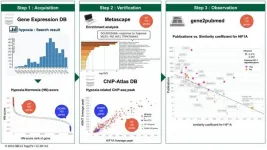

(Press-News.org) Scientists have leapt over the emerging problem of publication bias within genetic research by performing a meta-analysis of publicly available databases of 'transcriptomes', or the full range of messenger RNA molecules produced by an organism. Researchers from Hiroshima University applied the technique to their own field--the study of the genes that are activated when an organism experiences low-oxygen conditions--but it should also be applicable in any other fields that make use of the transcriptome, providing a powerful weapon against the threat posed by publication bias.

The meta-analysis technique was published in a paper appearing in the journal Biomedicines in May 2021.

Scientists are often held up as the pinnacle of objective, disinterested observation and investigation. But in recent years, the danger of what is called publication bias, or sometimes the 'file-drawer problem' is being recognized right across the natural sciences. It describes the bias of researchers and of scientific journals toward the publication of results that support the hypotheses of researchers or otherwise show a significant finding. Both researchers and journals are frequently not very excited about experiments that do not support their hypotheses, and so the findings are left 'in the researcher's file drawer.' There may be no malevolent intention behind such exclusion, but the lack of publication of these 'boring' results does skew, or bias, what exists across the published scientific literature. Ironically, the more well studied the field, the greater the effect of such publication bias.

The Hiroshima University researchers had noticed that there were some 600,000 publications in scientific journals that described around 20,000 human genes that code for the building of a specific protein (as opposed to 'non-coding' genes that perform other functions but do not code for a protein). Across this enormous number of publications, there were a whopping 9,000 articles that discussed the p53 gene, but some 600 genes were not mentioned at all.

Within their own field, they found that this sort of publication bias had led to a great focus on genes that are already well known to be activated during conditions of hypoxia, or low-oxygen conditions.

Under hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, or HIFs, are produced. Transcription factors are proteins that control the rate of transcription (copying a segment of DNA into RNA in order for the RNA to then be translated into a protein). When human cells are deprived of sufficient oxygen, there is a response system governed by the HIFs that attempts to ameliorate the effects of hypoxia by preventing cells from differentiating and by promoting the formation of blood vessels. And HIFs are known to be activated by certain genes.

"But are there other genes that are activated during hypoxia that all researchers have up till now somehow missed due to this publication bias?" asked lead author Hidemasa Bono, professor in the Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life at Hiroshima University.

As transcriptome researchers, Bono and his team knew that, unlike with scientific articles in journals, all transcriptome data have to be archived in public databases, not just the interesting transcriptome data.

"So we thought that if we performed a meta-analysis--or an analysis of analyses--on these transcriptome data, we might be able to identify novel hypoxia-inducible genes that had been buried by publication bias," Bono added.

They searched publicly available transcriptome databases to obtain hypoxia-related experimental data, retrieved the metadata, and then manually curated it. They then selected all the genes that are expressed during hypoxic stimulation, and evaluated their relevance in hypoxia by performing gene enrichment analyses. This latter method allows the statistical identification of groups of genes that are over-represented in a large set of genes, and so may be associated with a particular condition.

Alongside this, the researchers performed a bibliometric analysis, a statistical method of analyzing the occurrence of particular words or phrases commonly used in library and information science. The bibliometric analysis in this case was used on the gene2pubmed--a gene literature data source that describes which genes have been discussed where in the scientific literature--to identify genes that have not been well studied in relation to hypoxia. This is a new type of analysis that within biomedical research is called the 'bibliome'.

By combining the transcriptomic meta-analysis and the bibliome, the researchers were indeed able to find four genes that were not previously known to be associated with hypoxia.

The results have encouraged the researchers to keep going with their meta-analysis technique. They plan to keep using public databases to discover similar new findings, in particular to investigate gene activation (expression) of non-coding RNAs, or RNA molecules that are not translated into proteins, during hypoxic stress.

INFORMATION:

About Hiroshima University

Since its foundation in 1949, Hiroshima University has striven to become one of the most prominent and comprehensive universities in Japan for the promotion and development of scholarship and education. Consisting of 12 schools for undergraduate level and 4 graduate schools, ranging from natural sciences to humanities and social sciences, the university has grown into one of the most distinguished comprehensive research universities in Japan. English website: https://www.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/en

A research collaboration based in Kumamoto University, Japan has revealed the DNA methylation status of gene transcriptional regulatory regions in the frontal lobes of patients with bipolar disorder (BD). The regions with altered DNA methylation status were significantly enriched in genomic regions which were reported to be genetically related to BD. These findings are expected to advance the understanding of the pathogenesis of BD and the development of therapeutic drugs targeting epigenetic conditions.

BD is a mental disorder that affects about 1% of the population and requires long-term treatment. Epidemiological studies have ...

RUDN University chemist with his colleagues from Portugal has developed two types of coating based on new coordination polymers with silver. Both compounds were successfully tested against four common pathogens. The results are published in ACS Publications (ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces).

Due to the rapid mutation, harmful microorganisms constantly adapt to new antibiotics and antiseptics. It is especially difficult to destroy bacteria when they form a biofilm. They stick together and create a community ready to fight antimicrobial agents back. Coordination polymers (scaffolds made of metal ions and organic ligands) can solve this problem. They prevent pathogens from ...

Since energy storage devices are often used in a magnetic field environment, scientists have often explored how an external magnetic field affects the charge storage of nonmagnetic aqueous carbon-based supercapacitor systems.

Recently, an experiment designed by Prof. YAN Xingbin's group from the Lanzhou Institute of Chemical Physics (LICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has revealed that applying an external magnetic field can induce capacitance change in aqueous acidic and alkaline electrolytes, but not in neutral electrolytes. The experiment also shows that the force field can explain the origin of the magnetic field effect.

This new discovery establishes ...

Tokyo, Japan - Incoming sensory information can affect the brain's structure, which may in turn affect the body's motor output. However, the specifics of this process are not always well understood. In a recent study published in Scientific Reports, researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) found that when young rats were fed a diet of either soft or regular food, these different sensory inputs led to differences in muscle control and electrical activity of the jaw when a specific chewing-related brain region was stimulated.

Chewing is mainly controlled by the brainstem, a brain region that controls many automatic activities such as breathing and swallowing. For ...

Indigenous Māori people may have set eyes on Antarctic waters and perhaps the continent as early as the 7th century, new research published in the peer-reviewed Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand shows.

Over the last 200 years, narratives about the Antarctic have been of those carried out by predominantly European male explorers.

However, this new study uncovers the story of the deep-rooted connections of Māori (and Polynesian) people with Antarctica dating back as far as the seventh century and continuing into the present day.

"We found connections to Antarctica and its waters have been occurring since the earliest traditional voyaging, and later ...

RUDN University professor and her colleagues from France proved that higher intake of magnesium and vitamin B6 helps to cope with the consequences of magnesium deficiency during pregnancy and in hormone-related conditions in women. Within four weeks, the painful symptoms become less severe, the quality of life improves, and the risks of miscarriage are reduced. The results of the study are published in Scientific Reports.

Magnesium is involved in important processes in the human body -- from protein synthesis to respiration. The most common causes of magnesium imbalance are a lack of this element in the diet, diabetes, and hypertension. The problem of magnesium ...

The research team led by Prof. GUO Guangcan from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), together with Prof. Adam Gali from Wigner Research Centre for Physics, realized robust coherent control of solid-state spin qubits using anti-Strokes (AS) excitation, broadening the boundary of quantum information processing and quantum sensing. This study was published in Nature Communications.

Solid-state color center spin qubits play an important role in quantum computing, quantum networks and high-sensitivity quantum sensing. Considered as the basis of quantum technology application, optically detected magnetic ...

Research, development, and production of novel materials depend heavily on the availability of fast and at the same time accurate simulation methods. Machine learning, in which artificial intelligence (AI) autonomously acquires and applies new knowledge, will soon enable researchers to develop complex material systems in a purely virtual environment. How does this work, and which applications will benefit? In an article published in the Nature Materials journal, a researcher from Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and his colleagues from Göttingen and Toronto explain it all. (DOI: 10.1038/s41563-020-0777-6)

Digitization and virtualization are becoming increasingly important in a wide range of scientific disciplines. One of these disciplines ...

A research team led by Professor Jianping Huang from Lanzhou University has launched a Global Prediction System for COVID-19 pandemic. Their recent work explored the periodicity and mutability in the evolutionary history of the COVID-19 pandemic and investigated the principle mechanisms behind them. They attributed the periodic oscillations of COVID-19 daily cases to seasonal modulations and reporting bias, and identified the unrestricted mass gatherings as the main culprit of the COVID-19 disaster.

Their findings, entitled "The oscillation-outbreaks characteristic of the COVID-19 pandemic", were published in National Science Review.

In this study, the influence ...

Bristle worms are found almost everywhere in seawater, they have populated the oceans for hundreds of millions of years. Nevertheless, some of their special features have only now been deciphered: Their jaws are made of remarkably stable material, and the secret of this stability can now be explained by experiments at TU Wien in cooperation with Max Perutz Labs.

Metal atoms, which are incorporated into the protein structure of the material, play a decisive role. They make the material hard and flexible at the same time - very similar to ordinary metals. Further ...