of Europeans in the late 1400s.

The study, ...